New Delhi: Nearly a decade after the foundation for Delhi’s Kalkaji Extension slum rehabilitation project was laid, 3,024 flats for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) were inaugurated in the area by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 2 November.

This project is part of the Delhi Development Authority’s (DDA) larger plan to rehabilitate residents of 376 jhuggi jhopri (slum) clusters in accordance with the guidelines of the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY), a housing-for-all scheme launched in 2015 that had the goal of making Indian cities slum-free by 2022.

The Kalkaji Extension flats are an example of in-situ slum redevelopment (ISSR). This involves rehousing the former slum residents in multi-storey buildings — like the ones in Kalkaji — constructed in the same location in order to avoid displacing people and hurting their livelihoods.

ISSR is the most common of the four models, or verticals, that the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs follows in its drive to implement the PMAY.

Here’s how this slum redevelopment is being carried out in Delhi, and — with the implementation of the scheme varying from place to place — how it compares to efforts in other states and cities.

Also Read: Strict deadlines, amnesty, new developers — Uddhav govt’s plan to speed Mumbai’s slum projects

PMAY guidelines and ISSR

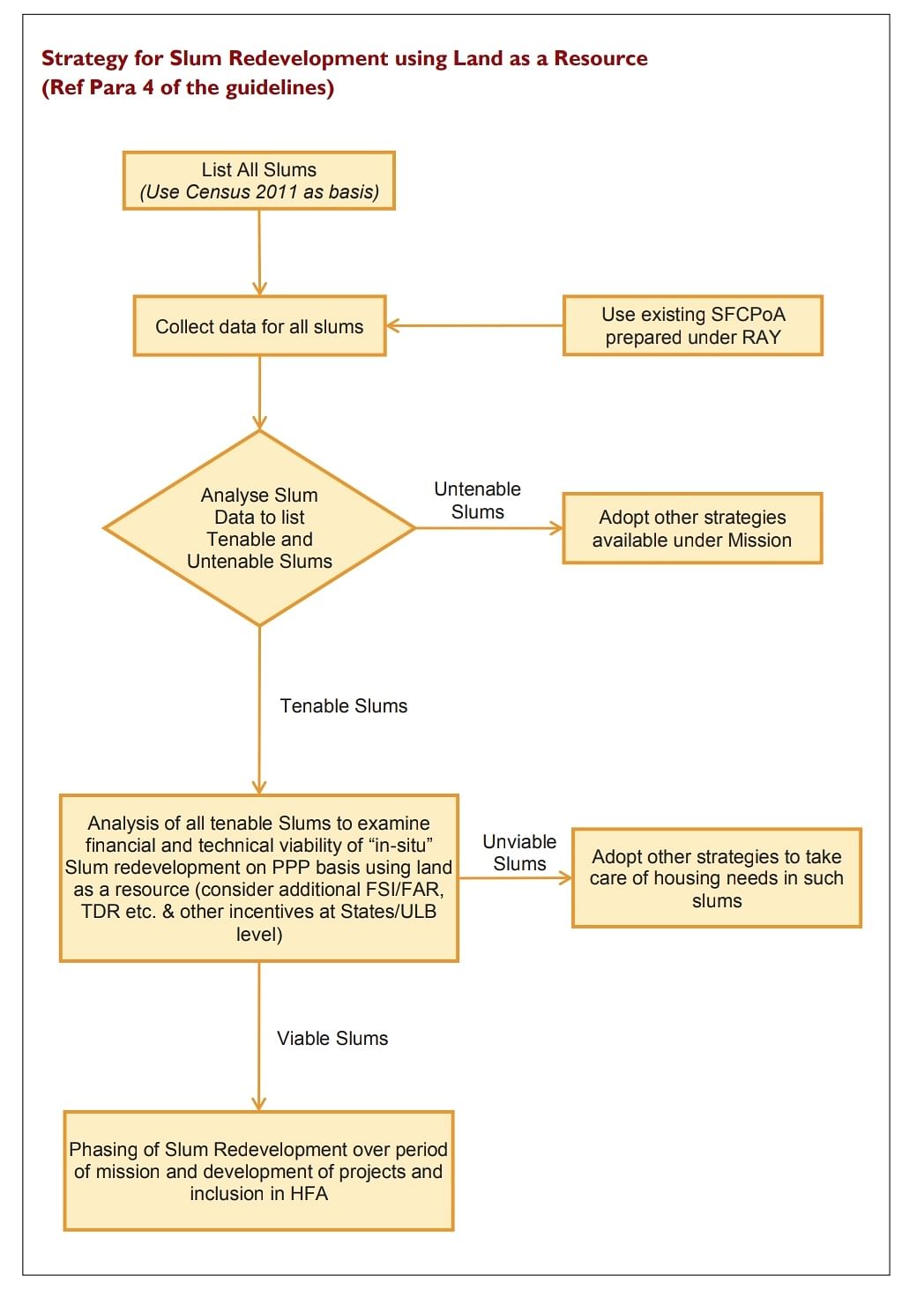

According to the PMAY guidelines, states and Union territories should first collect data on all the slums listed in the 2011 census, and categorise them as either “tenable” or “untenable”.

The Union government defines untenable slums as those near major stormwater drains, railway lines, major transport alignments, and rivers or water bodies, among others. These slums cannot be used for the ISSR model, but they are eligible for the other three verticals.

Tenable slums, on the other hand, ought to be examined for “technical” and “financial” viability. The viable ones will then be included in the PMAY-Housing For All (HFA) scheme for redevelopment.

Preferably, ISSR is done through the public-private partnership (PPP) model. While the private sector brings in finance and construction expertise, the public sector offers land for rehabilitation. The private developers are also liable to provide “transit accommodation” to eligible slum dwellers during the construction period.

ISSR projects have two components — “slum rehabilitation” and “free sale”.

The former includes housing along with basic civic infrastructure for eligible slum dwellers, and the latter is a section of flats that will be available to the private developers to sell in the market to “cross-subsidise” the project — in other words, to make a financial recovery. The DDA guidelines outline a 60 to 40 ratio respectively for these two components.

The ‘Delhi model’

In addition to the completed Kalkaji project, Delhi has ongoing slum rehabilitation efforts in Kathputli Colony and Jailorwala Bagh. While the latter is likely to be ready by December this year, the date of completion for Kathputli can’t be estimated yet, according to the DDA.

According to DDA housing commissioner V.S. Yadav, the Kathputli Colony project — first announced in 2008, but delayed for years — is currently being developed through a PPP model with Raheja Developers.

“…Kathputli Colony is being rehabilitated, it’s the private company handling the construction (that) will be expected to build flats for the residents in 60 per cent of total land (provided by DDA) and the rest 40 per cent will be given to them on a freehold basis to recover costs by utilising it for commercial purpose,” he had previously told ThePrint.

In contrast to this PPP undertaking, the Kalkaji Extension and Jailorwala Bagh projects were undertaken by the DDA itself. For the residents of Kalkaji extension, the DDA provided new homes were in the vicinity .

Nevertheless, these projects also come under the ISSR vertical. This is because they began earlier. The Kalkaji project was announced in 2011 and the foundation stone laid in 2013, all before PMAY was introduced — which meant the guidelines making PPP the preferred option for ISSR didn’t yet apply.

“The PMAY guidelines also add that if PPP is not feasible, other options may be explored if found economically viable by the landowning authorities,” explained Yadav.

Yadav had also added that for all the DDA’s future projects, the PPP model would be used. According to its annual budget for 2022-23, the landowning agency also plans to start six other in-situ slum rehabilitation projects, in the Rohini, Dilshad Garden, Shalimar Bagh, and Haiderpur areas.

How does it compare with other states?

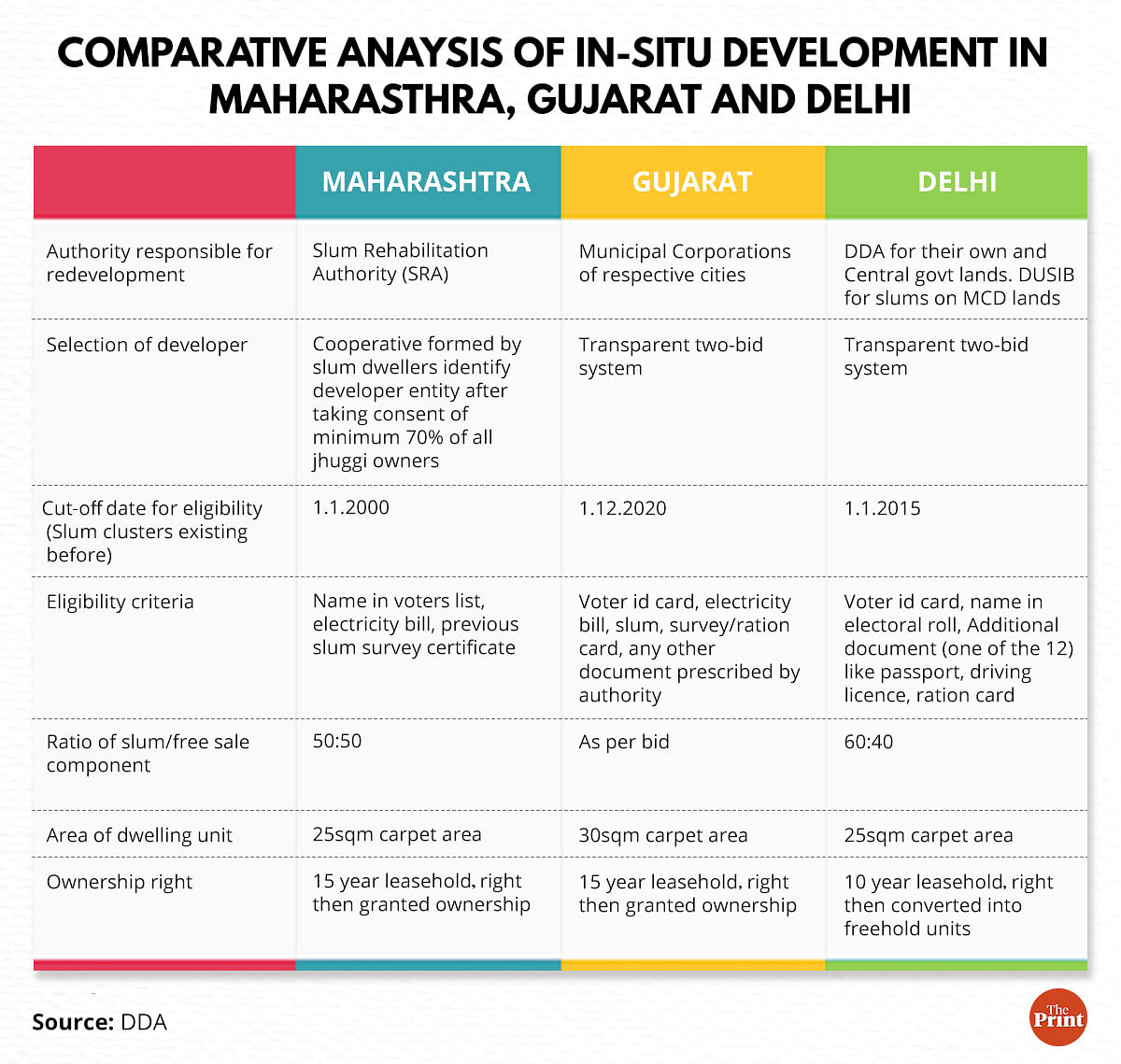

The DDA studied the implementation of ISSR in two other states — Maharashtra and Gujarat — to develop its own model, with officials visiting ISSR projects in Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Surat.

Under the policy followed by Maharashtra’s Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA), the developers — after getting the consent of 70 per cent of residents — submit a proposal to the SRA in association with slum cooperative societies.

The developer will pay a premium for land under slum encroachment at the rate of 25 per cent of the price of the property as decided by the state government.

The SRA pays 90 per cent of that money to the landowning agency — whether it’s the government or semi-government or local bodies — and keeps the remaining 10 per cent as administrative charges.

The SRA’s foremost project is the redevelopment of Dharavi.

In Gujarat’s Ahmedabad and Surat, in-situ rehabilitation projects have been undertaken under the state’s 2013 Slum Rehabilitation Policy.

It was also the first state to take up the PPP model for in-situ redevelopment of slums in urban areas under PMAY. The EWS flats were disbursed to the slum residents free of cost, unlike the projects in Delhi where the beneficiaries were charged Rs 1.42 lakh per flat.

As of 2020, 13 ISSR projects have been completed in Gujarat according to a report by NITI Aayog’s Development Monitoring and Evaluation Office.

Another factor here that differed from Delhi was that beneficiaries who owned shops in the slums would be allotted shops on the redeveloped land. Maharashtra also has a similar provision.

The Union government’s PMAY scheme has also been taken up by Tamil Nadu. The state government has designated the Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board, formerly known as the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board, as the mission directorate for the scheme.

Civic agencies such as the Greater Chennai Corporation have started identifying nearby land resources for the in-situ redevelopment of slums situated along waterways. Residents of these slums were formerly deemed encroachers, and attempts were made to evict and relocate them to rehabilitation houses on the outskirts of the city.

Also Read: Assam’s Miya museum closed ‘for being in PMAY house’, ‘What’s new there except lungi?’ says CM

Concerns across the country

Despite its quick adoption in several states, there have been many concerns regarding ISSR rehabilitation through high-rise buildings.

For instance, the Maharashtra SRA’s efforts have been criticised for allegedly being more “development-centric” than “pro-people”. Critics accused it of refusing to invest in projects project, giving prime real estate to private developers and being heavily dependent on them for implementation, while failing to ensure “good housing” for slum residents.

It has also been argued “vertical living” in high-rise apartments doesn’t suit former slum dwellers. It is said to restrict their community interaction, resulting in a negative impact on their social networks.

It also disconnects them from their means of subsistence, which is often dependent on access to streets. This, in turn, threatens the residents’ economic sustainability and micro-entrepreneurial opportunities.

Other concerns involve lacunae in the PMAY policy, where it has not been specified how untenable lands are to be managed. In Chennai, citizens’ groups thought that this could lead to the construction of more resettlement houses in the outskirts.

Other models of rehabilitation

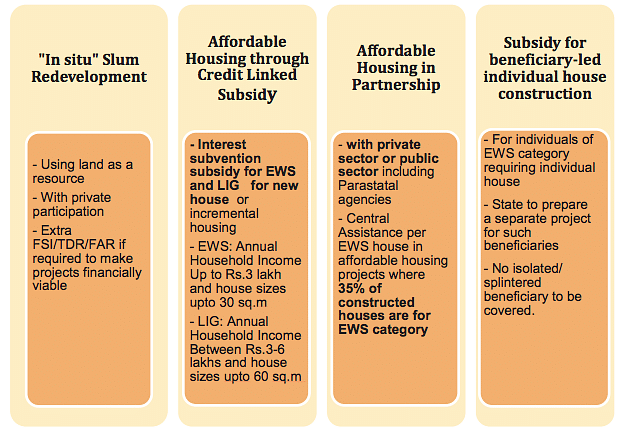

The three models of rehabilitation other than ISSR are the Credit-Linked Subsidy Scheme (CLSS), Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP), and a subsidy for beneficiary-led individual house construction/ enhancement (BLC).

CLSS is the only model that isn’t implemented by the government through local authorities. Under this, people in the EWS and Low Income Group (LIG) categories seeking housing loans — up to Rs 6 lakhs from banks, housing finance companies and other such institutions — would be eligible for an interest subsidy at the rate of 6.5 per cent for a period of 15 years, or during the period of the loan, whichever is lower.

This loan must be for new construction, or the addition of rooms, kitchens, toilets, etc to existing dwellings as incremental housing.

Under AHP, the government extends concessions to private developers such as tax subsidies, land at affordable cost and stamp duty exemptions to incentivise them to build 35 per cent of their total residences for the EWS category.

The state or Union territory then decides on an “upper ceiling” on the sale price of EWS houses in order to make them affordable and accessible to the intended beneficiaries.

BLC involves beneficiaries approaching urban local bodies (ULBs) with adequate documentation regarding the availability of land owned by them. On the basis of these applications, ULBs ensure that the proposed houses are constructed in accordance with the city’s planning laws. They also make sure that the finance needed for construction is available to the beneficiary from different sources including their own contribution, and the central and state governments.

PMAY’s predecessors

There have been comparisons between the PMAY and an already existing programme, Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY), launched in 2009 by the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government.

While both had similar objectives of “housing for all” and making India “slum-free” and by 2022, the PMAY is more decentralised in financing development.

RAY also involved a larger role for the Union government, which bore 75 per cent of project costs. The state governments took on most of the remaining cost, with the beneficiaries having to pay very little.

Both schemes had policies for in-situ degradation and in-situ redevelopment or relocation.

Rajesh Sinha, a member of the national advisory board at the India Centre for Policy Research and Development, a New Delhi-based think tank, said RAY’s lifecycle was coming to an end when it was subsumed by PMAY in 2015.

Before RAY, in 2005, there was the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) — a mission to improve infrastructure and the standard of living in cities.

Basic Services to Urban Poor (BSUP) and Integrated Housing and Slum Development Programme (IHSDP) were part of JNNURM, which Sinha described as a “slightly broader” scheme as it also included components such as urban transport.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Also Read: From yoga to Slumdog Millionaire, Delhi govt hosts 1st ‘slum festival’ for night shelter residents