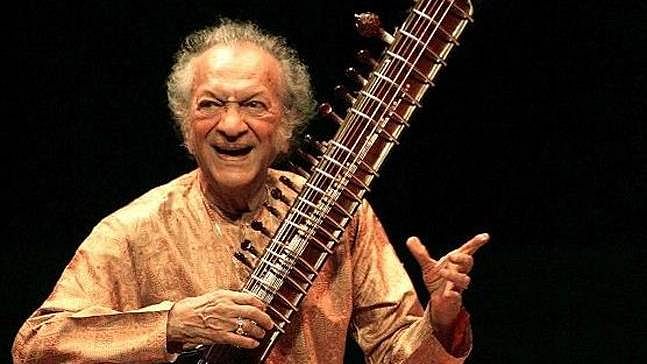

New Delhi: One would expect Pandit Ravi Shankar — among India’s finest musicians who perfected the art of playing sitar — to fit in well with a long-haired, joint-smoking, ‘hippie’ crowd, given his openness to experimentation and foreign cultures.

However, his exposure to the almost universally loved Woodstock festival in the US left him horrified: “When you go to listen to Bach or Beethoven or Mozart, do you behave like that?” he said about the ‘misbehaving’ and intoxicated crowd at the festival.

For Shankar, classical music was an intoxicant itself. “Please try to listen with a pure mind,” he told the crowd, “Because I assure you that our music has that power that it can make you feel high.”

By orthodox Hindu standards, Shankar’s string of lovers and contributions to western pop music should have rendered him a lost cause. His seemingly old fashioned remarks on Woodstock festival, however, reveal a didacticism and commitment to retain the purity of his craft. To Shankar, music was strictly spiritual, if not religious.

He came, after all, from one of India’s most pious and musical cities, Benaras (now Varanasi), where he was born on 7 April 1920. He spent the first decade of his life in Benaras and then moved to Paris to join his brother Uday’s dance troupe.

Between Paris and India, Shankar first heard his guru-to-be, the renowned sarod player Ustad Allauddin Khan, in 1934 at a concert in Calcutta.

“He was the first person frank enough to tell me that I had talent but that I was wasting it — that I was going nowhere, doing nothing,” Ravi Shankar said of him. “Everyone else was full of praise, but he killed my ego and made me humble.”

Three years later, in 1937 at the age of 18, Shankar packed his bags to return to India and its musical heritage. Eating humble pie meant shifting to a tiny town in Madhya Pradesh called Maihar, practising relentlessly for hours on end, and shedding all the flashy dance costumes from his dancing days. Shankar emerged in 1944, with a full training in Hindustani sitar.

That same year, Shankar married Annapurna Devi, his guru’s daughter, but the marriage went through choppy waters. Annapurna was thought to be more talented than him, and she gave up live performances to ease the strain on their marriage. Shankar’s habitual infidelities only made things worse, and they eventually divorced in 1982.

Also read: Ustad Bismillah Khan, a Muslim who reveled in the sound of shehnai in Varanasi

Shankar and George

Shankar’s fascination with taking Hindustani classical music to the West began early. Till the late 1950s, he used to lecture, teach and play in the United States.

It was in 1966 that George Harrison, lead guitarist of The Beatles, approached Shankar for lessons after dabbling with the sitar on his own.

“When George Harrison came to me, I didn’t know what to think,” Shankar said. “But I found he really wanted to learn. I never thought our meeting would cause such an explosion, that Indian music would suddenly appear on the pop scene.”

Harrison lacked the fastidiousness required by the Hindustani classical form, and gave it up two years later. The short time that Shankar mentored Harrison, however, led to a lifelong bond. In the time, they played together; they made enough music for a four disc compilation, called ‘Collaborations’. Together, they played in the ‘Concert for Bangladesh’, organised by Harrison after Shankar suggested it, which earned him a Grammy award.

So intimate was their relationship that Harrison wrote the forward for Shankar’s second autobiography, Raga Mala, where he said: “The moment we started, the feelings I got were of his patience, compassion and humility. The fact that he could do one of his five-hour concerts, but at the same time he could sit down and teach somebody from scratch the very basics: how to hold the sitar, how to sit in the correct position, how to wear the pick on your finger, how to begin playing…And he enjoyed it, he wasn’t grudging at all, and he wasn’t flash about it either.”

And so, whether he liked it or not, his association with Harrison and The Beatles made him infamous. He went on to collaborate with American violinist Yehudi Menuhin in 1967, playing with him at the UN Human Rights Day concert that year. He also mentored jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, and collaborated with ‘minimalist’ composer Philip Glass in 1990.

After the Bangladesh concert, Shankar won three more Grammys: Album of the Year in 2001 and 2012 (for ‘Full Circle – Carnegie Hall 2000’ and ‘The Living Room Sessions Part 2’, respectively), and a Lifetime Achievement Award posthumously in 2013.

Back in India, Shankar was endowed with all the three highest civilian awards — Padma Bhushan in 1967, Padma Vibhushan in 1981, and Bharat Ratna in 1999.

Shankar’s talented progeny

Shankar’s first son, Shubhendra Shankar, was also a musician, but died of pneumonia in 1992 when he was 50 years old.

After divorcing Annapurna Devi, Shankar had trysts with several women. Among them was Sue Jones, an American concert producer. Shankar and Sue’s daughter Norah Jones was born in 1979, and is a renowned fusion jazz singer. They never, however, had a close relationship and avoided talking about each other to the media.

Shankar was much closer to Anoushka Shankar, his daughter with Sukanya Rajan whom he was married to till his death. Anoushka was born in 1981. Shankar taught Anoushka the sitar and the two began playing together by the time she was 13 years old.

In an interview with The Guardian, Anoushka said, “Being taught by him gave us, I think, an almost unique relationship. It gave us a deep connection because we suddenly had this whole undercurrent of communication that you can only really get when you play music together.”

Shankar’s death on 11 December 2012 after undergoing a heart valve replacement surgery left the whole world in mourning. “It was Shankar’s vision that brought the sounds of the raga into western consciousness”, said The Guardian in an obituary, “He was thus the first performer and composer to substantially bridge the musical gap between India and the west.”

Also read: Gangubai Hangal championed tradition to excel in male-dominated world of Hindustani music

A beautiful spirit and musician. His performance at Monterrey in 1967 was awe-inspiring and caused me to look further into his beautiful music.

Thank you and Happy Birthday Ravi