New Delhi: Another successful home season for India’s Test cricket team is complete with the home side retaining the Border-Gavaskar Trophy for a fourth consecutive time after beating Australia by a 2-1 margin. In the process, India sealed their spot for the World Test Championship final beginning 7 June against the same opposition.

Alongside this success, however, came the age-old debates over the nature of spin-friendly pitches that turn square and are prepared by local curators, reportedly at the direction of captain Rohit Sharma and head coach Rahul Dravid.

Meanwhile, those touring India had the opportunity to label such supporters as hypocrites with the Test result shoe firmly on the other foot.

Philosophical arguments about fairness, off-field intimidation and sporting behaviour run amok on a regular basis surrounding pitch preparation, with the International Cricket Council’s muddled pitch performance ratings system seemingly not helping matters.

However, seldom does such discourse, particularly in the mainstream, involve any serious engagement with the performances of these pitches and how they impact team performances over an extended period of time, across multiple tours.

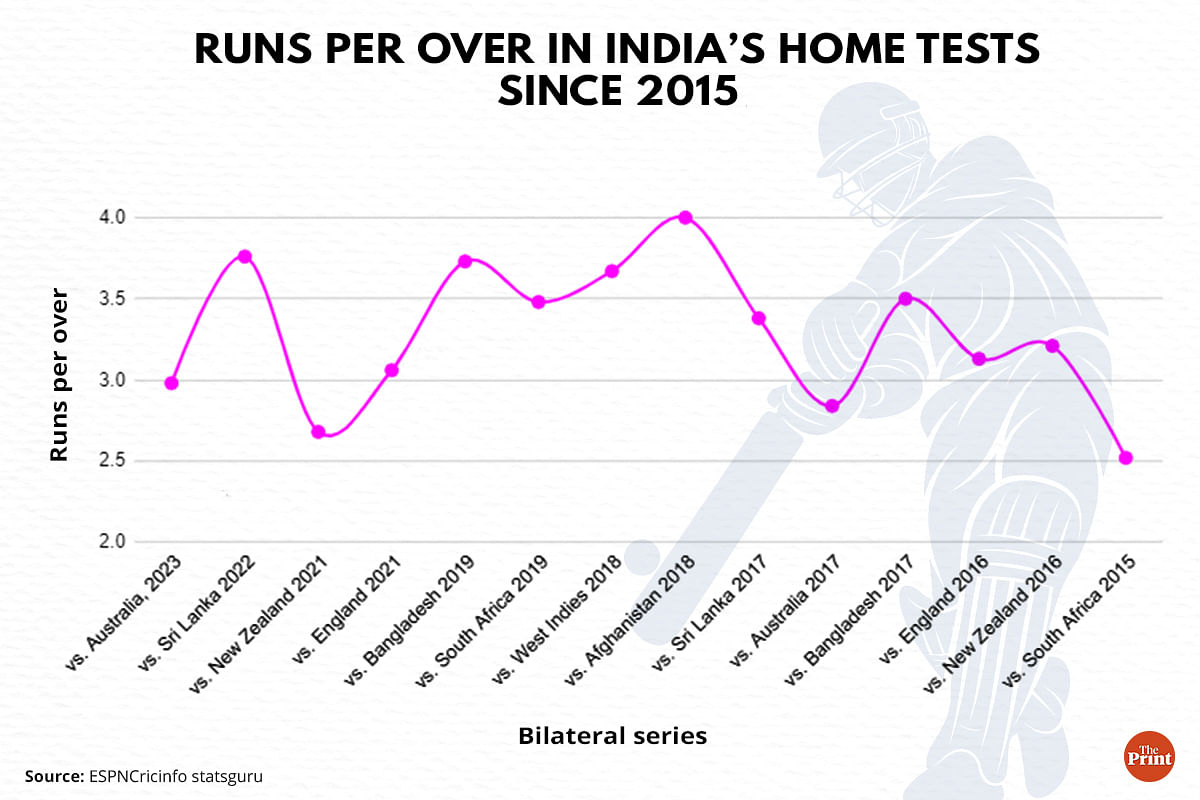

For the purpose of this particular analysis, we are limiting ourselves with India’s 2015 home season onwards, i.e. the captaincy tenures of Virat Kohli and Rohit Sharma, when India rose from a middling side in transition under M.S. Dhoni to a consistently top-ranked side.

This is not only to narrow our focus on the years leading up to the formation of the World Test Championship which incentivised more result-friendly pitches, but also to cover the post-2018 era of Test cricket which Australian analyst Jarrod Kimber terms as the “pace pandemic”.

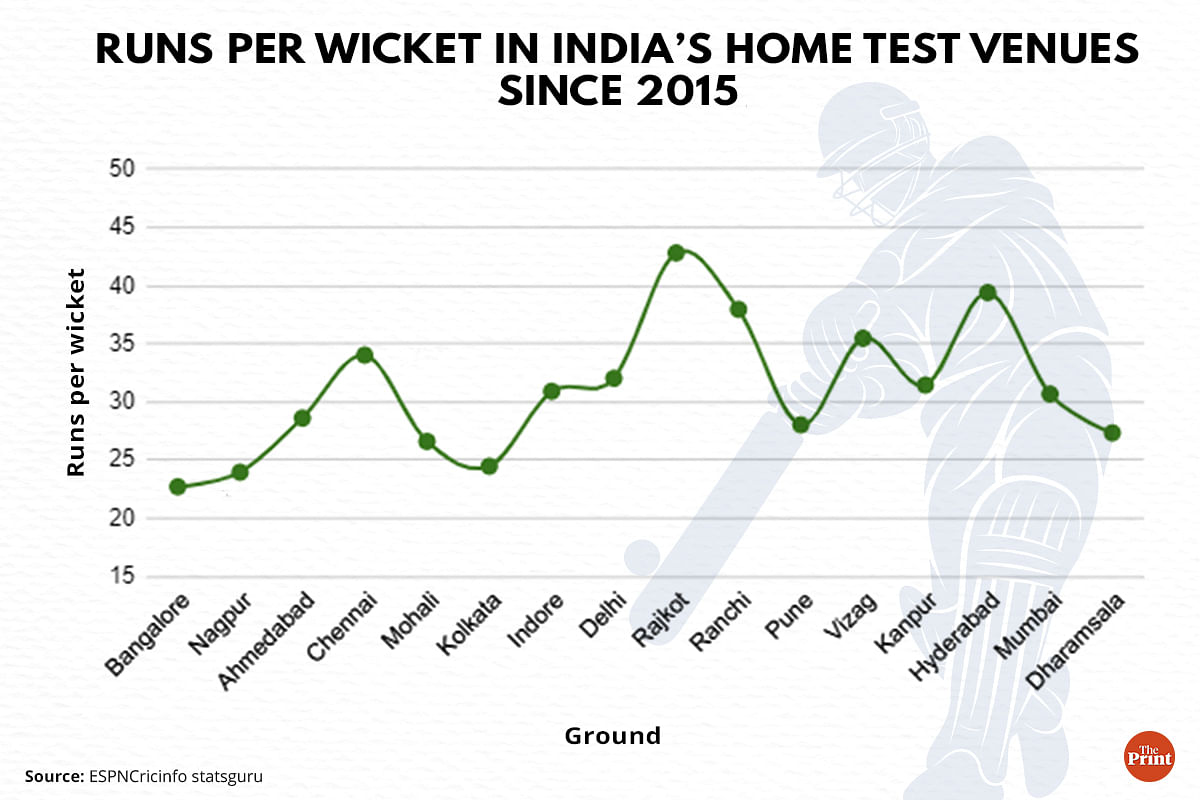

As such, aggregates of Test match scores featuring India and the touring sides have thrown up some predictable results but also a few surprises, while keeping in mind the small sample sizes that result from the BCCI’s Test venue rotation policy.

The most prominent contrast shown by Chart 1 is the average runs per wicket at Bengaluru versus that of Rajkot, with the former having hosted 4 Tests in the timeframe and the latter 2 matches before being usurped by Ahmedabad’s rebuilt Narendra Modi Stadium.

Interestingly, across these 4 Tests held in 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2022 that feature three India wins and one rain-affected draw, Bengaluru’s runs per wicket figure of 22.71 isn’t especially skewed by the rout of Afghanistan by an innings and 262 runs in its Test debut in 2018.

Rather, M. Chinnaswamy Stadium has largely been prepared to suit spinners across its 4 Tests regardless of opposition. Australian pacer Josh Hazlewood and Indian speedster Jasprit Bumrah have also enjoyed healthy returns. Bumrah took 8 wickets in a pink-ball Test under lights against Sri Lanka in 2022.

Rajkot, on the other hand, saw a pair of run fests, with the hosts in 2016 narrowly avoiding defeat to England. In 2018, India plundered 649 runs batting first against West Indies, before the spin trio of R. Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja and Kuldeep Yadav ran through the opposition batting line-up twice to inflict heaviest defeat on the visiting side.

Also Read: ‘Stats speak otherwise,’ Venkatesh Prasad’s takedown continues as K.L. Rahul falters again

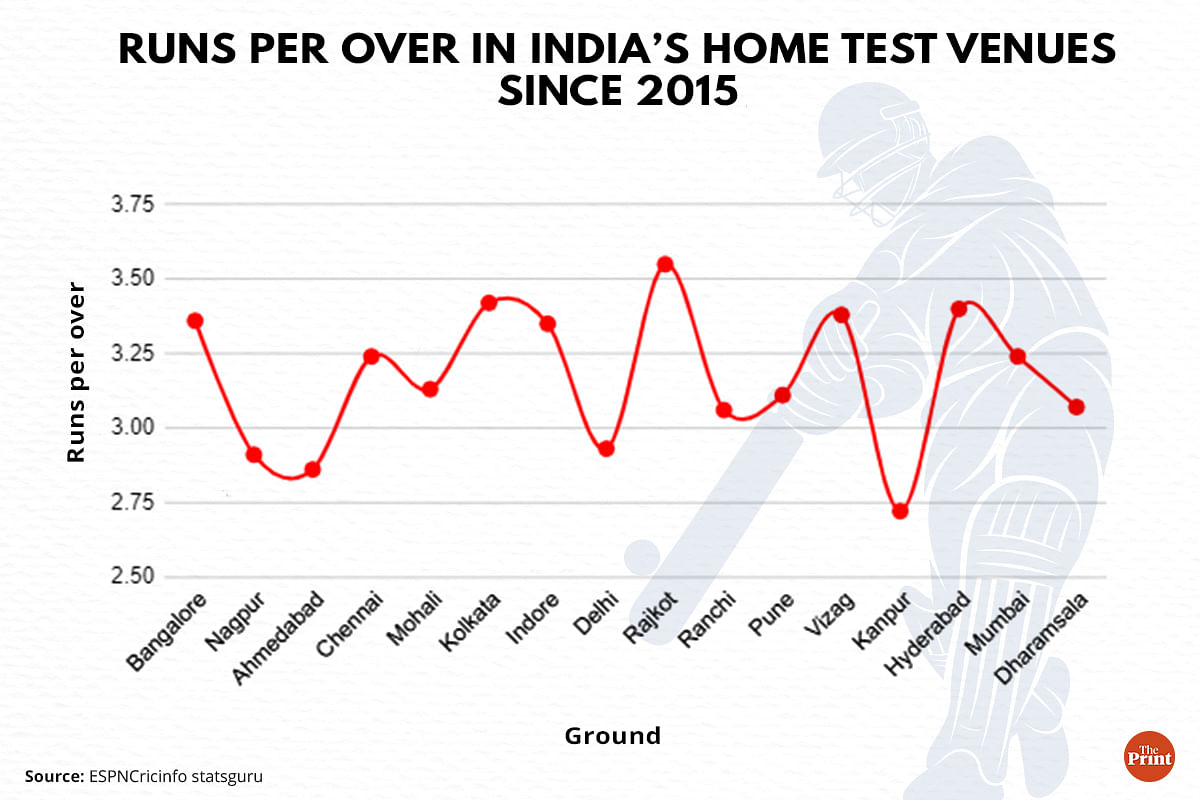

Chart 2 adds another interesting layer for these two grounds, which rank as the two highest average runs per over across our timespan at 3.36 and 3.55 respectively, for apparently different reasons.

Rajkot has simply been a flat pitch, allowing top order batsmen from India, England and even West Indies (like in Kieran Powell’s case) to cash in early without worrying about excessive variable bounce or lateral movement that would only show up in subsequent days.

Bengaluru, meanwhile, fits the stereotypes associated with Indian pitches where top sides like India and Australia are able to trust defensive techniques and grind it out while facing each other.

Less talented sides at the time like Afghanistan, Sri Lanka prior to Chris Silverwood’s appointment or South Africa following exits of Jacques Kallis and Graeme Smith appear less confident in their defences and try to score quickly before that unplayable ball is delivered.

As a result, the devil in Charts 1 and 2 lies in the details of the other venues. Nagpur and Mohali, for instance, were much-maligned in 2015 for being so spin-friendly that the teams struggled to score over 200 runs and part-timers like South African Dean Elgar were able to cash in.

Over the years, the pitches have largely played more evenly allowing not only India to score big in favourable conditions but also accentuating the skill gap between the home and away sides. The venues’ respective averages and economy rates are a result of this evolution, and India have enjoyed 100 per cent win records at both venues in this span.

From the broadcasters’ point of view, the most sporting venues from this list are perhaps Mumbai, Kanpur and Chennai, with the pitches playing true enough to last all five days and either ending in a positive result, or even a thrilling last-gasp draw as seen in the recent Kanpur Test.

Delhi’s first two Tests from this span in 2015 and 2017 also fell in this category, but the pitch prepared for the recent Border-Gavaskar series was the exact opposite. Other marquee venues like Ahmedabad show outlier cases like the truncated day-night Test in 2021 where the pronounced seam of the SG-manufactured pink ball was believed to led to the batting collapses and created the ideal conditions for English cricketer Joe Root’s five-wicket haul.

The biggest contrast within the confines of a venue’s sample size lies in Pune, which was the site of a resounding Steve O’Keefe-led Australian win on a turning pitch in 2017. Two years later, a flatter track saw India steamroll South Africa, with Mayank Agarwal and Virat Kohli scoring centuries before Umesh Yadav combined with the spin attack to secure an innings victory.

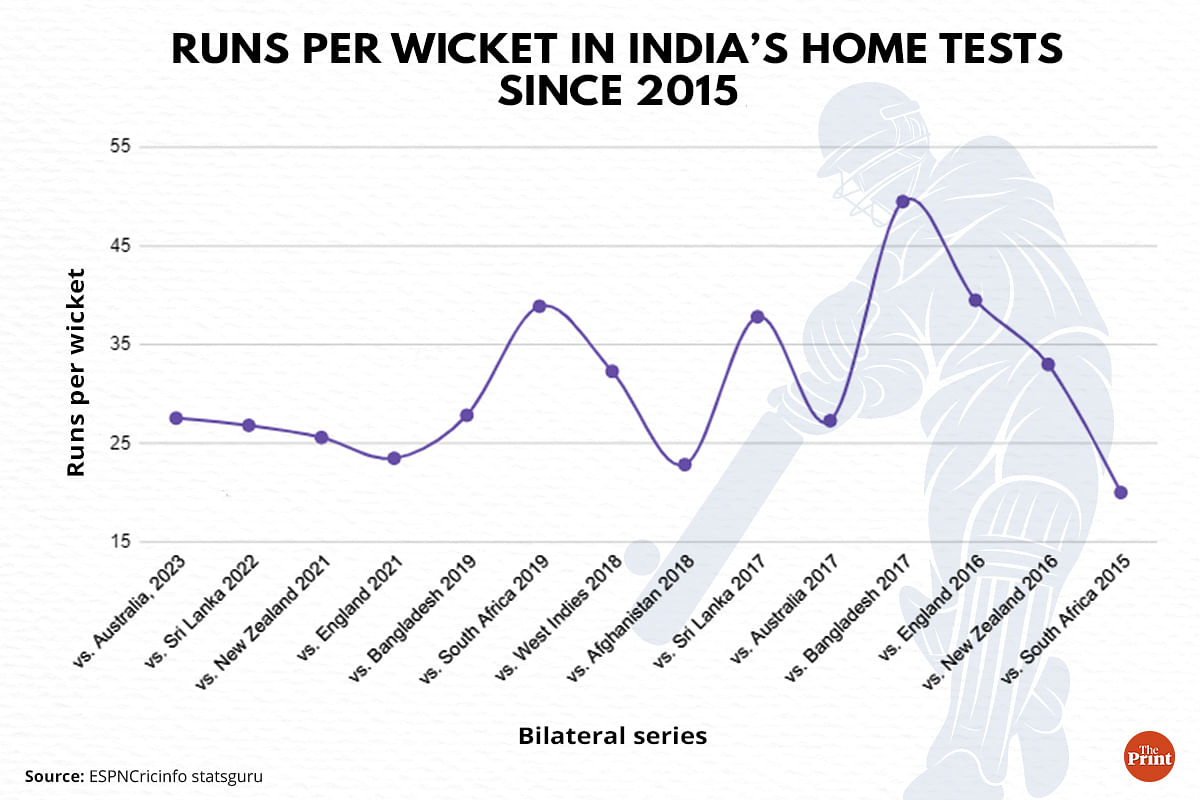

The analysis of venues show the extremes with which the nature of pitch preparation has oscillated over the past eight years. But even more significant than that is the apparently deliberate tactic of preparing pitches depending on the opposition touring India.

It is a well-known fact that India’s lower order batsmen and spin attack has, of late, often bailed out a top order that struggled to score consistently, especially in the 2021-23 cycle of the World Test Championship.

Charts 3 and 4 evidently show a concerning trend to that end, with significantly lower runs per wicket and runs per over since 2021 on largely bowler-friendly wickets where run scoring is more common when the red ball goes softer.

They further lay bare the contrast between prior series where more batting-friendly pitches were prepared from 2016 to 2019, save the 2017 Border-Gavaskar series when curators reverted to the so-called dust bowls.

Partly responsible for this trend is the World Test Championship cycle, which discourages preparation of pitches that don’t offer as much to seamers or spinners and risk leading to the kind of drab draws we saw in Ahmedabad last week.

However, as noted by Kimber, India were not only relatively late to the “pace pandemic”, given their batsmen’s healthy returns at higher scoring rates from 2018 to 2019, but most of senior top order batsmen have also experienced prolonged periods of low scores due to conditions favouring bowlers both home and away.

“India has historically been a great place to bat, meaning their batters all have fantastic averages compared to other countries. Now it is not, and with the rest of the world struggling to bat as well. It means there is nowhere to hide for an Indian batter…Conditions are about as tough for Indian batters as they have ever been.

“It should mean that we are factoring that into the new lower scores. How much more — or less — you score than an average top-order player is now a good metric to look at for Indian batters. But where is the fun in that when you can just suggest they should all be dropped?” Kimber argued in defence of the Indian batsmen.

India’s selection strategies have often faced questions over decisions such as handing a Test debut to Suryakumar Yadav instead of Sarfaraz Khan. The declining quality of opposition, particularly in 2018 and 2019, contextualises some of these numbers.

But the data since 2015 reflects the continued risks of playing with fire. Relying on lower order and spin depth may safeguard India’s fortunes at home and keep it in contention for the World Test Championship final, but set up the primary batsmen for failures abroad and lead to selection and tactical headaches.

Moreover, there will be an odd match where opposition spinners can induce batting collapses on pitches with sharp turn and inconsistent bounce, as done by Nathan Lyon, Todd Murphy and Matthew Kuhnemann in the recent weeks.

Among those involved in this cricket discourse is star spinner R. Ashwin, who referred to the Delhi pitch for the second India-Australia Test as “tricky” and the inconsistent bounce as unique to Indian cricketing conditions, particularly in the North, in the winters.

“During the morning, there will be some moisture on the surface and thus some pace off the pitch. That’s exactly what happened in this test match. During the first session, wickets fell but the pitch got slower later. If you settle on that wicket, you will stitch together a partnership,” Ashwin said on his YouTube channel on 25 February.

Coach Rahul Dravid and captain Rohit Sharma cannot influence the tactics and decision-making of oppositions and curators when India tours England and the West Indies. But perhaps what can be looked into is, for instance, more Kanpur-style pitches that remain result oriented and geared towards India’s historic strengths while still offering consistent bounce and turn designed to be played on for the full five days.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: As Odisha gears up for hockey World Cup, here’s how new rules have made the game much faster