New Delhi: A pioneer of Hindi literature’s Chhayavaad movement in the early 20th century, Harivansh Rai Bachchan had a way with words. His writings are said to have given shape to modern Hindi poetry along with the contributions of Jaishankar Prasad, Sumitranandan Pant and Mahadevi Verma and others.

With 30 collections of poems to his name, Bachchan wrote on a range of issues, from politics to love and philosophy. He was also a talented translator, deciphering the writings of Omar Khayyam, W.B. Yeats and William Shakespeare. In fact, for his work on Yeats, he received a Ph.D. in English Literature from Cambridge University, the first Indian to do so.

Born on 27 November 1907 in Babupatti village, in what was then the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Harivansh Rai Srivastava (he changed the family name to Bachchan years later) grew up, as detailed in his autobiography (translated into English by Rupert Snell as In The Afternoon of Time), in a large Brahmin family that was often wrought with financial troubles. He did his early schooling and graduation in Allahabad, and then went abroad to attend St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge University.

On returning to India, he joined All India Radio in Allahabad and then the Ministry of External Affairs, where he made efforts to make Hindi the official language of India. He was nominated to the Rajya Sabha in 1966 and a decade later, was awarded the Padma Bhushan for his contribution to Hindi literature.

Here is a look at his legacy through his most well-known work, Madhushala (The House of Wine), and his autobiography.

Qualms with orthodox religion

Throughout Madhushala, wine is a staple metaphor that denotes life, death, artistic inspiration, love and belief. The poet’s take on belief or god is described in the translator’s introduction as “far from the Hindu devotional spirit” and closer to ideals of Sufism. Sample these lines on the institutions of religion —

“He who has calcined all the creeds

With fire from his burning breast,

Who quits the temple, mosque and church

A drunken heretic, unblest,

Who sees the snares, and now comes running

From Pandit’s, Priest’s and Mullah’s cunning,

He, and he only, shall today

Be in my House a welcome Guest.”

These ideas are expressed more explicitly in his autobiography, in which he describes his tussle with religion and finally letting it go: “I had long since freed myself of any religious conventions, even if my religious instincts were more deeply rooted and could not be disposed of so easily.”

Also read: As India mourns legendary Neeraj, is the era of poetry over in Bollywood music?

Love and dependence

In the following lines, Bachchan describes a male lover yearning for his beloved but is only left vulnerable and disappointed.

“Into your hands, and at the brink

All woman-like, the Wine retreats

Before the longing lips may drink

Often before she tilts the vial

The Saki mocks with soft denial;

Be not surprised, O traveller,

When House and Handmaid seem to shrink.

This Wine resembles fire, and yet

Do not refer to it as flame

Nor call the bubbles at the brim

Blisters of frustrated love and shame:

Where your dead memories serve and languish

This Wine will make you drunk with anguish;

And can a man take pleasure thus…”

A lover’s anguish is a classic trope in Sufi poetry but a parallel can be found in Bachchan’s real life too — his mother’s unflinching devotion for her husband. According to the poet, his mother, Sursati lived in service to his father. The day she left home for her in-laws’ house, her mother handed her the Ramayana and marked out a passage on Sita’s “wifely conduct”. Serving one’s husband became a virtue in Sursati’s eyes — but not in her son’s.

In his autobiography, Bachchan is highly critical of his mother’s dependence on his father as it left her helpless in widowhood.

“Sursati had married Pratap Narayan to follow him in all his desires and ambitions, and remained dedicated to this ideal her whole life long; eventually, when her husband passed away, she had to pay a pathetically high price for this exclusive dependency. ‘What would he say or do if he were here now?’ became the catch-phrase of her widowhood…”.

Collapsing barriers of power

In the early stanzas of Madhushala, Bachchan wrestles with the art of writing and the pressures of pleasing audiences. As mentioned before, wine represents many things in this poem, but by interpreting it as art, Bachchan appears to collapse power dynamics between the artist and the receiver of art.

In the beginning, he describes himself as an artist serving the divine world. “You, Goddess, taste my first libation; My House of Wine shall honour you before the thirsty crowd draws near.” Then, he acknowledges, the “thirsty crowd” by saying “The poet is the Handmaid now who offers many a flowing line; And in the Cup where millions drink The Wine I press can never sink. My readers are my thirsty Guests, My Book of Verse a House of Wine.”

However, by giving himself into the art he creates, the poet also belongs to the bottom of the hierarchy as a slave to his own work.

“I daily press as I have pressed;

With this sweet Wine I fill the Cup,

That thirsty Cup, my heart’s unrest;

Where my imagination lingers

It lifts the Cup in magic fingers;

I drink; and lo! I am myself

The House, the Handmaid and the Guest”

Here, Bachchan collapses levels of hierarchy to show that the poet is equally divine and ordinary. This echoes his political beliefs on class and equality that comes through in a passage from In The Afternoon of Time about an odd birthday tradition in his household.

When children celebrated their birthdays, their body weight would be weighed against grains, produce or sweets. A large weighing scale would be brought out, the child would be propped on one side and a range of goods would be loaded on the other until the scales reached equilibrium. Then, all the grains and sweets measured would be given to servants and beggars in the neighbourhood.

On this, Bachchan comments, “What strange ways Hindu society has contrived to drive home a bitter awareness of the distinctions between the high-born and the low!”

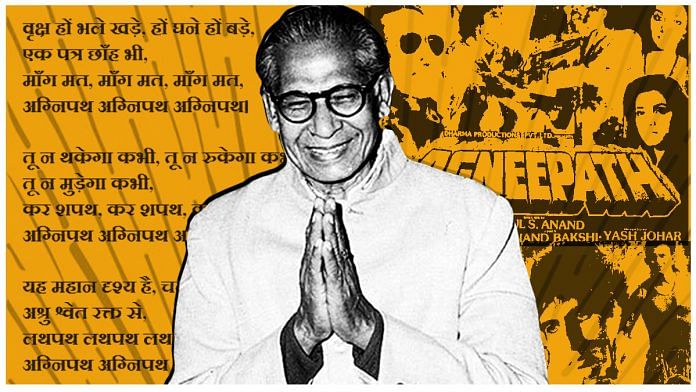

Bachchan passed away in 2003 at the age of 96, leaving behind a legacy of literature that is still seen today (his famed work Agneepath lent its name to his son Amitabh Bachchan’s Bollywood movie and its remake starring Hrithik Roshan. Both movies also featured couplets from the poem).

Also read: Abhimaan, the timeless classic, had shades of Amitabh & Jaya Bachchan’s real lives