Today is the anniversary of the first sepoy mutiny that took place more than 50 years before 1857 rebellion.

New Delhi: Although overshadowed by the First War of Independence in 1857, the Vellore mutiny of 10 July, 1806, was among the first uprisings against British rule in India.

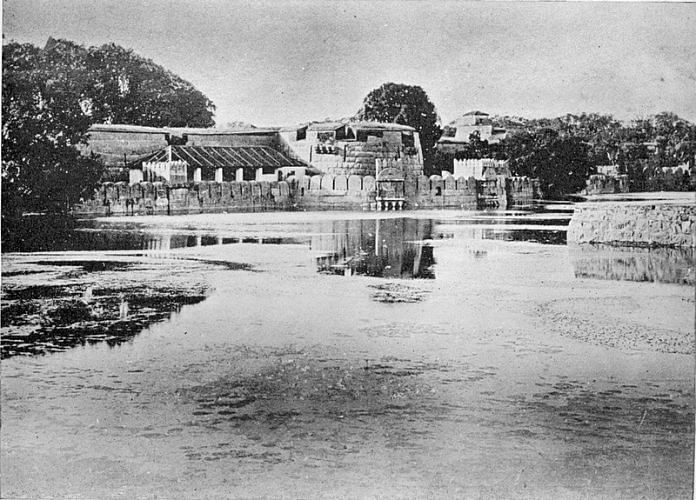

The one-day mutiny, mainly confined to the ramparts of the Vellore fort, saw native troops kill close to 130 British officers and soldiers, while losing close to 100 mutineers in the fighting.

According to historian Manu S. Pillai, the mutiny had a deep impact on the psyche of the British. “Vellore was proof of the fact that they could never be complacent in India, and until 1857, we often find Vellore being cited by officers as evidence that British might in India was less sturdy than it looked,” he told ThePrint

An early morning raid

The mutiny began in the early hours of the morning, taking the British troops by surprise. In his book Tiger of Mysore: The Life and Death of Tipu Sultan, Denys Forrest notes that the armed Indian sepoys attacked the small European garrison of four companies of the H.M.’s 69th and their own English officers. “The colonels of the 69th and of the 23rd Native Infantry were murdered, along with eleven other officers and eighty-two NCOs and privates,” Forrest wrote.

Among the first to be shot dead was Col. Fancourt, the commander of the fort and garrison. “Informed that the troops were in mutiny, the British commander went out of his door in his dressing gown, confident he could get them to fall back into order. Instead, he was shot. It was a wholesale massacre; few British officers and civilians survived (and some did by playing dead). Finally, British troops from Arcot blasted their way into Vellore and hundreds of sepoys lost their lives in retribution. There was no trial or court-martial at the time, just immediate execution,” Pillai said.

The British troops from Arcot were led by Colonel Robert Rollo Gillespie, who played a key role in quelling the mutiny. For his actions, Gillespie was immortalised by British poet Sir Henry Newbolt in his poem, Gillespie:

‘The Devil’s abroad in false Vellore,

The Devil that stabs by night,’ he said,

‘Women and children, rank and file,

Dying and dead, dying and dead.’

Without a word, without a groan,

Sudden and swift Gillespie turned,

The blood roared in his ears like fire,

Like fire the road beneath him burned.’

The uniform issue

Though there were several factors that sparked the resentment against the British, which included missionary polemics and payment of wages, the Indian sepoys were particularly miffed by the British East Indian Company’s decision to change the dress code for Indian soldiers.

In 1805, General Sir John Craddock, the commander-in-chief of the Madras Army, made it mandatory for the Muslims to shave their beards, trim their moustaches, while prohibited Hindu soldiers from wearing any kind of religious marks on their foreheads.

Further, the British government made it compulsory for all Hindu soldiers to wear a round hat replacing their traditional turbans. The new regulations hurt the religious sentiments of the soldiers, adding to the resentment. “The uniform issue mattered in that the British officers wanted soldiers to do away with caste and religious marks on their bodies and to wear standard uniforms. The new turbans sent out in summer 1806 had cow-leather and pig-skin cockades, for instance,” says Pillai.

The punishment for objecting to the new uniform was also cruel and angered the sepoys. “When some soldiers objected, they were dragged off and punished with between 500 and 900 lashes. As early as June, soldiers were plotting an armed response to this. Senior officers in Vellore were hearing rumours but decided to ignore the warnings. They could not comprehend how uniforms could cause such resentment. But since it touched on caste, religion, and matters of identity, Indian soldiers were fuming.” adds Pillai.

Role of Tipu Sultan’s son

Another factor that the mutineers took into account was the presence of Tipu’s family in the fort. They had been brought to Vellore by the British and housed in the fort after Tipu’s death in May 1799.

In one of the parallels with the 1857 revolt, the mutineers raised the Mysore flag and tried to prop up Tipu’s son Futteh Hyder as their ruler. He, however, did not turn up to support the warring Indian sepoys. “He stayed indoors and did not participate, even as the Mysore flag was raised and attendants and supporters of the Mysore prisoners in Vellore fraternised with the rebels,” Pillai says.

“There was also a wedding in the Mysore family on the eve of the rebellion, and the general noise, activity, coming and going of people appear to have been utilised by the soldiers plotting the mutiny. Perhaps Hyder was aware of what was about to come, but decided not to openly bless the event,” he adds.

The aftermath

The British played the rebellion as a plot to restore Mysore rule, obscure their own failings and lack of respectful communication with the Indian troops they commanded. It made more sense to claim there was a grand conspiracy rather than admit that issues of uniform, pay, and religious and racial prejudice, are what led to a violent outburst.

The mutineers were also summarily executed and their bodies burnt in heaps. “Where the Europeans were ceremoniously buried, the Indians were thrown into dumps and burned together. As a rebellion, it failed, but even London (when news finally reached them the next year) was left shaken,” Pillai says.

Nevertheless, the Vellore mutiny was one of the first acts of resistance against the British.

Very interesting piece of history.

Good article.

Good article.It enhansed our knowledge of history.

A very good article.it enhansed out knowledge of history.