In the November 1918 edition of his monthly magazine Young India, editor Lala Lajpat Rai penned a short commentary on Ananda Coomaraswamy’s notes on the Ramayana.

“These notes presuppose a knowledge of the story of the Ramayan on the part of the reader. We do not know how far that supposition is justified in this country [USA]. It would have been better if Dr. Coomaraswamy had given a brief account of the story also,” Rai wrote in the issue published from Broadway in New York by the India Home Rule League of America.

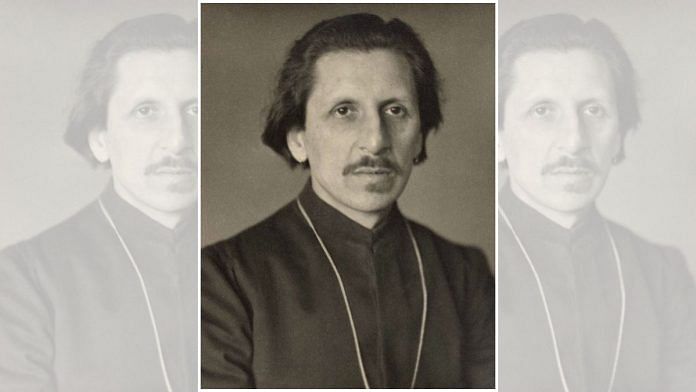

Both Rai and Sri Lankan-born Tamil-American metaphysician, art critic, and philosopher Ananda Kentish Muthu Coomaraswamy were in exile at the time.

Rai went to London as a member of the Congress delegation in 1914 and was not allowed to return before the end of World War I. Coomaraswamy last visited India in 1915, and after returning to England, was forced to leave the British Empire before the end of the next year due to his participation in the Indian Independence movement.

Coomaraswamy had studied in the UK and died in the US. But he loved India more like any true Indian since his first visit in 1906.

Also Read: How unique ‘Bazaar paintings’ fuelled trade in colonial India

Passage to India

Coomaraswamy started the voyage from Sri Lanka to India on 28 December 1906. Before that, he was the founder-director of the Geological Survey of Ceylon (Sri Lanka). This was when the partition of Bengal was a part of the public discourse along with the Swadeshi movement. Leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal and Aurobindo Ghose were defining Indian nationalism. After two months of travelling to different parts of India, Coomaraswamy went to England. For the next eight years, he continued visiting India in his quest for a suitable role in the freedom movement and to explore the arts and crafts of India.

The overt expression of Indian nationalism became evident in his 1907 speech delivered at Cheltenham. Some of his books, such as Essays in National Idealism (1909) and Art and Swadeshi (1912), were testimonies to this influence. Major parts of Coomaraswamy’s life and work were profoundly impacted by 19th-century British scholar and author of Unto this Last, John Ruskin, and socialist artist and author of News from Nowhere, William Morris.

Coomaraswamy started the India Society in London with painters William Rothenstein and Roger Fry, art historian EB Havell, and others in 1910. British orientalist and scholar of Pali language Thomas William Rhys Davids became its first president and musicologist Arthur Henry Fox Strangways its secretary. One of its top achievements was launching poet Rabindranath Tagore with the publication of Gitanjali, which won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913.

Before that, Coomaraswamy had spent many moons with the Tagores in Calcutta (now Kolkata). He was appointed president of the National Committee for Indian Freedom formed in 1914 in Washington. The same year, when MK Gandhi reached London after tedious experiments in South Africa, Coomaraswamy received him at Caxton Hall along with Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Sarojini Naidu.

His son Rama Coomaraswamy, in a penned sketch published by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, described how his father was involved in the Indian Independence movement. “During the First World War, he refused to serve in the British army as long as India was under British rule. As a result, he was exiled from the British Empire and his home Norman Chapel, was confiscated and was made part of the English National Park Service,” Rama Coomaraswamy wrote.

Also Read: Jailed at 13, S N Subbarao went on to rehabilitate 600 dacoits in Chambal valley

Exiled from UK

Ananda Coomaraswamy’s house, Norman Chapel, was situated in a little village called Broad Campden, around 90 miles apart from London. Coomaraswamy procured the house through British architect Charles Robert Ashbee, who renovated it and converted it into a double-storey building, while maintaining its original 12-century structure and design—all this before Coomaraswamy (along with his wife) returned from his first trip to India in 1907.

People associated with the Independence movement visited him in his house. Ashbee’s wife Janet recorded one such occasion in 1908, when a disciple of Swami Vivekananda, Sister Nivedita (Margaret E Noble) was invited to deliver a lecture at Norman Chapel.

In India, Coomaraswamy’s nationalist polemics remained unsuccessful due to his patronising rants against the educated middle class. He had opposed this class buying clothes illustrated with bicycles or banknotes in favour of traditional design.

“The Brahminical caste system is the nearest approach to a society where all interests are considered identical and is the only true communism,” he said in another context. He also justified sati.

Most of his writings failed to get a wide audience in India, but he steadily made a name for himself as an art historian in Europe and the US.

At the same time, his nationalist activities and regular visits to India made British authorities suspicious, and they began to explore his links with the Ghadar Party, founded by expatriate Indians in the early 1900s, the Ghadar Movement aimed to overthrow the British colonisers.

When Britain revised the Military Service Act during World War I, Coomaraswamy refused to serve even in a wartime civilian role. In such circumstances, he planned to seek asylum in the US with the help of his friend Denman Waldo Ross, who was a trustee of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and lecturer of art and design at Harvard University.

Ross had helped him considerably. He had procured the collection of Coomaraswamy’s art for the Boston Museum when the British Home Office and Scotland Yard were trying to make his life difficult. This was clear in Coomaraswamy’s correspondence with close friends like Rothenstein. “I am still harassed about the permit to leave, have spent several hours at Scotland Yard—the difficulty is due to the words in a speech I made at Cheltenham in 1907! It is a bitter irony altogether,” he wrote.

Coomaraswamy’s biographer Roger Lipsey wrote about his role in the nationalist movement but kept quiet about the Cheltenham speech.

At last, Coomaraswamy managed to evade Scotland Yard and reached the US in December 1916 with his art collection and the bulk of his inherited fortune. He was part of the curatorial staff at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts for the next three decades. While describing him, his colleague Eric Schroeder said, “He felt interest in present history, the industrialist rape of Asia and the prostitution of Western intellect to the contingent, but his delight was in metaphysics.”

Coomaraswamy returned neither to Britain nor to India. But just before his death, after an interview, S Chandrasekhar wrote that he was planning to return to India after an absence of three decades. Coomaraswamy wanted to settle down at the foot of the Himalayas and join the vanaprastha and sanyasa ashram.

After his death on 9 September 1947, his wife Dona Luisa Coomaraswamy returned his ashes to the holy Ganga. At the turn of the century, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts paid Rs 50 million to procure the remaining part of his collection from his son Rama.

In 2015, the Indian High Commission bought the house in London where Bhimrao Ambedkar lived as a student during his time at the London School of Economics. Today, the governments of India and Britain need to think similarly about Norman Chapel to pay tribute to its one-time owner, Coomaraswamy. It will be a tribute to the seer, who introduced the West to the art and culture of the Indian subcontinent.

The author is an environmental activist. He tweets @mrkkjha.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)