New Delhi: “I began to hear the chilling screams of a woman next door”, wrote Moazzem Begg in his memoirs of his time in Afghanistan’s Bagram prison, on terrorism charges that were later dropped. “For two days and nights I heard the sound of the screaming. I felt my mind collapsing…They told me there was no woman. But I was unconvinced. Those screams echoed through my worst nightmares for a long time. And I later learned in Guantanamo, from other prisoners, that they had heard the screams too.”

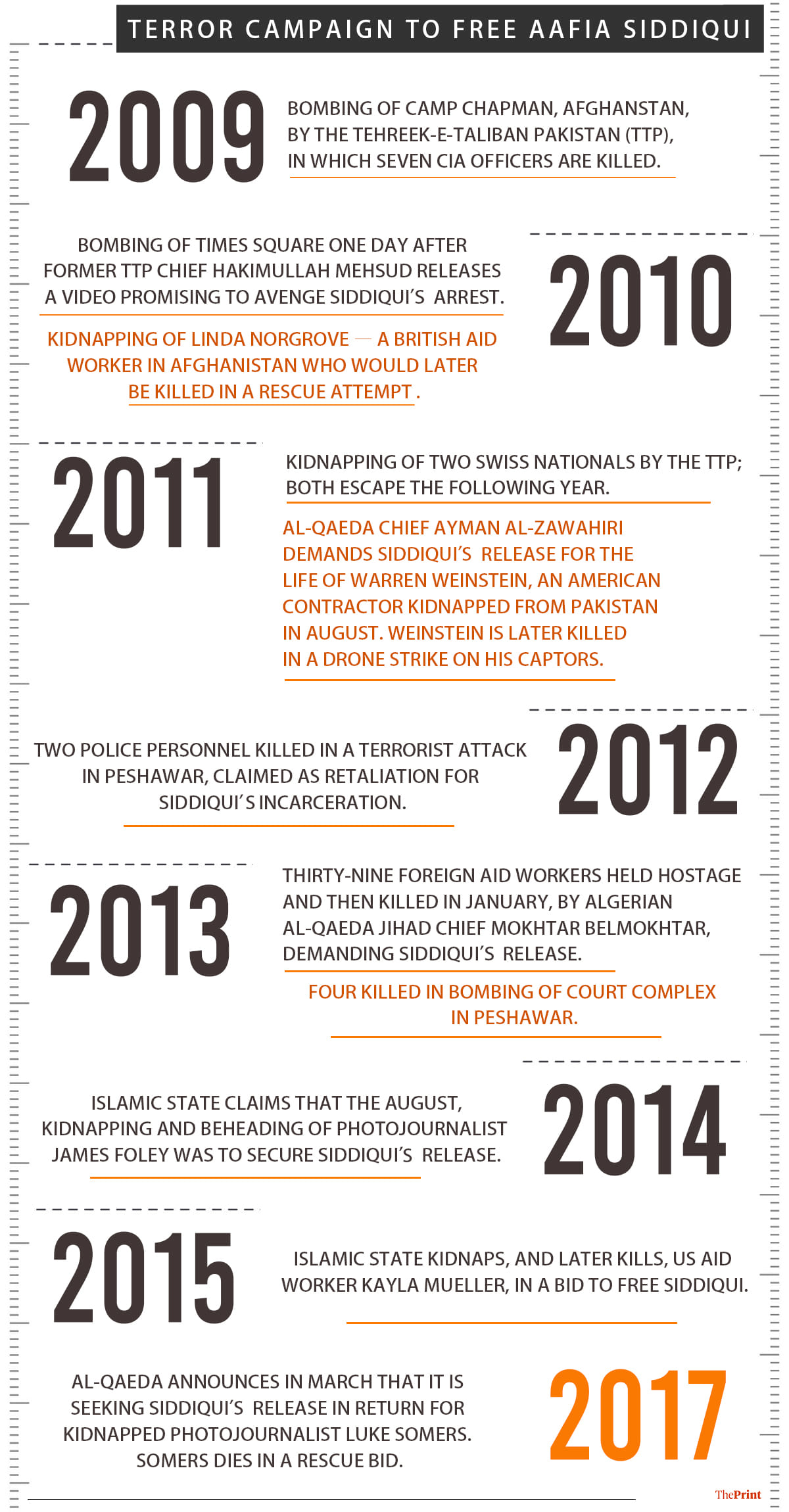

This weekend, 44-year-old British-Pakistani Malik Faisal Akram walked into a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, and took four people hostage in return for the release of Prisoner 650, as others held in Bagram knew the woman. Thus far, at least 57 people have been killed in the jihadi campaign to free Pakistani-American neuroscientist Aafia Siddiqui, or avenge her arrest. (See timeline below)

Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan, various Islamist political parties and jihadist groups have all competed to spearhead the campaign to free Siddiqui, casting it as a struggle for Islam and the honour of Muslim women against a predatory West. Leaders like Khan had perhaps hoped their advocacy of Siddiqui would undermine their enemies, and pluck an arrow out of the jihadis’ quiver. Instead, the synagogue attack suggests, they’ve ended up strengthening the jihadi narrative.

Also read: Pakistani State won’t collapse. Choice is between civil war and short-term rise in violence

How ‘Lady al-Qaeda’ was born

‘Bagram’s Grey Lady’, ’Lady al-Qaeda’, ‘Al-Qaeda’s Mata Hari’: Siddiqui isn’t unique in being a woman jihadi. There’s the Islamic State’s ‘White Widow’, Samantha Lewthwaite, arguably the world’s most wanted woman, and Sally-Anne Jones, targeted in a 2017 drone strike in Syria along with her teenage son. Islamism isn’t the only cause to have drawn women terrorists, either: Think the German communist Ulrike Meinhof, a founding member of the Red Army Faction, or Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s assassin Thenmozhi Rajaratnam.

The daughter of Mohammad Siddiqui, a Karachi doctor, and Ismet, a social worker well connected to General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, Siddiqui moved to the United States in her late teens, in 1990, and went on to study at the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Brandeis University. In 1995, she had an arranged marriage to a Karachi doctor, Amjad Khan; the couple had a son, Ahmed, a year later; two more would follow.

Causes related to the Muslim world appear to have drawn Siddiqui soon after she moved to the United States. As a student, she campaigned on the crises in Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Chechnya, raising funds and giving speeches at mosques “Perhaps”, an academic who knew her distantly in Boston speculates, “religious fervour was the only kind of self-expression her conservative family would not oppose.”

From soon after 9/11, though, her activism drew the attention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In 2002, Siddiqui and her husband were questioned about the purchase of some $10,000 worth of night-vision goggles, body armour, and military self-instruction books. The couple returned to Pakistan soon after, but divorced in August 2002.

In December 2002, Siddiqui returned to the US, on a trip she claimed was to apply for academic positions. In her time there, investigators later found, she opened a post-office box for Majid Khan, a Baltimore-based al-Qaeda operative alleged to have raised $50,000 to bomb a hotel in Indonesia, and to have plotted to blow up petrol stations in the United States.

From there on, her story became ever more opaque. Investigators claim she married Ammar al-Baluchi — nephew of 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed — on her return to Karachi. Then, at the end of March 2003 — 30 days after Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s arrest in Karachi — she simply disappeared. There are claims she was held by Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence; others suggest she hid out with Mohammed’s family, helped by the Jaish-e-Mohammad.

Also read: Pakistan Taliban ex-spokesperson who fled says ISI forced him to lie about India ‘terror funding’

An opaque story

Little of what happened next has become clear, but in 2008, the journalist-turned-activist Yvonne Ridley took up Siddiqui’s cause, after reading the passage about a mystery woman prisoner in Begg’s book. From the testimonies of other Bagram prisoners, Ridley received multiple accounts of a ghostly woman who kept other prisoners awake “with her haunting sobs and piercing screams”. In 2005, Ridley learned, upset prisoners had even staged a hunger strike in support of the woman.

The version offered by prosecutors, though, was very different. Five years after she disappeared, the FBI said, Siddiqui appeared in Ghazni, where she was arrested by Afghan police. In the course of her interrogation, the FBI alleged, Siddiqui snatched an automatic rifle a soldier had kept by her feet, and sought to kill him; she was seriously injured in the return of fire.

In 2010 — after a trial delayed, among other reasons, because of multiple assessments of her mental health — Siddiqui was sentenced to 86 years for attempting to murder United States officers. The allegations of her links to Al-Qaeda and terrorism were never prosecuted.

Evidence of anti-Semitic beliefs, though, emerged from Siddiqui herself. On one occasion, she wrote to the court that Jews are “cruel, ungrateful, back-stabbing” people, and attempted to sack her legal counsel because of their religious backgrounds.

The making of a martyr

Islamists in Pakistan soon began to remake Siddique into a living martyr. In September, 2010, as news of the guilty verdict broke, tens of thousands of protestors poured onto the streets of Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, and Quetta. Leaders of the largest Islamist party, the Jamaat-e-Islami, held multiple rallies over the coming years. Television shows were dedicated to campaigning for her release, featuring her sister and children.

Siddiqui, the scholar Khanum Sheikh has argued, became a metaphor for representing “the Pakistani state as feminised in its relationship to the US, and as unable and unwilling to disrupt US encroachments upon Pakistani sovereignty and against the larger Muslim world”.

“There is a difference between a friend and a slave”, now-Prime Minister Imran Khan said in 2009, using the case to assail the government of Prime Minister Asif Ali Zardari. “There are drone attacks being carried out”, he went on, “but our slave government will not take a stance against the US”.

In 2018, the Senate of Pakistan unanimously passed a resolution to take up the matter of Siddiqui’s freedom with the U.S., referring to her as “the Daughter of the Nation”

Later, in 2019, Imran Khan — by then Prime Minister — officially suggested that Siddiqui should be exchanged for Shakil Afridi, a Pakistani doctor accused of helping the United States confirm the identity of Osama bin Laden in advance of the raid in which he was killed.

The competitive mobilisation around the Siddiqui case has served only to undermine Khan’s legitimacy among Islamists, since the US proved uninterested in negotiating her release. In addition, the issue caused significant harm to US-Pakistan relations. The cause, however, was taken up with growing vigour by jihadist groups, who used it to argue that they, not Pakistan’s leadership, were genuine defenders of Islam.

(Edited by Rohan Manoj)

Also read: India must consolidate its gains in Kashmir. Jihadist groups eyeing expansion opportunity