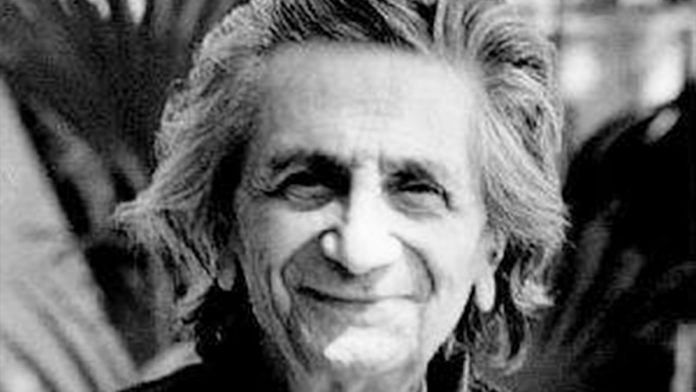

New Delhi: Bhisham Sahni, born on 8 August 1915, is considered to be among India’s greatest writers and a distinguished voice in Hindi literature — having written over 100 short stories and several plays. Sahni, who was born in Rawalpindi, in present day Pakistan, was an active participant in the Quit India Movement, and settled down in India after Partition.

Tamas, Sahni’s most celebrated novel, is a product of the Partition’s devastation. It drew immediate and universal critical acclaim for its poignant and striking retelling of Partition and its bloody aftermath. So compelling is the book that it has been translated into English three times — most recently in 2018 — and also made into an iconic TV serial by Govind Nahalani.

Sahni’s writings earned him the Shiromani Writers Award in 1979, Padma Bhushan in 1998 and Sahitya Akademi fellowship in 2002, among countless others.

On his 16th death anniversary, 11 July, ThePrint revisits Tamas, a story about how simmering communal tensions snowball into full-fledged riots that grip villages across the subcontinent.

In the excerpts below, some Congress workers are cleaning drains in a Muslim neighbourhood when they spot the carcass of a pig outside a mosque.

“Something’s going on somewhere,” said Bakhshi to Mehta.

“Who knows, maybe Kashmiri or Shankar teased a girl from the mohalla. You’re the one who let loafers into Congress.”

“What are you talking about, Mehta ji? Kashmiri was cleaning the drains the entire time. It seems like some other kind of thing is going on around here.”

When they turned into the gali of the Mohyals, they saw three or four men standing at the entrance.

“Where are you going, Bakhshi ji, don’t go that way,” said a tall Mohyal man, an acquaintance of Bakhshi’s, coming forward.

“What’s wrong?”

“Just don’t go over there.”

“But what happened?”

At that moment, Kashmiri Lal, the General and Master Ram Das also walked up to Bakhshi and Mehta.

“Look over there, outside the gali.” Bakhshi looked up ahead. Outside the gali, across the street, there was a mosque known as Kelon ka Masjid.

“What is it? Don’t you notice anything? Look at the steps leading up to the door of the mosque.”

Something black lay on the steps.

“Someone threw a dead pig over there.”

Bakhshi looked at Mehta as if to say, “See! Didn’t I tell you? There’s something wrong.”

Everyone turned and looked — on the steps of the mosque they could see something that looked like a black sack from which protruded two legs. The green door of the mosque was closed.

“Let’s go back, let’s get away from here,” said Master Ram Das softly.

Kashmiri Lal looked over at the pig and spat contemptuously. He turned his face away.

“Someone is up to some kind of mischief,” murmured Mehta.

“You know for sure it’s a pig?” he asked.

“Maybe it’s some other animal.”

“If it were some other animal, would the Muslims be so upset?” asked Bakhshi with irritation.

The General was also staring at the mosque, his tiny eyes hidden beneath his beetling eyebrows. Suddenly he cried out, “The English threw it there!”

His nostrils flared and again he shouted, “It’s the mischief of the English, I know it is.”

“Yes, yes, General, it’s the mischief of the English, but you keep quiet right now,” Bakhshi admonished him.

“Let’s go home through the last gali we passed,’ said Master Ram Das again.

But this time, the General thundered at him, “You’re a coward! This is the mischief of the English! I will expose them!”

At this, Mehta leaned over and whispered into Bakhshi’s ear, “Why do you always bring this nut along? He’ll get us all killed. Throw him out of Congress.”

A Muslim passed quickly by on the street and the moment his eye fell upon the stairs of the mosque, he turned and looked at the bundle, then, turning his face away, he walked on, muttering.

Suddenly, a tonga came galloping into the street. After that, there was the sound of running footsteps from the other side of the mosque. The butcher across the street to the left draped the goats hanging in the window with cloth and shuttered his shop. The doors of homes and shops in the gali of the Mohyals began to shut one after the other.

Bakhshi turned and looked. Master Ram Das had slipped away and was walking at a distance towards the entrance of the gali. Aziz and Sher Khan were walking a bit behind him as well. Small groups of people stood about in the lane.

“Get out of here, Bakhshi. If you people stick around here, it will mean trouble,” his Mohyal friend advised him.

Bakhshi looked at him, and then said to Kashmiri Lal, “Take the flag from the pole and fold it up.”

Then he said to the Mohyal gentleman, “Let’s get that pig carcass out of here. As long as it’s lying there, tensions will mount.”

“You’re going to pick up a pig carcass?” asked the Mohyal with dismay. “I don’t think you should go anywhere near it.”

“I agree with him,” said Mehta. “We shouldn’t get involved in this. Things could get worse if we do.”

“But won’t it get worse if we leave? Are the Muslims going to remove it?”

“If they won’t remove it, some water carrier or sweeper will take care of it. We shouldn’t get involved no matter what.”

Bakhshi set his lantern down on someone’s front step. Then he turned to Mehta, and said, “What are you talking about, Mehta? You think we should get out of here quickly and let the tensions increase? It would be different if we hadn’t seen it with our own eyes.” Then, addressing Kashmiri Lal and the General, he said, “Come with me,” and walked out of the gali towards the mosque.

Kashmiri Lal wondered if he should go or not. Rocks had been thrown at them in Imam Din Mohalla; who knew what would happen here? He broke into a sweat. He leaned the flagpole against the wall and stood there hesitating. His legs felt shaky. By this time, the General and Bakhshi had already crossed the street. Kashmiri hesitated for a moment, then followed them out of the gali. When he reached the street, he turned to look back. The Mohyal gentleman had already left and only Mehta remained. The entire gali lay deserted. To the left there were three or four shops. All were closed. At a distance, on the right, near the well, there was a row of shops that were all closed as well. A small clutch of people stood near the well staring in his direction. He had the sensation that there were people watching from their balconies, but the doors of the houses were all closed.

“First of all, let’s get this pig carcass out of here,” Bakhshi was saying.

It was a black pig. Someone had covered it with a sack, but its legs, snout and belly were sticking out.

Mehta was still leaning against the wall of the gali. He was in a quandary. Removing the pig was a dangerous job, and it was also dirty; he worried it might muddy his brilliant white khadi. Bakhshi and the General grabbed the pig by the legs and dragged it down the steps of the mosque and across the street, where they hid it behind a pile of bricks.

“Let’s put it here for now. That way the door of the mosque can be opened. Let’s clear the steps to the mosque,” said Bakhshi, and to Kashmiri Lal he said, “Go to the sweeper community over that way, Kashmiri. That’s where the municipal sweepers live. Look and see if two of them will bring a wheelbarrow over, then they can lift it up.”

Then came the sound of running footsteps from the direction of the well. The three of them turned to look. A cow was running towards them. A man with a staff in his hand and a small turban on his head raced after the cow, driving it along. The top buttons of his kameez were open and a taweez swung from his neck. It was a shiny almond-coloured cow, with huge, startled eyes, its tail lifted in fear. Perhaps it had been lost. The three of them stopped. The man with the turban had his face covered. He drove the cow past them on the street and then into a gali to the right.

Bakhshi stood still for quite a while. Then he said softly, “It seems vultures will fly over the city. The signs are very bad.” He looked even more pale and serious than before.

Also read: Balraj Sahni, the common man’s hero who told their story through cinema

(The excerpts have been taken from the novel translated by Daisy Rockwell in 2018.)