New Delhi: From the madrasas around the southern fringes of Dhaka, students marched towards the poet’s house as if they were headed to prayer. There was, he had written, ‘a dark flood under a dark full moon under the dark sun’.

Led by the Islamist leader, Muhammad Kamaruzzaman, many of those very students had served in the Al-Badr and Al-Shams militia, responsible for a series of genocidal massacres in the war of 1971.

Forgiven their crimes, they had emerged on the streets again, this time to burn down the home of Daud Haider for blaspheming against their God. Haider’s poem was written from a place of very deep despair by a young man who had seen first-hand what men could do to men in the name of their God:

‘I met the liar [a prophet],

the fraud [another holy prophet]

and the rascal [a third prophet] who is full of politics.’

For a number of reasons — and, yes, our laws against causing religious offence are one of them — I’m not naming the prophets Daud listed. That isn’t the only reason, though: To me, the names aren’t the important thing in that poem.

Welcome to this episode of ThePrint Explorer.

For days now, Indians have been watching the violence that surrounded the collapse of Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina Wazed’s government and wondered what it might mean for her country and for ours. There’s been deep concern among other things about violence targeting Bangladeshi Hindus and whether Islamist groups will be able to feed on the chaos to find their way back to power.

50 years ago, Daud was arrested by President Mujibur Rahman’s government, tortured in custody, and then forced into exile. The Islamists who attacked him and even killed one of his cousins were never punished.

Daud was sheltered in India for some time like the much more famous Taslima Nasreen, quietly protected by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government. And then, he was given asylum in Germany.

The story has been completely forgotten except by a handful of writers and historians, which is I guess a good thing because Daud quietly visited India several times without sparking off the kind of Islamist protests that have prevented Salman Rushdie from returning to his ancestral homeland.

Ever since 1971, Indians have been conditioned to think of Bangladesh as a battleground for two diametrically opposed ideologies: the secular nationalism represented by Sheikh Hasina and the Islamists. Daud’s story though teaches us that things were and are considerably more complicated.

Less than three years after the sunrise of a new secular Bangladesh, Daud’s story teaches us its government was being forced to increasingly make ugly compromises with religious chauvinism.

Following Mujibur’s assassination in 1975, there was genuine support for regimes that made peace with the 1971 jihadists, even putting them in positions of power and authority. And Mujibur’s daughter Sheikh Hasina Wazed would make her own unscrupulous accommodation with religious fundamentalism.

Also Read: Why China accessing Sea of Japan through Russia-North Korea border river can ring alarm bells

The path to Partition

Like much of what we today call South Asia, Bengal was a crucible for competing identity movements before and through the colonial era. Historian Dilip Kumar Chattopadhyay tells of how the Faraizi and Wahhabi movements of the 19th century used religion as a tool to mobilise the poor Muslim peasants in East Bengal against their mainly Hindu landlords, as well as the East India Company, of course, which sat at the top of the pile.

Among other things, these movements brought the peasantry together in rebellion against taxes and levies. To create an organised community of resistance, they used the symbols and practices of what we would today call Islamic neo-fundamentalism.

Faraizi and Wahhabi rebels were not surprisingly crushed by the East India Company’s forces. Together with the Hindu revivalists in Bengal, though, these movements laid the foundation for competitive communalism to become the main language of politics in the region.

To sharpen the cleavage, there were a long series of battles over issues like cow slaughter, which would often explode into savage communal riots.

George Nathaniel Curzon, whom you might have come across in school in some very boring history classes, Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, used these divisions.

In 1905, he partitioned Bengal between its Hindu majority West and Muslim majority East. Though the partition was revoked six years later amidst a storm of protest, a whole series of political interests had developed around the idea of a divided policy. These would eventually explode as we all know in 1947.

To many in Bangladesh, among them we know from his own remarkably candid memoirs, Mujibur himself, partition seemed like a good idea, a necessary idea. He just couldn’t imagine a secure future for Bengali Muslims in a Hindu majority country. Things began to unravel pretty soon though.

The Bengalis had dreamed of a land free from the economic domination of the Hindus, and they thought they would have a leading role in this as representatives of the majority of Pakistan’s citizens.

North Indian Muslim politicians, on the other hand, had pictured themselves as the natural leaders of Pakistan because they considered themselves to be the guardians of the Muslim renaissance which had birthed the two-nation theory. Following independence in 1947, many North Indian Muslim politicians were very uncomfortable with Bengali identity, and language rapidly became a battleground.

Historian Amina Mohsin records the Education Minister of Pakistan giving this speech, and it’s worth listening to carefully. ‘Not only Bengali literature, even the Bengali alphabet is full of idolatry,’ he wrote. ‘Each Bengali letter is associated with this or that God or Goddess of the Hindu pantheon. Pakistani and Devanagri script cannot coexist.’

To ensure a bright and great future for the Bengali language that Minister Fazal Elahi Chaudhry wrote, ‘it must be linked up with the Holy Quran.’

And that link-up was obviously through the Arabic script. The model the minister may have had in mind was not just Urdu but likely his native language Punjabi, which had used the Persianate Shahmukhi script together with Gurmukhi for centuries.

Pakistan’s first prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan had the same ideas about Bengali but with a more explicit linguistic model in mind.

He said, I quote, ‘Pakistan has been created because of the demand of 100 million Muslims in this subcontinent and the language of 100 million Muslims is Urdu. It is necessary for a nation to have one language and that language can only be Urdu and no other.’

Now this was a pretty bizarre thing to say as plenty of people have pointed out. Urdu was, in fact, spoken by just 3 percent of the population of Pakistan. So to put it politely, the prime minister had a poor grasp of facts.

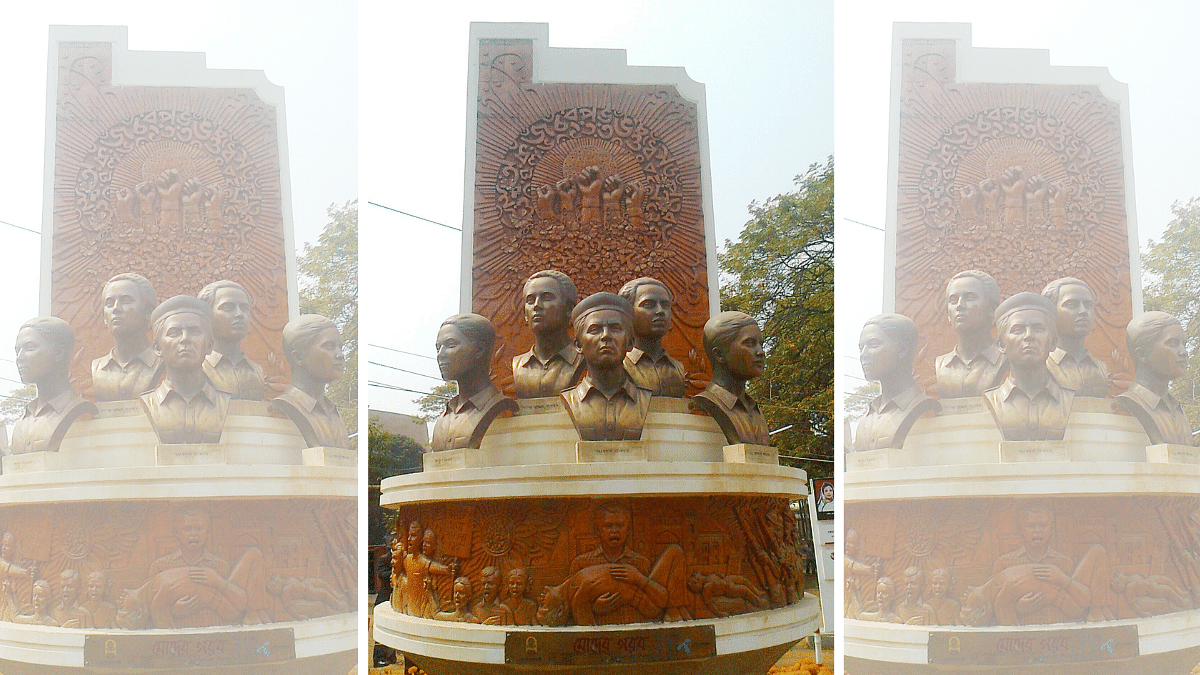

Things came to a head in 1952 when students of Dhaka University protested against plans to make Urdu the official language of Pakistan. There was violence and five people, including a nine-year-old child, were killed on 21 February that year.

The protesting students brought about a profound generational rupture with the two-nation movement, a period. The idea of Pakistan itself seemed to be dying. Even though Bengali was eventually accepted as an official language in 1956, Pakistan’s military rulers kept trying to push Urdu through the back door.

General Ayub Khan, historian Yasmin Saikia recorded, had a secret manifesto crafted in 1961 which outlined measures to use compulsory religious education to Islamised East Pakistan. Bengali history was rewritten with an emphasis on the Arab roots of Islam.

All of this of course ended up backfiring. The Muslim League, which had shepherded East Pakistan towards partition, rapidly lost all legitimacy, not only because of the language issue, but economic mismanagement.

The stark economic contrast between East and West Pakistan really enraged many in East Bengal. To many in the province, it seemed that the relationship between the two wings of the country was colonial rather than a partnership.

Also Read: How Pakistan got the nuclear bomb & then walked away from a peace deal

An ambiguous secularism

Islam could no longer hold things together as Pakistan would discover in 1971. This background forms the foundations that Bangladesh was created on the back of a secular struggle.

True, there is plenty of evidence to support this thesis. The 1972 constitution of Bangladesh made a firm commitment to secularism and the right of all religions to equal treatment. There is no doubt at least in my mind that Mujibur meant it.

Secularism wasn’t just an empty promise at that stage. Early on, Radio Bangladesh dropped the practice of beginning its broadcast with Quranic verses, replacing them with a multi-religious programme called ‘Speaking the Truth’. Hindu religious festivals began to be covered on radio just like Islamic ones.

And yet, we have to ask the question, what exactly did secularism mean? In 1969, just two years before independence, when the Awami League last stood for elections in an undivided Pakistan, it promised it would ensure no laws were enacted which were opposed to the Quran and the traditions of the Prophet called the Sunnah.

This was the manifesto on the basis of which the Awami League won a landslide electorally in 1970. We’ll never know what might have happened if Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto hadn’t persuaded the army to ignore the democratic verdict in favour of Mujibur, tilting East Bengal into outright rebellion.

From 1952 on, the Awami League also fought elections in alliance with various Islamist-leaning parties like the Nizami Islam and the even more hard-line Khilafat-e-Rabbani. And soon after independence, it became clear to Mujibur that he had a real problem with resistance to his secularist ideas.

Now, if you think about it, there was a real problem here. If, as Bengali secularists proclaimed, the two-nation theory was dead, why was Bangladesh a separate country instead of assimilating with West Bengal? What was the case for a new nation, a Muslim-majority nation, to exist at all?

Mujibur had to repeatedly clarify that he was not against religion and his notion of secularism was not anti-religious. That meant he was soon forced to roll back his own early secularism.

In 1973, Mujibur declared a general amnesty for all prisoners, including Islamist leaders and rank-and-file killers who collaborated with the Pakistan military. The recitation from religious texts in state, radio and television were resumed. Government grants for madrasas were dramatically increased, and the study of Islamic subjects was made compulsory in secondary schools.

The Islamic Academy that Mujibur had earlier abolished because of the reactionary ideas it peddled was revived under a new brand name in 1975. Gambling and consumption of alcohol by Muslims were banned. And of course, Daud, not his attackers, were arrested by the Criminal Investigation Department, then tortured in an effort to make him confess to being a CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) agent.

Foreign policy also saw the emergence of new Islamic alignments, turning Bangladesh away from India and the Soviet Union. In February 1974, Mujibur joined the Organisation of Islamic Conference (OIC) at a meeting held in Lahore. Soon afterwards, Bangladesh joined the Islamic Foreign Ministers Conference in Kuala Lumpur and became one of the founding members of the Islamic Development Bank.

To some experts, all this suggests that civil society in Bangladesh, unlike Mujibur and some of his allies, just wasn’t ready for the kind of secularism the Awami League wanted to bring.

Another less charitable hypothesis is that Mujibur was trying to shore up his flagging support by using religion. There was a terrible famine in 1974, inflation was out of hand, and the price of rice far exceeded its level under Pakistani rule.

Endemic corruption and pillaging of resources by the powerful Awami League politicians stripped the fledgling government of its legitimacy among the masses.

Islam & the Army

Fifteen years of military rule would see official Islamisation steadily deepened. General Ziaur Rahman took power in 1977, two years after a coup carried out by junior military officers. The coup represented a reaction by the institution of the Bangladesh armed forces to Mujibur’s efforts to build up a party militia of 1971 veterans as a counterweight and private army.

To legitimise the army’s regime, Zia removed secularism from the constitution, as well as its prescription of communal parties and the abuse of religion in politics. This together with generous support for religious causes built the bridges between the army and the religious parties.

General Hussain Muhammad Ershad, who in turn evicted General Zia in a coup, declared Islam the state religion, which still stands today. He introduced measures to introduce mandatory Arabic and Islamic studies classes in both elementary and secondary schools, and ordered radio to broadcast the call to prayer for Muslims five times a day.

The general even tried to turn the Language Martyrs’ Day — remember the 1952 protests where students were shot — into an Islamic event by trying to get rid of barefoot processions at dawn and the display of traditional colourful paintings known as ‘alpana’.

Evidence exists that these measures were popular, reviled as they were by a section of the intelligentsia. The 1978 elections saw General Zia win a massive mandate for a five-year term. Khalid Zia, his widow, won elections by pushing further Zia’s policy of Islamisation and alliance with parties like the Jamaat-e-Islami and other elements of the religious right.

Yes, those elections probably were not scrupulously fair, but they were as good or bad as most others we’ve seen in Bangladesh and tell you something about the popular mood.

Like her father, Hasina came to power on a platform of secularism. She initiated war crime trials targeting the 1971 perpetrators and sought to purge the country of Islamists. The outlines of what she was trying to do are present in a paper co-authored by her son, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, and former American military officer Carl J. Ciovacco, which was published in November 2008 just before the ninth general elections in Bangladesh.

The authors laid out a plan to evict Islamists from the army, the administration, and the control of religious institutions. Even as she moved to crush jihadist groups, which were waging a massive campaign of violence and intimidation across Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina’s lieutenants also confronted religious reaction in society.

For example, addressing a workshop in 2009, law minister Barrister Shafique Ahmed said, I quote, ‘madrasas are turning into breeding grounds of religion-based terrorism’.

And at a roundtable discussion in Dhaka in 2010, the then deputy speaker of parliament Colonel (retired) Shawkat Ali spoke out against the hijab saying, I quote and I apologise for the misogyny of this language. ‘Only those who have ugly faces use religion to cover them.’

The same prime minister, who reinstituted secularism into Bangladesh’s constitution, though also claimed she would rule in accordance with the Charter of Medina, a seventh century agreement between prophets and the city’s Jews that granted minorities expansive protections but not equal citizenship.

Hasina also patronised the ultra-right Hefazat-e-Islam clerical movement, considering several of its religious demands, like giving madrasa-educated students the same status as college graduates. The work of some, mainly Hindu authors, were excised from textbooks.

Faced with attacks from jihadists, progressive writers, and bloggers were threatened with state action and sometimes forced out of the country. And little was done to actually punish the right-wing perpetrators of violence against Hindus.

Six years ago today, our colleague Xulhaz Mannan was murdered for being a vibrant light and fierce champion of diversity, equality and inclusion. We continue to honor his legacy by promoting human rights and building a more hopeful, just, and brighter future for all. pic.twitter.com/tW3YFmTBEI

— U.S. Embassy Dhaka (@usembassydhaka) April 25, 2022

That’s politics, you might say. Everywhere in the world, yesterday’s mass killers, rioters and arsonists end up becoming tomorrow’s respectable leaders. The United States even rehabilitated Nazis it knew were involved in genocide during the Second World War.

This episode isn’t about moral judgement. It’s about trying to understand why Bangladesh has ended up the way it did. For me, the real significance of the Daud story doesn’t lie in the reaction his poems provoked among Islamists. That was only to be expected.

But the Awami League’s secular establishment, you see, also turned on the young poet in ways which were very telling. They were protested by students at Dhaka University, Jahangirnagar University, and the Dhaka University’s Employees Association demanded his punishment.

Scholars Mubashar Hasan and Arild Ruud record that some students even wanted “atheism banned from the classroom” in 1974, less than three years after liberation.

Even progressive writers who might have been expected to defend Daud criticised him for offending religious sentiments. The Dhaka journalist union didn’t even object to his arrest. If they understand why they reacted in this way, we get to the heart of what is going on in Bangladesh today.

Easy as it is to cast it as a battle between secularism and an Islamist horde, or between Islamist attackers and Hindus. This is just one more phase in a deep and complicated contest for the soul of the country that began in 1971 but still hasn’t ended today.

I am Praveen Swami, and I am a contributing editor to The Print. Thank you for watching today’s episode of ThePrint Explorer.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Collapse of 2 ‘Urban Naxal’ cases shows panic & police overreach are worse than Maoist insurgency