Words were Ramashankar Yadav ‘Vidrohi’s’ weapons of choice. Like an expert swordsman, he wielded them in his fight against religious superstition, gender discrimination and inequality. Jawaharlal Nehru University was his alma mater, its vast campus his home till his death on 8 December 2015.

The poet and activist whose life is intertwined with JNU embodied the ideals of a rebel poet. “JNU is my workplace. I have spent my days in the hostels, in the hills and forests here,” he often said.

Students would wait for Vidrohi’s poems at the end of their demonstrations. He was their voice on campus. He would not only participate in student agitations but would also enliven them with his poems.

“Ganga Dhaba was his permanent address and he considered all comrades as his own. He had authority over them,” Sucheta De, ex-president of JNU Students Union and currently a central committee member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation, told ThePrint.

Seven years after his death, he remains a symbol of rebellion and revolution.

Also read: From battling caste to redefining epics, why Kannada poet Kuvempu is relevant even today

JNU: A love like no other

Ramashankar Yadav was born on 3 December 1957 at Ahiri Ferozepur village of Sultanpur district in Uttar Pradesh. As a child, he dreamt of studying at a prestigious university. He wanted to study law and enrolled in an LLB college in UP. However, he was eventually expelled for his involvement in student politics.

He enrolled in JNU in the 1980s for postgraduate studies and was rusticated once again for his participation in a 1983 student agitation. But he refused to leave the university premises. In 2010, he was reportedly removed from campus for allegedly using abusive language in a public place but was allowed to return after students took up cudgels on his behalf.

Vidrohi’s routine would start with a morning tea at the university canteen after which he often frequented Ganga Dhaba. Ganga Dhaba is one of JNU’S most sacred spots, one where politics and society are discussed over steaming plates of food.

Such was JNU’s allure that Vidrohi preferred to spend his nights in its forests. But he moved to the student’s union office later, where he would retire each night till his death.

“I can stay in the students’ union office for one more year without fear now,” Vidrohi told now Congress leader Kanhaiya Kumar after he became president of the JNU Students Union in 2015. “He will stay here forever,” declared Kanhaiya.

When his poems were published in BBC Hindi, he took out copies and distributed them among students.

Also read: Sudama Pandey ‘Dhoomil’—angry young man who became poet of the masses

JNU was his muse

His poems, which he would recite orally on campus, earned Ramashankar Yadav the title, ‘Vidrohi’.

“We entered the campus with a dream to change the world and Vidrohi’s poetry has a big role in it. His poems had a deep voice of protest and a dream of a different world,” said De.

Vidrohi practised the oral tradition of poetry. He eschewed a pen and paper and composed verses in his mind, which he would then recite enthusiastically and aggressively. The intellectual culture of JNU was his muse.

After much prodding by students, Vidrohi released one book—his only published work— a poetry collection called Nai Kheti, which came out in 2011.

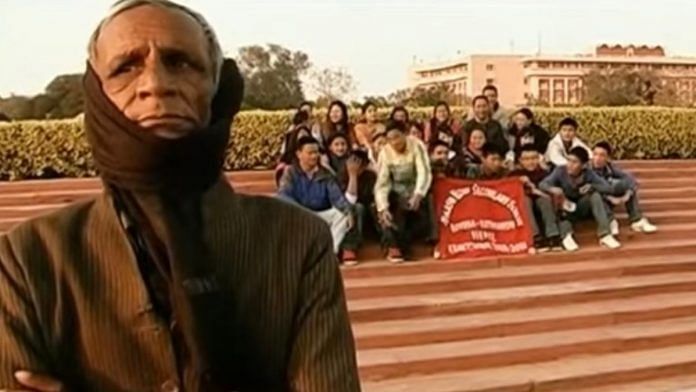

That same year, director Nitin Panmani made a documentary called Main Tumhara Kavi Hoon (I Am Your Poet), which drives home the image of Vidrohi as a revolutionary poet who has no material possessions. When he’s asked how he survives Delhi’s harsh winter and scorching summer he replies, “Everything rots, dissolves, disappears and yet people keep giving.”

The film ends with the poet condemning kings and empires for rising to power on the backs and bodies of slaves—the crimes of civilisations. He says that patriarchy is a product of history and that at the mouth of every civilisation, a burnt corpse of a woman and scattered bones of humans are found lying.

Though his words are bleak, he also uses humour to get his point across. “As for God, he looks after the king’s horses. He’s a nice fellow, God… He died ages ago.”

He goes on to say: “Historians can also tell you that the king died, the queen and the prince. The king in battle, the queen in the kitchen, the son from too much school.”

The bard of JNU attended protests and challenged authority through verse. Protesters relied on the strident cadence of his poetry to get their message across.

“Har jagah narmedh hai/har jagah kamzor mara jaa raha hai, khed hai (Human beings are being sacrificed everywhere / Regretful how the weak are being killed everywhere),” he declared during one protest, lending his voice to the deprived and the exploited.

While reciting his poem Aurat (Woman), he made a passionate argument against the restrictions that women face.

“Who was the first woman in history, which was first lit, I don’t know, But whatever it may have been, must have been my mother,” he said.

Also read: Before PS:1 and Baahubali, Sohrab Modi gave India one of its first big-budget epics

Undying commitment to the Left

Ramashankar Vidrohi’s commitment to the Left was well-known. He was often heard quoting Karl Marx and Bertolt Brecht, a Communist poet and playwright from Germany. “Communism is not madness, but it is the end of madness,” he said while quoting a few lines from In Praise of Communism, one of Brecht’s most famous poems.

He was very active during the ‘Occupy UGC (University Grants Commission)’ movement of JNU in 2015 when students were agitating against the UGC proposal to discontinue the non-National Eligibility Test (NET) fellowship for scholars. But when Vidrohi returned to campus after the protest march at Jantar Mantar, his health suddenly deteriorated and he died in his sleep.

“He is not a person but an ideology and a symbol of collective imagination. As long as JNU continues to move forward with progressive thinking, Vidrohi will remain alive. Just like comrade Chandu and Gorakh Pandey”, De said.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)