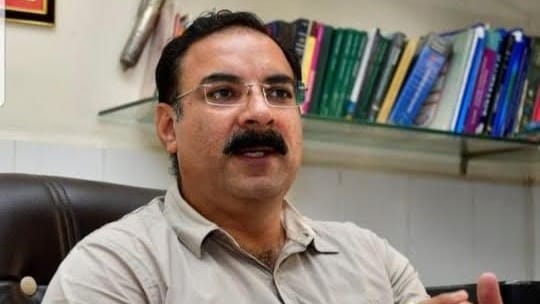

Dr Sandeep Bhola has got the state to treat drug addicts as patients and not criminals, and inspired a state-wide drive for de-addiction centres.

Chandigarh: In a state where drug addiction is rampant and governments tend to live in perpetual state of denial, this is the story of a government doctor working tirelessly, sometimes even in isolation, to deal with the scourge. His name is Dr Sandeep Bhola, and he is in charge of the Red Cross Drug De-addiction Centre in Kapurthala, as well as the Punjab government’s technical expert for ‘mental health and de-addiction programmes’.

Bhola is singularly credited with changing the approach towards drug addicts, getting the state to treat them as patients and not criminals. He has also managed to influence state policy in dealing with the menace. He believes that the government’s focus needs to shift from merely curtailing the supply of drugs to working intensively towards reducing the demand for them.

“While the former has been the responsibility of the law and order agencies alone, the latter supplements those efforts with contributions from the society and the community,” Bhola told ThePrint from Nepal, where he was invited to talk about the ‘reduction of harm from people who use drugs in SAARC countries’.

First experiment: Navjeevan

Bhola, who did his MBBS from Government Medical College, Patiala, followed by an MD in psychiatry from Government Medical College, Amritsar, worked in Punjab’s rural areas before taking over as the medical officer of psychiatry at Kapurthala Civil Hospital in 2006.

A year later, he started the ‘Navjeevan Drug De-addiction Centre’ in the civil hospital. Apart from providing OPD services, the centre also took in patients for detoxification and treatment.

This was 10 years ago, when the state government had not even begun to realise the magnitude of the problem, which would later become one of the biggest social health challenges facing the state.

At that time, the Kapurthala centre was the only government centre anywhere in the country to provide various drug de-addiction therapies under one roof.

Dr Bhola’s centre has since treated between 8,000 and 10,000 inpatients, apart from the thousands that have visited the OPD during these years. From a 15-bed facility in 2006, it has grown into a full-fledged 30-bed detox centre and another 50-bed rehabilitation centre.

“We ran Navjeevan professionally with the meagre funds which were available to us through the government, and yet we were able to do a good job. In 2016, the Navjeevan Kendra was conferred with the best non-profit institution award by the President of India,” Bhola said.

Also read: Punjab’s losing war on drugs as tough narcotics law is punishing, not reforming, addicts

State-wide policy

As the drug problem blew up in the Akali-BJP regime’s face in the run-up to the 2017 assembly elections, chief minister Parkash Singh Badal decided to replicate Bhola’s Kapurthala experiment across the state.

To bring about standardisation of facilities at the new centres, Dr Bhola was brought in to draft guidelines.

“These guidelines were important because it was for the first time that these facilities were to be provided by the government. There were several private drug addiction centres operating across the state, but the inmates complained of maltreatment,” Bhola said.

“There was an urgent need to formulate minimum standards, so that the government could start treating drug users.

“The quality of treatment you provide the addict needs to be cutting edge if it is to solve the problem. Eighty per cent of drug addicts relapse, so if someone has come seeking a solution, he should not be let down with poor facilities or lack of follow up.”

Dr Bhola was part of the nodal team that went on to set up a sturdy network of de-addiction centres across Punjab. Currently, there are almost 150 Out Patient Opioid Assisted Treatment (OOAT) clinics in the state. Another 32 detox centres or drug de-addiction centres and 25 rehabilitation centres are now running in Punjab.

“Initially, the patients were charged a nominal fee for the treatment, but now, it is free at any government-run centre. Although personally I am against freebies, the government did it to encourage drug users to show up for treatment,” he said.

No denying there is a problem

Dr Bhola, who is also a technical expert and master trainer for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in South Asia, said there is no point in denying that Punjab has a problem.

“We are affected adversely by the drug problem, and it is not just the responsibility of the doctors or policemen to solve it. The community and civil society has to get involved. Sooner or later, it is going to knock at your door,” he said.

Although the exact extent of the problem is still not known, Bhola feels the situation is worsening. “National surveys show that the average age when a person starts trying drugs is going down to 10-11 years old. Studies conducted by AIIMS and PGI show that the number of women using drugs in Punjab is almost 1.5 per cent of the total drug users. But national surveys say women are almost 5 per cent of the total drug users,” he said.

Reading these trends, Bhola has now set up Punjab’s first exclusive drug de-addiction centre for women and children, in Kapurthala.

“It could be the first in India, and became functional last year. But we are still not getting too many patients,” he said.

“There is so much stigma to addiction that women — even those who want to be treated — will not come out in the open. But just last week, we’ve started a sensitisation programme encouraging women drug users to opt for treatment.”

Also read: Will making prescription opium available help solve Punjab’s drug menace or aggravate it?