Jind/Hisar/Rohtak: A small, cloth-wrapped bundle lay still and silent in the scorching midday sun outside a community centre in Haryana’s Rohtak. Passersby noticed her just in time and called the police. Just three days old, the nearly lifeless baby was rushed to the hospital. Two weeks later, her parents remain unidentified, but their motive seems clear—they didn’t want a girl child.

In another part of Rohtak, another baby’s story unfolded differently. Some months ago, Pooja Soni, 28, confronted an impossible choice—either abort her female foetus, or fend for herself with no job, educational qualifications, or resources. She chose the latter, leaving her two older daughters behind. The price is heavy, but she couldn’t bear to kill her baby, now a chubby six-month-old.

The words “Bholi Pooja” are tattooed on the young mother’s left arm. “I got this tattoo after I conceived. We were all very happy,” she said. But after she was ‘tricked’ into a pre-natal diagnostic test (PNDT) for gender, the fights and beatings began. Her right arm still bears the scars of iron burns, allegedly inflicted by her mother-in-law after she refused an abortion.

Travelling through Haryana’s districts, it’s impossible miss the “Save the Girl Child,” “Right to Birth,” and “Female Foeticide is a Crime” messages—whether on signs near traffic stops, shopfronts, or graffiti on walls.

But ‘Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao’, the scheme launched in Haryana’s Panipat in 2015 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to tackle female foeticide and infanticide, has done little to curb the deep-rooted desire for sons. For many, it’s still Beti Hatao that prevails.

Despite laws and promises, the sex ratio in Haryana has dipped in recent years. While it improved from 876 girls out of 1,000 boys in 2015 to 914 as of March 2024, it dropped sharply from 942 in 2022 to 921 in 2023.

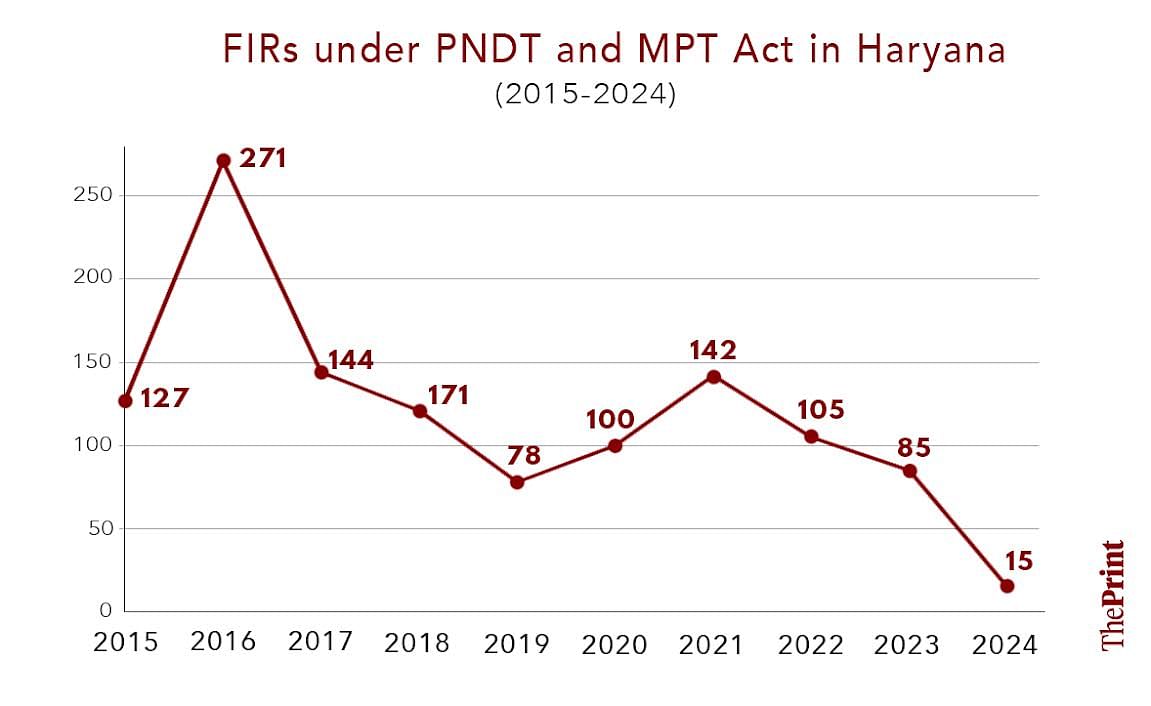

Data maintained by the Haryana Beti Bachao Beti Padhao team, exclusively accessed by ThePrint, reveals that in the 9 years until March 2024 only 1,189 FIRs were lodged under India’s anti-female foeticide laws— the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act and the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, aiming to prevent sex selection and illegal abortions respectively. This means that as many raids, including inter-state operations, were conducted in this timeframe.

Senior doctors, however, point out that this data might vary slightly from that of the police. MTP violations can be directly reported to the police by complainants, unlike PNDT violations which require a formal procedure. Additionally, MTP violations are often uncovered during PNDT raids, as illegal abortion materials might be found alongside evidence of sex selection.

An investigation by ThePrint also found that behind closed doors in homes and clinics, a horrifying trend thrives. The demand to eradicate female foetuses fuels a booming black market. Illegal sex tests and back-alley abortions flourish despite crackdowns. Facilitating it all are cheap, portable ultrasound machines from China, fly-by-night doctors, as well as nurses and others acting as touts for illegal sex-determination and abortion services. Many of these networks work across state borders to escape detection.

Throughout several villages in Haryana, set to go to polls on 25 May on all 10 seats, ThePrint met numerous women who are bearing child after child, suffering miscarriages, and risking their health just to have that one male heir in the family.

“The money involved is huge,” said a Haryana nurse who once moonlighted as a ‘tout’, speaking on condition of anonymity. “These things happen because people still want a boy. They get restless after having two girls. People are ready to pay in lakhs. Even the poor will sell anything for sex determination.”

Drop in FIRs, worsening birth rate

On the face of it, Haryana’s Beti Bachao Beti Padhao programme and its accompanying medical and legal machinery seem to be functioning robustly.

On-ground efforts are in full swing to implement the laws aimed to prevent sex selection and illegal abortions respectively.

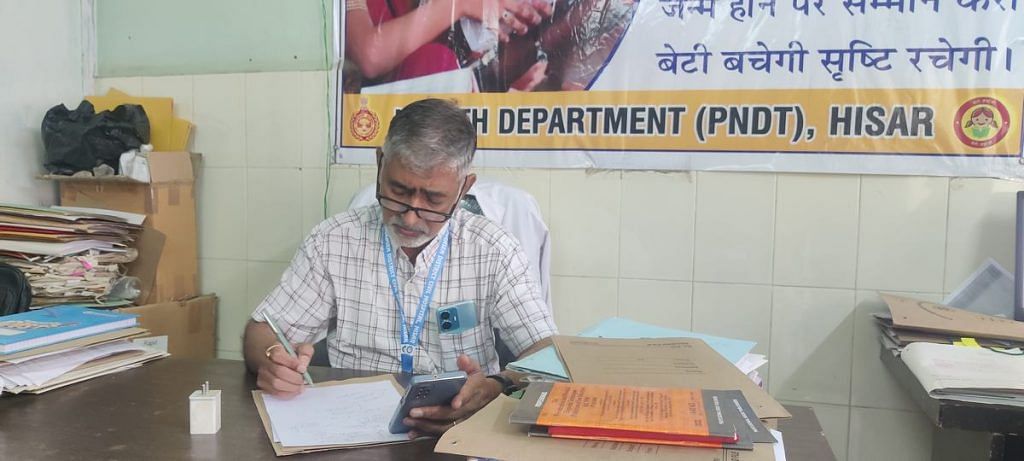

Doctors serving as PNDT nodal officers work to ensure that legal guidelines are followed, auxiliary nurse midwives and ASHA workers monitor pregnancies, while the Health and Education departments promote awareness and maintain oversight of ultrasound centres.

There have been efforts to crack down on illegal sex determination before, but they’ve become more systematic and effective since 2015, according to Girdhari Lal Singhal, Haryana project coordinator for Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao.

“There was no direct monitoring by the CM’s office before and only the health services managed everything. Fewer arrests were made before 2015, but since then an FIR is registered on every complaint and arrests take place. There is a set protocol now and a pattern is followed,” he said.

Singhal added that raids also now compulsorily involve pregnant women acting as decoys, making the outcomes more reliable.

However, the data on shows fluctuations, with a generally downward trend, in FIRs filed under anti-female foeticide laws. From a high of 271 in 2016, the FIRs under these laws went down to just 85 in 2023, and were at 15 as of March 2024. Meanwhile, the sex ratio in the region has been consistently falling since 2020.

According to Haryana civil registration data, accessed by ThePrint, the sex ratio varies across the state’s 22 districts. While the best performers are Charkhi Dardri (1055) and Fatehabad (993), the worst are Mahendragarh and Gurugram (both at 871), followed by Rohtak (879), Kaithal (886), Panipat (887), Jind (890), Faridabad (898), Rewari (900), and Hisar (911).

According to the World Health Organisation, the normal sex ratio at birth ranges from 930 to 980 females per 1,000 males. Anything below this range suggests the potential prevalence of sex-selective abortion or infanticide.

Why are there fewer raids now?

Doctors and health officials suggest that while ground-level enforcement has intensified, perpetrators of sex selection scans and illegal abortions have moved deeper underground. As a result, the flow of necessary tip-offs for raids has dwindled.

“The syndicates have changed their modus operandi and there are hardly any tip offs from secret informers,” said Dr Prabhu Dayal, the PNDT nodal officer in Hisar’s Maharaja Agrasen Civil Hospital, on the low number of raids. “Earlier, there would be only one tout (in a case) but now there are multiple, and the money trail is almost impossible to keep track of.”

Dayal also pointed to changes in the guidelines of the MTP Act after it was amended in 2021.

“Earlier, termination of pregnancies (from 12 to 20 weeks) required the advice of two doctors, but now it requires the advice of only one doctor. This essentially means that the chances of receiving information about illegal abortion have also decreased,” he said.

Lack of cooperation from women and their families is another hurdle, according to Dayal. Many pregnant women avoid registering with the ANMs even though it has to be “mandatorily” done within 12 weeks of pregnancy, which makes it difficult to track them.

“Even if we come to know of a case where abortion has taken place after sex determination, excuses are built up that the patient is unwell and (the pregnancy terminated) due to a medical condition. It is impossible to find out then that the termination is a result of the sex determination test,” Dayal added.

Unlike MTP Act violations, where police can act directly on a complaint, tackling illegal sex determination under the PNDT Act requires a more intricate process.

First, a formal complaint first needs to be filed with the “appropriate authority” (each state determines who this is) or an official designated as such by them. Subsequently, after a go-ahead from the authority, the police can conduct a raid with the help of a decoy. If evidence of illegal activity is found, the “authority” files the FIR.

Moving vans, Chinese machines & new hubs

When surveillance and crackdowns started intensifying, the shady world of sex determination in Haryana also evolved into what is now a full-fledged multi-crore racket, according to doctors and former ‘touts’ who spoke to ThePrint.

Gone are the days when gynaecologists, radiologists, and other doctors primarily performed tests in ultrasound centres and hospitals. Instead, many are now investing in new tools of the trade, such as tiny, portable, China-made ultrasound machines that cost about Rs 3-4 lakh.

The investment is not tough to recover. Each test costs more than Rs 50,000 and the price goes up if an MTP is part of the deal. Even MTP pills have become more expensive, with their cost doubling from Rs 500-600 to Rs 1,000 because of the clampdown.

“Nowadays, they conduct the tests even in moving vans and tiny makeshift clinics of jhola chhaps (quacks),” said Dr Dayal.

With scrutiny on hospitals and ultrasound centres ramped up, not moving with the times can come at a price.

Among those caught in the web of the law is well-known Hisar doctor Anant Ram, owner of the Anant Ram Janta Hospital, who is currently facing five pending cases under the PNDT Act, one as recent as 2023.

With his licence suspended and a previous six-month stint in jail for a sex-determination case, Ram has now swapped his doctor’s coat for a political role as vice secretary of Haryana’s Jannayak Janata Party (JJP).

While speaking to ThePrint, he denied all the allegations against him, while also arguing against the laws that ensnared him. Ram claimed that scrapping the PNDT Act might actually help tackle female foeticide since it would be easier to track pregnancies.

In February 2023, another doctor, radiologist Urmil Dhattarwal, once a Kaun Banega Crorepati contestant, was arrested after a raid at Hansi’s Dhattarwal Hospital for her alleged involvment in a sex determination racket.

The new modus operandi is both more nimble-footed and and secretive, involving a network of touts, cross-border contacts associated with various hospitals, lab technicians, and jhola chhaaps who navigate the system with a mix of old savvy and new technology. Some ultrasound operators have even migrated to neighbouring regions like Uttar Pradesh and Delhi to evade scrutiny.

“They take away the pregnant woman in the initial days to other states. The ANM or the health officials then can’t track them,” said Dr Gopal Goyal, chief medical officer of the Civil Hospital in Jind. “Ultrasound centres here no longer conduct these tests. Currently there are only 35 functional and certified ultrasound centres (in Jind) and they are constantly in our radar. Nowadays the tests are mostly being conducted in Delhi-UP borders and neighbouring areas.”

Facilitating these tests are a chain of “touts”, usually hospital staff or healthcare workers, who pass on strategic information until the illegal sex determination scan is conducted at a location that’s difficult for authorities to track.

“ASHA workers and ANMs, apart from nurses and hospital staff, also become touts because of the money involved,” Dr Dayal said.

While the ideal time for sex determination is after 12 weeks of pregnancy, some accused individuals are so well-versed with the process that they can determine the sex of the foetus even earlier, according to Haryana doctors.

To curb these illegal practices, Dr Ramesh Punia, a retired doctor now working as a social worker, called for stricter penalties under the PNDT Act. “Currently under the Act, the punishment only ranges from three to five years, with fines ranging from Rs 10,000 to Rs 50,000,” he said.

‘Abort, or don’t bother coming back’

When Pooja Soni got pregnant for the third time, her happiness was fleeting. She was already the mother of two daughters, and her husband and his family had no room for a third.

Early in the pregnancy, Dharmendra, her husband, took her far from their Rohtak home for a scan at a small clinic in Jagsi Village, Sonipat district. Only later did she realise the “doctor” was a quack and that the scan was to determine the foetus’s sex.

“The doctor did my ultrasound and my husband asked me to wait outside in the car. I asked him why didn’t the doctor ask me for my Aadhaar card and other details, which is usually the case. Then, he told me that he had done a sex determination test and that I am carrying a female foetus,” Pooja said.

The journey back home was probably Pooja’s longest car ride. Dharmendra delivered a chilling ultimatum, she said— “Ghar jaa ke abortion karwa ke aa iss bacchi ka. Nahi karwayegi toh wapas mat aana (Go home and abort this girl child, or don’t bother coming back).”

The 28-year-old felt lost and helpless, but she knew one thing — married women adjust and don’t leave their husband’s home. Married at 19 and afraid to bring shame to her parents, who had taken huge loans for her dowry, she stayed with her husband until she could no longer bear the pressure to abort.

“It isn’t as if he wouldn’t beat me up earlier but then he would apologise and we would have some good days as well. But after I refused to take the pill for abortion, the beatings increased They would starve me and make me do all the housework. One day, when I was seven months pregnant, he and his mother burnt me with iron,” Pooja said, showing her the marks on her hands and arms.

The incident last October became the breaking point. Finally, Pooja reached out to her brother, Manoj Soni.

Alarmed by her condition, he urged her to go to the mahila thana (women’s police station) in Rohtak, but it was only later that the family realised the gravity of what she had endured.

“When Pooja was changing, our mother saw burn marks on her body and we immediately rushed her to the Hisar government hospital,” said Manoj.

At the Hisar Civil Hospital, Dr Dayal promptly informed the Rohtak police about the situation. Following a raid on the clinic, the “jhola chhap” doctor and Dharmendra were arrested.

“She had courage to stand against all odds and fight for her child,” said Dr Dayal.

But back at her maternal home, Pooja, who has only studied, till Class 5 worries if she will ever get back her elder daughters, and how she will feed them if she does.

Women of Alipur

With buffaloes roaming its narrow lanes and men and women working together in the fields, Alipur appears like any other village in Hisar. But it holds the dubious distinction of having the district’s worst sex ratio—588 girls for every 1,000 boys, according to 2023 antenatal data for villages exceeding 5,000 people. In contrast, the district’s best performing village, Bhagana, boasts a ratio of 1515.

While Alipur’s skewed sex ratio concerns doctors across the district, staff at the village healthcare unit dispute any link to illegal sex determination or abortion. Dr Mahender (he does not use a surname) and several ASHA workers from the clinic maintain that the numbers simply reflect a higher number of male births in the village. They peg it to a fluke.

However, many of the women standing in the shaded courtyards or peeping out from windows have harrowing stories to share. No one speaks of foeticide, but they casually recount being trapped in a relentless cycle of pregnancy, ‘miscarriages’, and childbirth. Many accept this as their fate, a burden they must shoulder alongside household chores and farm work until they bear that one male child.

One 23-year-old resident, seven months pregnant, already has two daughters aged 3 and 4. She says she lost two pregnancies—one at two months and another at seven months.

“The child wasn’t getting nutrients and wasn’t growing. It was a girl child,” she said of the seven-month pregnancy. “The doctor said there was no movement and I had to abort.” The woman, who has been through all her pregnancies and births in just five years, also said she had low blood pressure and other health issues.

Similarly, a 30-year-old woman has four daughters, aged 9, 6, 3, and 9 months. “This time, my husband has told me we need a male child,” she says. “I want to stop giving birth, but what can I do?”

Nearby, another 26-year-old shares a similar story. Now six months pregnant, she too has four daughters, all between the ages of 1 and 5, born within seven years of marriage.

Sulochana, an ASHA worker in the village, claimed that the medical centre carefully keeps track of all pregnancies in Alipur.

“We note down all details within the first three months,” she said. “Even if they give birth at some other place and come back later, we record the birth too, including the sex.”

However, Sulochana acknowledges the difficulty in accurately documenting medical abortions and miscarriages.

“If someone lies or sends the woman to another village before we can note it down, and then she comes back after abortion, there is no way we can know unless the woman wishes to confide in us,” she added.

Dr Dayal also recognises the limitations of tracking clandestine medical abortions, unless complications like excessive bleeding require hospitalisation. Even then, answers aren’t guaranteed.

“When a woman is admitted due to excessive bleeding, it is our duty to first provide her with care and then ask questions,” he said. “There is no way you can prove that she has taken the pill unless she complains.”

Also Read: Broken sewage system, filthy ponds—Keorak, village adopted by ex-CM Khattar, ‘worse off than before’

(Edited by Asavari Singh)