For years, Indian liberals have fought for the right to freedom of artistic expression — the paintings of M. F. Husain, Jatin Das, movies like Fire and PK and readings of the Three Hundred Ramayanas.

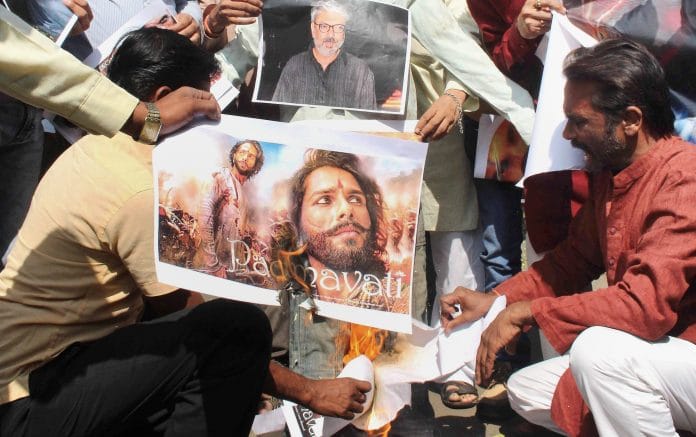

As calls rise for a ban on the release of Padmavati — a film that valourises Rajput caste identity and glorifies sati, we ask:

Is Padmavati forcing Left-liberals and feminists into an awkward silence on the question of unqualified freedom of expression?

The debate on the film Padmavati revolves around two arguments:

(a) The film is going to hurt the “sentiments” of Rajputs (read Hindus!) because it shows disrespect to “historical facts” and therefore, it should not be released.

(b) There is no “history” of Padmavati because it is a fiction and therefore, the sentiment argument is politically motivated. These claims are not entirely new — old Ahilyabai temple was destroyed to build the new Somnath temple in 1950s and Babri Masjid was demolished to reclaim the birthplace of Lord Ram in 1992 in the name of “Hindu sentiments”.

One may add Salman Rushdie and Taslima Nasreen episodes in this list, when sentiments of Muslims were given priority over history/fact/expression.

Here are other sharp perspectives on Padmavati and the freedom of expression:

Manish Tewari, lawyer, former UPA minister

Rohit Chopra, Associate Professor, Santa Clara University

Sabah K., journalist, ThePrint

Apar Gupta, lawyer

The Padmavati debate, however, offers us a possibility to work out a third position.

The term “freedom of artistic expression” is open to a variety of political interpretations. In this sense, the “Hindu sentiments” argument as well as “no fact no history” argument can legitimately be presented as imaginative articulations, which should be allowed expression.

The problem arises when these political interpretations are established as “ultimate truth”—closing all possibilities of further excavation of a story like Padmavati.

In fact, there is a shared assumption that common viewers/readers are not mature enough to draw their own meanings; hence, they need to be educated about their identifiable sentiment and/or factual history. This intellectual guardianship does not allow us to appreciate the intrinsic democratic impulse that transforms the freedom of expression into a moral-political value.

Therefore, there is a need to democratise the freedom of expression so that an open discussion (not debate) could be initiated on the contentious issues such as glamourisation of caste system and Sati practice in the name of Hindu pride. After all, stories are made to be retold!

Hilal Ahmed is an associate professor at CSDS