Mumbai: Two months ago, Dyaneshwar Solanki, a farm labourer from Maharashtra’s Nagthana village, got a call from a relative, who claimed that his son had been perpetually sick because Dyaneshwar’s mother Sindhutai did black magic on him. He also threatened to kill off Dyaneshwar’s family.

According to Dyaneshwar, the relative had been visiting a self-styled godman in Nagthana, located in Washim district.

The farm labourer then went to the local police station to file a complaint, but claimed the police refused to register an FIR and filed a non-cognizable report (NCR) instead.

He then approached the Akhil Bhartiya Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti (ABANS), a non-profit established in 1982 by rationalist Professor Shyam Manav, which works towards dispelling superstitious beliefs.

“I contacted ABANS as what happened with us falls under the black magic law, but the police refused to register an FIR under it. I don’t know what to do,” Dyaneshwar Solanke told ThePrint.

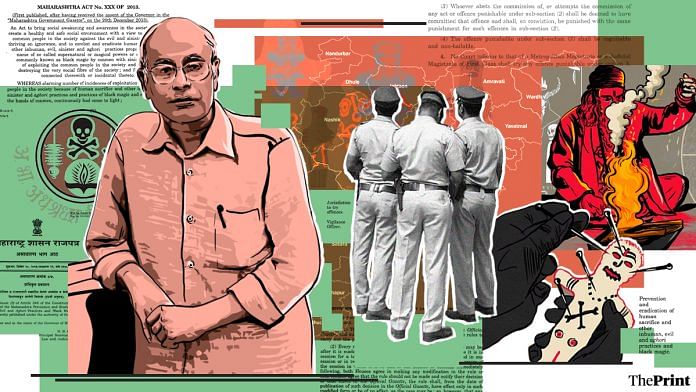

The Maharashtra Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifice and other Inhuman, Evil and Aghori Practices and Black Magic Act was passed in December 2013, after the daylight murder of anti-superstition crusader Dr Narendra Dabholkar on 20 August that year.

Offences under this law are non-bailable, and carry a punishment of six months to seven years and a fine of up to Rs 50,000.

Ten years have passed, but the law is yet to be properly implemented, said anti-superstition activists contacted by ThePrint.

From black dolls hanging from trees, to “goddesses entering a villager’s home”, these activists have seen a vast array of instances in Maharashtra over the past few years.

They attributed this to a lack of initiative by successive state governments, due to which the law had failed to make impact despite the multiple training sessions organised for police personnel soon after it was passed.

“The Act is in place but it should reach the masses. That is not happening, it is not being implemented,” Nandini Jadhav, a member of another anti-superstition organisation, the Andhashraddha Nirmulan Samiti (ANIS), which was founded by Dabholkar.

Soon after the law was passed, the Prithviraj Chavan-led Congress-Nationalist Congress party (NCP) state government had formed a committee for its planning and implementation.

The Jadu Tona Virodhi Kayda Prachar Prasar Samiti, which is still in existence, is headed by the social justice minister (in this case, Chief Minister Eknath Shinde, who holds the additional portfolio) and a minister of state. It meets twice a year, and members include secretaries of various government departments and representatives of NGOs.

“Implementation of the Act is very poor and the government’s intent to implement it is also doubtful,” said ABANS founder Dr Shyam Manav, co-chairman of the committee. “Cases are not getting registered as the police themselves are not aware of this Act.”

Activists also said that, till date, very few cases have been registered under the anti-black magic law, and even in those that were registered, the conviction rate is dismal.

According to Nandini Jadhav of ANIS, quoted earlier, only around a thousand cases have been lodged under the law since it was passed. “Conviction (rate) is very low because police themselves don’t know how to frame the case. We fight because we know the Act but what about common citizens who don’t understand it fully and are not able to explain it to the police?” she asked.

An official working with the social justice department on implementation of the law told ThePrint that since the anti-superstition law was passed, only around 250 cases have been registered under it till 2022, while over a thousand complaints had been received.

ThePrint reached Sumant Bhange, secretary, social justice department, for comment. This report will be updated if and when a response is received.

A government official in the know told ThePrint: “As it is for any government process, this one also takes some time. The governments changed in between so it is taking time. But we are proactively coordinating and implementing this Act.”

Also Read: Dhirendra Shastri, miracle-maker of MP, is only getting bigger after rationalist challenge

How the law came into being & what it says

From the time the initial bill was drafted by Dr Dabholkar, it took over a decade for the anti-superstition law to finally be passed. It was introduced for the first time in the Maharashtra assembly in 2005. Maharashtra was reportedly the first state to propose a law of this kind.

There were a lot of protests for and against the bill. Some groups branded it as “anti-Hindu” and one that curbs religious freedom. In July 2008, activists in support of the bill protested the then Vilasrao Deshmukh-led government’s apparent unwillingness to ratify it, by slapping themselves.

Things changed in 2013, after Dabholkar was killed. A day after the murder, under then CM Prithivraj Chavan, the state government decided to promulgate an anti-black magic ordinance. The law finally came into being in December.

Offences under this law range from human sacrifice, to assaulting or tying up a person on the pretext of expelling a ghost, display of “so-called miracles and thereby earning money”, to “creating panic in the mind of the public by way of invoking a ghost”.

Initial efforts to implement the law

According to Shyam Manav, soon after the law came into being, the state government provided the environment for training police and spreading awareness.

“In the first year, we did around 40 training sessions across all districts of Maharashtra. We trained key police officers on how to identify such cases and explained the Act to them. These were day-long sessions but went on for up to 7 hours,” said the ABANS founder.

“Sensitising the police force towards the Act was a big task. We had to use practical methods to explain what could fall under black magic or superstition,” he further said, adding that it was a task to get all police personnel to attend the sessions but the then government supported the endeavour.

“The training even started showing good results,” said Manav.

Parag Pote, a senior inspector, told ThePrint about an incident that took place when he was posted at the Sevagram police station in Wardha district in 2015.

“A rumour spread in the village that goddesses had walked into a man’s house. Many people started queuing up outside his house to do darshan of the goddesses. They started treating his house like a temple and 200-300 people would gather outside. Some even started giving donations like money, rice, coconuts.”

While investigating, Pote found out that the man who lived in that house had drawn footprints leading into his house to fool villagers. “I registered that case under the black magic law. I have so far registered four cases under it,” the inspector said.

Changing govts, pandemic delayed efforts

In 2014, a project to implement this Act through training programmes was initiated, but change of governments frequently derailed efforts.

Moreover, funds allotted for awareness rallies and training programmes started drying up and more funds were allegedly not sanctioned.

“I was told that funds will get sanctioned but for the next three years from 2015, it just went back and forth,” Manav said.

In 2019, the government changed and the Maha Vikas Aghadi (Shiv Sena, Congress, NCP) came to power. Once again it was decided that the project would take shape. Funds worth Rs 12 crore were sanctioned under the state budget in February 2020, and workshops for police, teachers, gram panchayats, schools, colleges, and other stakeholders were to begin from April 2020.

But the Covid-19 pandemic, especially social distancing once again halted these efforts. In 2022, the government changed once again.

Apart from training, the work included awareness programmes in 36 districts, 350 talukas, and villages across the state.

Activists said the state government needs to put up posters at public places like bus stops, or on buses or police stations for awareness about the anti-superstition law. This law needs to reach the masses via the government, they say.

ANIS also organised a lot of training camps initially. As soon as the law was passed, Jadhav said, they took out a ‘Jan Sanwad Yatra’ for 85 days to sensitise the masses. They did another such campaign for 90 days starting last August.

“What we understood is that the rules are not in place even 10 years later. And the police themselves are not aware of the law,” said Manav.

According to the ABANS founder, in the last one year, Manav said only three sessions had been conducted. “The government cabinet is not fully functional and the (social justice) department has its hands full. The political intent is lacking because committee meetings have also reduced,” he added.

Need of the hour

The need of the hour, activists said, is sensitisation of people, especially the police force. Even police transfers are affecting the process, they said, as those who have been trained get shifted out. According to the Act, the vigilance officer deputed by the government is the one who implements this law.

Pankaj Wanjare, an activist who works on ground for ABANS shared an incident, speaking to ThePrint.

“In 2015, a man living in Wardha district lost his newborn. The incident left his wife devastated. His wife’s family then started taking her to different ‘babas’ thinking she was haunted,” said Wanjare.

As a result, the wife started taking part in black magic rituals, which continued for eight years.

Finally, he approached Wanjare, who decided to approach the police.

“The police refused to take the complaint. They said that the police station, under whose jurisdiction the incident happened, did not exist back in 2015. So they are refusing to take action,” said Wanjare. “According to the Act, a complaint can be registered in any police station. That did not happen in this case. So we decided to help the woman instead.”

Pote said very few police officers are aware of this law. “And even in court, there is no provision to treat this like a special case or expedite the matter, so my cases are still in court.”

According to activists, some police personnel themselves believe in superstitions, making it hard for them to implement the law. “There is a lot of confusion about the definitions of superstition among the police force and hence victims are sent away,” said Manav.

In a village in Satara district, Jadhav encounters a bizarre ritual of black dolls hanging from trees every year. “Every year we take these black dolls off and burn them. And despite the local police stations putting out flyers about the black magic law, they have not registered a case. What is the system doing?” she asked.

(Edited by Gitanjali Das)