New Delhi: Most of Homai Vyarawalla’s first set of published photographs were attributed to M.J.V., the initials of her husband, Maneckshaw Vyarawalla, and then later to the pseudonym ‘Dalda 13’. It was not anonymity she sought, but a means to navigate her way through a time when most women were relegated to the home, while she was busy fighting batteries of men, in her crisp khadi saree with a camera around slung around her neck, to get the perfect shot.

She fell into photography as swiftly and accidentally as she fell in love with Maneckshaw at a railway station at the age of 14. What started off as a mentor-mentee relationship soon transitioned into one of partners, who taught themselves through tips picked up in photography journals and old Kodak pamphlets. Both her personal and professional life were so inextricably linked with him that it is no wonder that she retired from photography and became a recluse once he passed away.

The fact that until recently, there were no formalised frameworks, retrospectives or archives to study the history of Indian photography made it easier for Vyarawalla and her incredible body of work to fade into obscurity.

But researcher Sabeena Gadihoke’s book Camera Chronicles of Homai Vyarawalla, a National Gallery of Modern Art retrospective on her work, and Anik Gosh’s documentary film Homai Vyarawalla (2006), all contributed to a palpable surge of interest around the woman who has been dubbed India’s first photojournalist.

On her 106th birth anniversary, ThePrint takes a look at the significance of Vyarawalla’s legacy.

Developing a practice of her own

From the very beginning, Vyarawalla was clear about what kind of a photographer she was not. Gadihoke’s memoir details how Vyarawalla experimented her way into mastering her craft by developing negatives in her bathroom-cum-dark-room and glazing her prints on her mother’s charcoal gas stove, but eventually grew a great disdain for “staged” photographs, often dismissing studio photography as “armchair photography”.

“I have never asked anyone to pose for me. I don’t like it, because the moment the subjects know that they are being photographed, a change comes over their countenance. The whole atmosphere changes. The body becomes stiff and eyes open up a bit, which is not natural. When you take a picture, it’s always in a split second. You either take it or miss and that must be the right moment,” Vyarawalla told Gadihoke.

A proponent of the growing candid photography style, she firmly believed in being out and about in the streets to physically engage with spaces and subjects. She eschewed bulky studio equipment, which Susan Sontag once called “cumbersome and expensive contraptions — the toy of the clever, the wealthy and the obsessed”, and started using smaller, more portable cameras like the Rolleiflex and the Contax that allowed her mobility and ease.

“The moving away from studio photography was not just about technology but also an era of candid photography and a reaffirmation of the belief that the camera captured reality,” explains Gadihoke. Thus, as the foundations of photojournalism were beginning to be laid, making photos look “realistic” started to become increasingly important.

In this attempt to move away from traditional in-studio portraiture, Vyarawalla and Maneckshaw began to work with publications like The Illustrated Weekly of India and The Bombay Chronicle on photo features centred around Bombay — the first of their kind. Her early photographs recorded Bombay’s dynamic urban life in an ethnographic fashion, from horse-driven tram cars and glistening streets to the city’s festivals and daily work activities of its diverse residents.

This was also a time when photographs were starting to be seen as a means of information. “The information that photographs can give starts to seem very important at that moment in cultural history when everyone ought to have a right to something called news,” wrote Sontag in her seminal work On Photography, adding that photographs started to represent a “thin slice of space as well as time”.

Hence, when the Vyarawallas were employed by the British Information Service (BIS) in the early 1940s, it was part of a growing trend of making “information films”. She photographed fisherwomen, agricultural labour, documented processes of cotton-ginning, toddy-tapping and brick-making.

Many of these photographs that were printed in The Illustrated Weekly of India were part of the British government’s way of highlighting efforts of progress in India, along with calls for Indians to help with World War II — like Vyarawalla’s spreads of Parsi women being trained in rescue activities during the war. The photographs then, in a sense, started to reflect British interests, with Vyarawalla no longer just someone photographing subjects, but part of a larger framework of information creation and dissemination.

From being shy of politics to being at the centre of it all

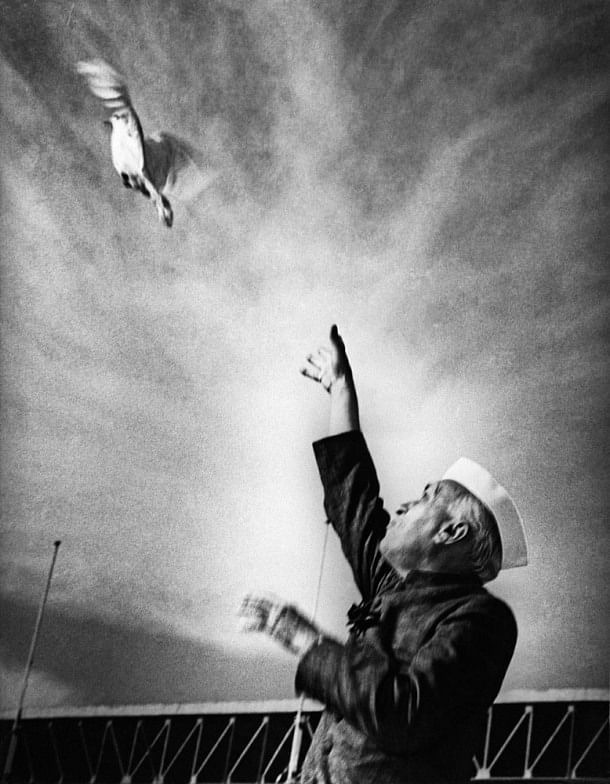

Vyarawalla eventually came to be known as one of the most important press photographers at the time of the freedom struggle and the building of India as an independent nation. Some of her most celebrated photographs include those of Nehru’s initiation into prime ministership, the reception hosted by Lord Mountbatten on Independence Dayat what would later become Rashtrapati Bhavan, the first flag hoisting at the Red Fort, Mahatma Gandhi’s funeral, the Bandung Conference in 1955, and the Dalai Lama entering India for the first time through Sikkim in 1956.

But one must remember that Vyarawalla was from a simple, conservative family belonging to the Parsi community that was largely ambivalent towards politics. When she was growing up, Parsi girls were forbidden to take part in politics and were made to wear silk sarees, never cotton khadi, as that had associations with Gandhi’s Swadeshi movement. As Gadihoke explains in her book, Parsis had a complicated relationship with the nationalist movement because, apart from their general “distaste for street politics”, many developments like the land-to-the-tiller movement and prohibition resulted in huge losses for land and business-owning Parsi families.

Yet Vyarawalla, who only read about the independence movement while she was in school, eventually found herself at the centre of it all, often much to the dismay of others. “I was bold about what I wanted to do. Those were days when women were not supposed to carry handbags. They were not supposed to have any pockets either, because of the sari, and carried their cash in their blouses,” she told Gadihoke. “I still remember, someone asked me, ‘Kya hajamat karne ja rahi hai? (Are you going to work as a barber?)’. I replied, ‘Haan… kya aapki karwani hai? (Yes, would you like me to cut your hair?)’”

Almost 50 years on, female photojournalists are still an exception in newsrooms rather than being a norm. However, Vyarawalla’s work is not just significant because of her gender, but the fact that she ended up being a chronicler of a politically charged era “without realising how significant her images were to become”.

Famous for her proximity to Nehru, her countless pictures of Indira Gandhi and her ability to capture the camera-conscious Gandhi, Vyarawalla’s practice also signified a time when intimacy with political leaders was possible.

“That kind of access is impossible today — the last person to give that kind of access was perhaps Indira Gandhi, one of the most photographed woman leaders of that time. There has not been intimate work of that kind in more than two decades,” Hindustan Times’ head of national photography desk Paroma Mukherjee tells ThePrint.

“Senior journalists tell me there was still a time, post-Nehru, when there was a sense of openness. The prime minister would come out in the lawn, be photographed, and go back in. Gandhi himself had about 100 photographers who would follow him on his processions, Nehru did too.

“Today, things are entirely different. You need a PIB card, special permissions, security is tight and there is a huge sense of suspicion towards anyone who has a camera,” Mukherjee says, adding that there is too much security around the political class who only surround themselves with official photographers.

In today’s smartphone age, when everyone has a camera, Instagram filters and editing apps, it is perhaps hard to imagine the pains Vyarawalla took to develop her technical craft. But considering both the omnipresence of the photographic image and suspicion for anyone with a camera, she represents a simpler time where photojournalism was a noble profession that sought the pursuit of truth.

Also read: Mamoni Raisom Goswami — the voice of the oppressed who fought for peace in Assam