Sonipat: Neelam Pahal first drove from Sonipat to Hisar city in a car and then to a remote village on a bike accompanied by a tout. Her purpose was to find out if she was pregnant with a girl or a boy. But she wasn’t going to a clinic or a hospital; she was headed to a field.

As Pahal lay on a cot, a quack ran his illegal palm-held sonography device over her belly, looked into his laptop and declared triumphantly: “It’s a boy.” Officials and police jumped into action and busted the operation, arresting the tout and the quack, and seizing the device. Four months later, Pahal, the decoy, gave birth to a girl.

Demand for gender determination tests in Haryana has sparked price wars in neighbouring Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, even though predictions are often wrong. Touts and operators offer to reveal the gender of a foetus using DIY palm-held sonography devices. Tests cost as little as Rs 10,000 in neighbouring states, and between Rs 50,000-Rs 1 lakh in Haryana. In February, the Chandigarh police conducted inter-state raids in Bulandshahr and Bareilly districts of Uttar Pradesh for offering sex determination tests to women in Haryana.

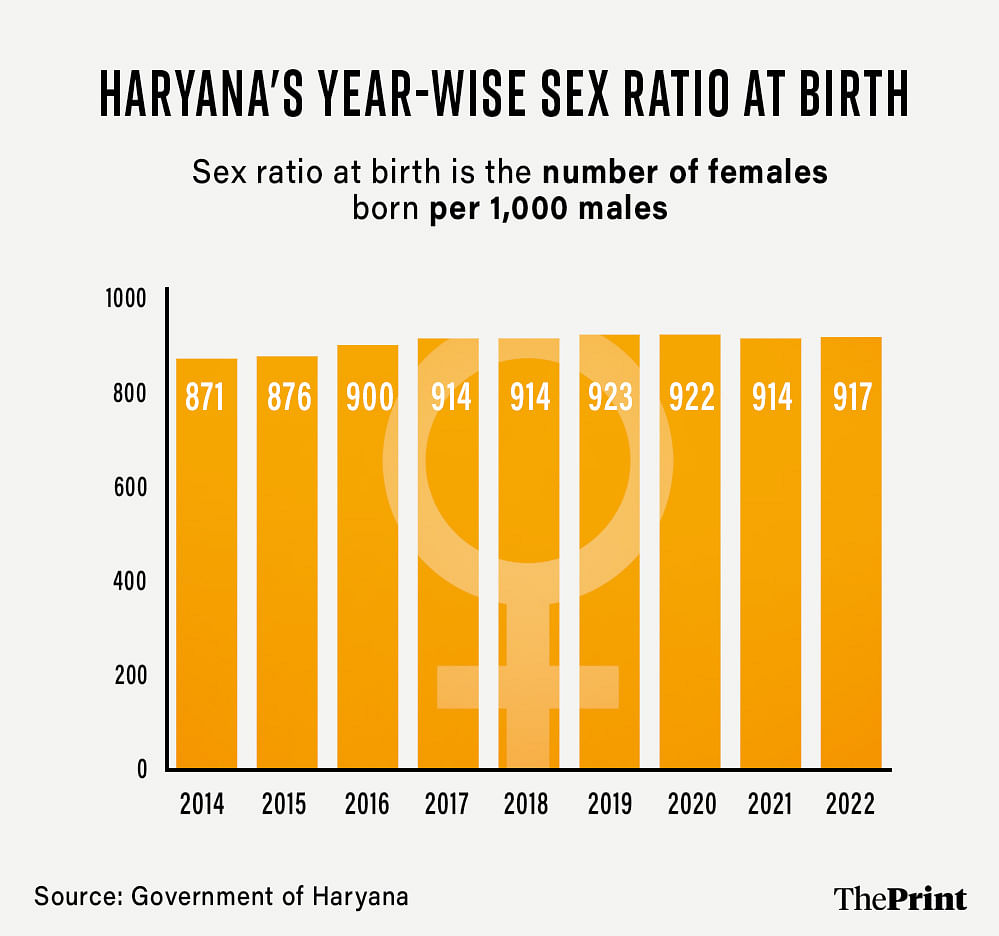

Haryana’s son-obsessed culture has fuelled a cottage industry, which is immune to legal bans. The Preconception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act 1994 have done little to stem demand. Haryana had recorded the lowest sex ratio at birth (SRB) as per the 2011 census, with 834 female births per 1,000 males.

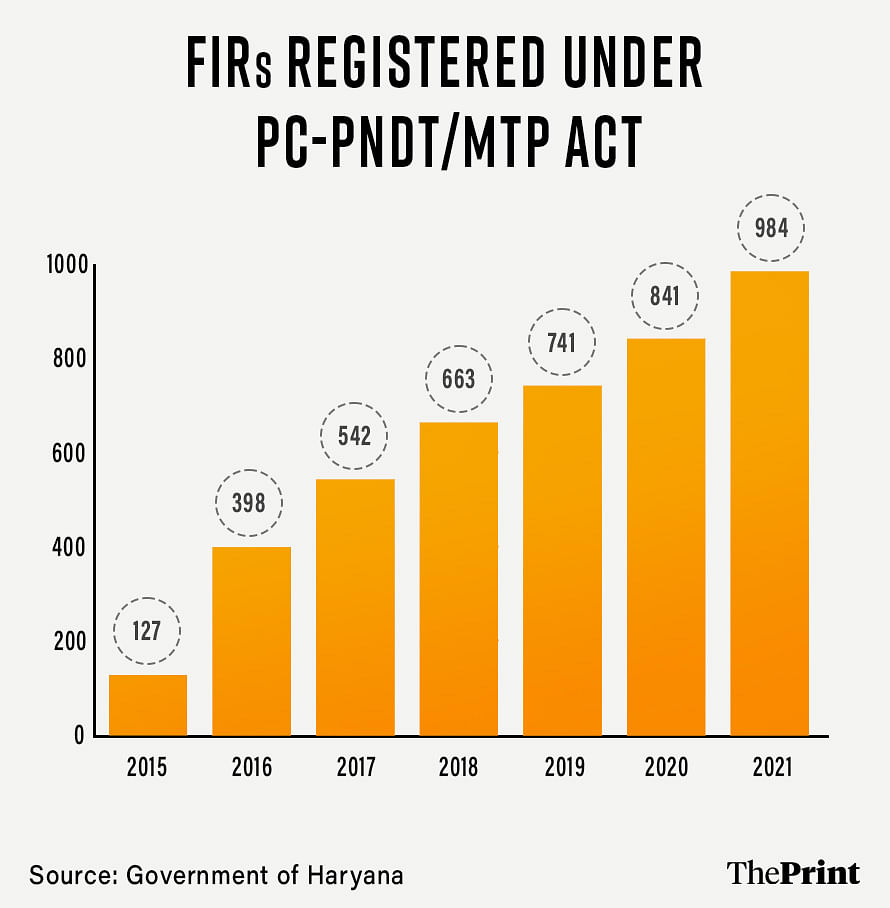

The ratio started improving after Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao campaign in 2015, but since 2020, there’s been a steady decline. Sex determination racketeers have upped the game, and special PNDT teams and police officers find themselves chasing ghosts.

“When we started the raids seven years ago, sex detection was done through fixed [sonography] machines. Now it has gone underground,” said Haryana’s Beti Bachao Beti Padhao convenor Girdhari Lal Singhal. Tests are carried out in fields, at isolated spots in villages, or at a relative’s homes, but never in clinics.

The skewed SRB, which has become a political issue, is playing out today with unmarried men buying wives from other states, a tradition colloquially known as ‘mol ki bahuein’. An unexpected fallout of this practice has been the emergence of ‘looteri bahus’—women who operate in gangs to dupe desperate men, running off after marriage with the family’s money and jewellery.

As a countermeasure, the police are increasingly relying on pregnant women to crack this nexus. And decoys like Pahal have become an important part of Haryana’s crackdown on illegal sex-determination rackets and female foeticide.

This urgency is fuelled by reports that Haryana’s sex ratio at birth has dipped by 11 points between January and May this year. In 2022, the state registered 917 female births per 1,000 males.

Decoys don’t come easy

With three children, all girls, 37-year-old Pahal is an expert decoy. The single mother from Sonipat aided the police through all her pregnancies, exposing over 30 sex determination rackets across Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan. Now, she works as an informer and helps new decoys.

Last year, President Droupadi Murmu met Pahal and commended her significant role in exposing sex determination rackets in Haryana. But at home, she is criticised and ridiculed by her mother-in-law and neighbours for giving birth to three daughters.

Last month, when her husband died of a heart attack, her mother-in-law attended the funeral only to berate her for not prioritising the family’s lineage.

“She said that now your husband is gone, the family lineage has ended and I would suffer without the son,” Pahal said.

She is committed to protecting the unborn girl child, but decoys like her are hard to come by. Most pregnant women are reluctant to join even though the Haryana government started incentivising them in 2015. Decoys are paid Rs 25,000 per operation, while informers receive Rs 1 lakh for correct information on doctors, nurses, and middlemen breaking the law.

When he got an important lead last year, Dr Gaurav Punia, a PNDT officer in Haryana’s Kaithal district, had no decoy. In desperation, he turned to his wife who was seven months pregnant. She agreed to be a decoy. Together, they travelled to Hapur district in Uttar Pradesh. For a fee of Rs 30,000, a tout took his wife on a bike to a nearby village where she was directed to a dingy one-room house, masquerading as a clinic. She was all alone, but Punia and his team were tracking her though GPS. They raided the ‘clinic’ and arrested the tout and the man who was testing her with the handheld ultrasound. He wasn’t even a doctor.

In another case in Alwar, Rajasthan, PNDT officers from Haryana successfully raided a set-up and arrested a handheld sonography device operator, Awdesh Pandey, for conducting a test on a woman from Rewari. Pandey had already served one-and-a-half years in jail and has seven FIRs registered against him. He used to pay a farmer Rs 500 to use his field. Pandey told the police that he got the sonography machine from Kathmandu, Nepal.

But not all raids are successful. More often than not, the informer is unable to give the exact location where the sex determination is being conducted. And touts and operators, who rely on their own network of informants, simply vanish when they get a whiff of police activity. Most operations are led by PNDT officers who are government doctors and dentists.

There are 22 PNDT officers, one for each district, who are empowered to call on the Criminal Investigative Agency (CIA) of the Haryana police to act on a tip. They are now under intense pressure to produce results.

“Before the Beti Bachao campaign, PNDT officers existed only on paper. But since 2015, they have been revitalised,” said an official.

The Haryana government started holding regular meetings with PNDT officials. Every month, a notice is served to districts with fewer successful raids or low SRBs.

On 1 July, the Chief Minister’s Office (CMO) served notices to seven districts, including Nuh, Bhiwani, Mahendragarh, Rohtak, Panchkula, and Sonipat for not performing expectedly in curbing female foeticide. Data from 2022 showed that Sonipat, Jhajjar, Kurukshetra, Faridabad, and Rewari were among the worst performing districts with SRBs below 900.

But the handful of overworked PNDT and police officers can barely keep up with the streetsmart operators and middlemen.

Untrained men, women

Sonu Bajaj’s claim to fame, and money, is through conducting sex determination tests in moving cars. As such, the raiding teams have a hard time pursuing him, said Singhal.

Bajaj, who is from Kurukshetra, is one of the most expensive illegal sex determination operators, charging as much as Rs 1 lakh. Although, he is known to offer hefty discounts to poor families.

“He has five FIRs against him in Punjab and Haryana. However, he has not been convicted even once,” said Singhal.

The individuals involved in the rackets are not doctors, but untrained, illiterate, and unemployed men and women looking to make a quick buck.

“They buy portable machines from China and Nepal, train for a month watching videos on YouTube, and then start taking on clients,” said a PNDT official.

Malkiat Singh from Punjab does not conduct sex determination tests in a moving car like Bajaj, but he is highly sought-after due to his accurate predictions. While he only came to the police’s attention in 2016, he has been involved in the sex determination racket since 2010. He travels to meet his clients in his Sedan Verna and has reportedly conducted tests in Kaithal, Ambala, Fatehabad, and Hisar. Currently, he has nine cases registered against him.

His business is driven by the families’ all-consuming desire for a boy child. According to Punia, most operators can’t even read the machines accurately, and give wrong information. PNDT officers from other districts agree.

“Families know they have been duped but they can’t complain because they are involved in something illegal,” said Vikas Saini, PNDT officer from Rohtak.

However, the low conviction rate means that most of these illegal operators spend little time in prison, usually not more than three months. Sanjay Sharma, a PNDT advocate from Jhajjar district representing the CMO, has prosecuted 80 sex determination cases in the past seven years but has only secured two convictions. Sharma attributes the low conviction rate to lengthy court proceedings and witnesses turning hostile.

“On average, a trial takes 2-3 years, which compromises the evidence. Often, decoys withdraw their statements because of societal pressure, and in other cases, the evidence is not strong enough to secure a conviction,” Sharma explained. The accused are typically detained for only 2-3 months before being released on bail and resuming their illegal rackets once again.

All for a ‘son’

The desire for a boy is all-encompassing. During the day, ASHA worker Reena from Kaithal spends hours talking to women about the importance of having girls. But the mother of three girls would return to her home in Batta village every day and pray for a boy.

“I knew that until I give birth to a boy, my husband would keep getting me pregnant. And I was done with multiple pregnancies,” said Reena.

During her third pregnancy, she recalls being partly unconscious when she heard the banging of plates to symbolise the birth of a boy. She was relieved, but the moment was fleeting. The noise stopped when someone confirmed that the newborn was a girl. In Haryana, a thali bajao (banging plates) ceremony is traditionally held to celebrate the birth of a male child and inform the entire village.

Four years ago, just four months after her third pregnancy, Reena became pregnant again, and this time she gave birth to a boy. Since then, she has not had any more children.

In Batta village, Ragini*, who is six months pregnant, is confident that she will give birth to a boy after undergoing a sex determination test last month. She walks proudly in the neighbourhood but finds it difficult to conceal her smile. To ward off evil, she lowers her dupatta to cover her face.

For Ragini, this is her fourth pregnancy. The last three times, she gave birth to girls, with one of them passing away shortly after delivery. All of her deliveries were done via Caesarean section, and the doctors have expressed concerns about the risks involved in the fourth delivery. But she is willing to take the risk in the hope of having a boy.

“This time, it will be a boy,” she tells her neighbour, while caressing her belly.

(*Name changed to protect the identity of the woman)

(Edited by Prashant)