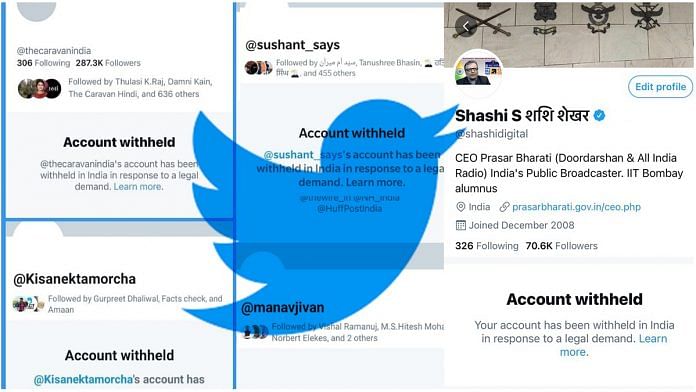

New Delhi: Twitter India Monday withheld several accounts for allegedly making “fake, intimidatory and provocative tweets” with hashtags accusing the Narendra Modi government of planning farmers “genocide”.

Among these accounts were English handle of news outlet The Caravan, actor Sushant Singh, farmers’ organisation Kisan Ekta Morcha and Aam Aadmi Party social media team member Aarti Chadha. A total of 250 tweets/accounts were withheld, but now all of them have been restored.

News agency PTI Monday quoted sources as saying that “incitement to genocide is a grave threat to public order” and that’s why Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) ordered blocking of these Twitter accounts and tweets under Section 69A of the Information Technology Act.

Reports also suggested that Twitter had blocked the accounts on the request of the Ministry of Home Affairs and law enforcement agencies to prevent any escalation amid the ongoing farmers’ protest.

This is, however, not the first time such a step was taken under Section 69A.

In February 2019, Jio users were reportedly unable to use sites like Indian Kanoon, Reddit and Telegram — all of which were blocked on government orders under the same section.

Also in June last year, 59 Chinese apps, including TikTok, UC Browser and Cam Scanner, were blocked under this section after the deadly Galwan clash between Indian and Chinese troops in Ladakh.

Also read: How India bans apps, can ban be beaten? All you want to know about govt’s China app ban

What is Section 69A?

Section 69A of the IT Act, 2000, allows the Centre to block public access to an intermediary “in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognisable offence relating to above”.

According to the definition under Section 2(w) of the IT Act, an intermediary includes “telecom service providers, network service providers, internet service providers, web-hosting service providers, search engines, online payment sites, online auction sites, online marketplaces, cyber cafes etc”.

While Section 69A provides the government the power to take such steps, the procedure to do so is listed in the Information Technology (Procedure and Safeguards for Blocking of Access of Information by Public) Rules, 2009.

“Any request made for blocking by the government is sent to an examining committee, which then issues these directions,” Apar Gupta, lawyer and executive director of the NGO Internet Freedom Foundation, told ThePrint.

However, Gurshabad Grover, senior researcher at the Centre for Internet and Society, underlined that in case of an emergency situation, such orders are passed by the committee’s chairperson first and then presented to the committee.

While no time is given to the stakeholder to respond before the action is taken in the case of an emergency situation, Rule 9 of the IT blocking rules allows for a review committee to send “recommendations regarding the case, including whether it is justifiable to block the accounts” in order to uphold the blocking of an account permanently.

However, it is Rule 16 of the IT Blocking Rules — which states that requests and complaints to block accounts must remain confidential — that has been repeatedly criticised for being “unconstitutional”.

Also read: Modi govt blocked 2,388 websites in 2018, stopped collecting data of arrests under 66A

Shreya Singhal v/s Union of India judgment

The striking down of Section 66A of the IT Act — under which posting ‘offensive’ comments online was a crime punishable by jail — by the Supreme Court in 2015 was hailed by many, but mixed feelings have remained. While Section 69A was also challenged, it was upheld by the court.

Law professor Chinmayi Arun had noted that while the SC “read down parts of the law to ensure that non-governmental parties cannot easily remove online content by force, it has left the process followed by the government to block content largely untouched, with only a few statements that might force a little improvement in the system”.

Drawing a comparison with another censorship law, sections 95 and 96 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), Grover told ThePrint, “Everything is in the public domain about how state governments can ban publications and persons. (Section) 96 even entails how one can challenge the order in a high court.”

These points were raised by the petitioner in the Shreya Singhal case, but the SC found little merit in it and instead noted how Section 69A is “narrowly drawn and had sufficient procedural safeguards.”

Section 95 of the CrPC talks about the “power to declare certain publications forfeited and to issue search warrants for the same”, while section 96 allows for an “application to the High Court to set aside declaration of forfeiture”.

Under Rule 16 of IT blocking rules of 2009, public disclosure of the request made for blocking and the actions taken thereof is not allowed.

“This has been interpreted by the government to prevent it from disclosing any blocking requests. This provision is unconstitutional. Under the Anuradha Bhasin v/s Union of India judgment, the Supreme Court had said that when access to the internet is restricted, reason must be given,” Gupta told ThePrint.

The judgment in the Anuradha Bhasin v/s Union of India case — which challenged the implementation of section 144 and communication blockade in Jammu and Kashmir — stated that “government-imposed restrictions on the freedom of expression and assembly must be made available to the public and affected parties to enable challenges in a court of law”.

“This rule is impacting fundamental rights such that it goes beyond the right of the author, editor or publication. For instance, withholding The Caravan’s Twitter account also impacts its readers,” Gupta added.

Concerns over Rule 16

Right to hearing is another ground on which concerns have been raised.

Rule 8 of the blocking rules extends pre-decisional hearing to the content creator or originator.

“They will give a hearing to Twitter, instead of the creator and Twitter has no incentive to challenge the order. In fact, if Twitter doesn’t comply, it is at risk of being fined and even jailed,” Grover noted.

“What we have seen in the past is whenever we file an RTI, the ministry rejects it on grounds of Rule 16. We have very little in terms of accountability and there is no parliamentary or judiciary oversight. Essentially, it is enabling opaque censorship,” he added.

For example, Tanul Thakur — creator of a satirical website blocked in September 2018 under Section 69A — was not given blocking orders even after publicly claiming ownership.

The Internet Freedom Foundation is currently fighting the case for Thakur, also a film critic, where it is challenging “the confidentiality requirement under Rule 16 and seeks a clarification that creators of content must be provided access to blocking order”.

Also read: Can Chinese apps appeal India’s ban? Section 69A of IT Act has the answer