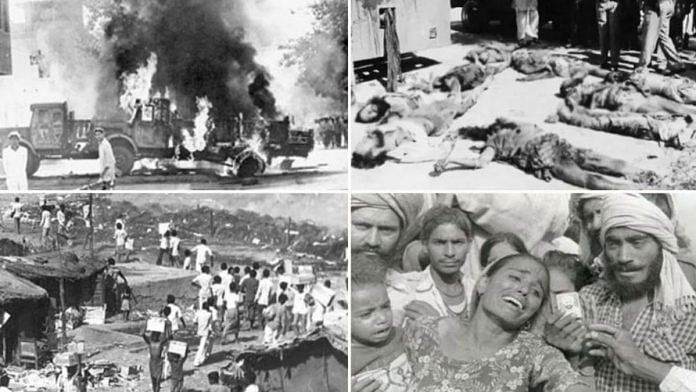

The carnage that swept so much of the national capital and parts of the country last fortnight was an unprecedented, uniform reaction to the slaying of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by two of her own guards.

For the first time, it was the Delhi region, protected and pampered, that bore the brunt of the anger and the orchestrated, myopic reprisals against the Sikhs.

If, fortunately, it was less murderous in the states, the worst was in the Hindi-speaking northern and central states of Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Haryana.

The pattern, most vivid and bloody in Delhi, was nausea-tingly repeated elsewhere: spontaneous arson and destruction at first taken over by criminally led hoodlums who killed Sikhs, looted or burnt their homes and properties while the police twiddled their thumbs.

In desperation and fear, Sikhs vanished from the streets and, in traumatic acts of self-preservation, shed their turbans, cut their hair and shaved their beards. The toll around the country remains uncounted and tens of thousands have been crammed into hastily put together refugee camps and a benumbed country is only just beginning to grasp the magnitude of the violence it has inflicted upon it self.

Reports have also poured in from all over of Hindus going to the help of Sikhs, of saving neighbours and friends, even strangers, from the fury of the lumpen elements that made up the killers and looters. While in northern India, the overwhelming reaction was of mobs turning on the innocent, in southern India there was a unique atonement.

In Madurai, 200 men, women and children shaved their heads. At least eight committed suicide in Madras. In Trivandrum, the mobs merely burnt effigies, while in Karnataka there was sporadic destruction of property without loss of life.

Mercifully, the one state where reactions could be expected, tense and troubled Punjab, seemed to be holding under the watchful eye of the army and the para-military forces.

And, as the country limped back to normal, it rapidly became clear that certain low-level political elements had been using the same reservoir of toughs for hire that have rounded up manpower to fill their rallies.

It radiated like a powerful wave from the perimeter of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) borne on the wind of rumour and swept by a growing anger even as doctors fought their losing battle to save the life of slain premier Mrs Indira Gandhi.

The steadily thickening crowds set up an unending chant of slogans, which wafted all the way up to the 8th floor operation theatre and the corridors where mourners gathered to take stock and discuss the next moves. The slogans were vicious, and the scuffles with the police getting uglier.

The final irony came when President Zail Singh’s cavalcade, making its way from the airport to the hospital, was stoned by frenzied crowds who were already besieging passing Sikhs, burning their vehicles.

The President’s outrider was obliged to remove his turban, and the President’s press officer, Trilochan Singh, barely saved his life, fending off lathi blows with a seat ripped out of his car.

Finally, the wave burst outwards with pent-up fury and swept the Union Territory in an uncontrollable deluge. Three days of violence and loot and murder left the national capital dazed, reeling from an unprecedented holocaust.

As a senior home ministry official, contemplating the murder of untold hundreds, later said: “What happened in those three days will remain my life’s most painful enigma. We always thought that such carnage could only take place in far-off Assam, cut-off areas like Mandai or Nellie. Here we had it all happening not 10 kilometres from Rashtrapati Bhavan.”

While a lot of it was rumour, there were isolated cases of an irrational Sikh celebrating the assassination. But an emotionally surcharged population was more inclined to believe rumours. The bubble had to burst.

It had been filling through nine months of extremist violence against Hindus in Punjab, a reign of terror that came to an end only when the army cleansed the Golden Temple and other shrines in Punjab.

But the resentment simmered, and the inevitable denouement came when two Sikh assassins, traitors not only to the nation but betrayers of their own faith, riddled the frail body of the 67-year-old prime minister with lethal bullets.

Also read: ‘No differential treatment’ — SC rejects bail for 1984 riots convict suffering from Covid

The first day, the violence was localised. News was indistinct, there was a profound sense of shock in the air. But the next day, 1 November, a different story was being written. Violence spread swiftly, to other parts of New Delhi, to respectable neighbourhoods, areas of expensive tenements, exclusive shopping areas.

It swept Connaught Place, Vasant Vihar, Maharani Bagh, New Friends Colony and Hauz Khas, where rents run in several thousand rupees a month and peace normally reigns. Pachkuian Road’s furniture shops were made bonfires of, and in Chandni Chowk, saris worth an estimated Rs 15 crore were dumped in the famous Paranthewali Gali and set ablaze.

Delhi’s fire department worked overtime in a futile bid to keep the fires under control. Said S.P. Agrawal, the municipality’s deputy director in charge of water: “It was absolutely unprecedented. As against an average of 10 minor and major fire incidents a day, we were receiving well over 100.”

Even so, in terms of what was yet to come, it was restrained. From the rooftops of Connaught Place, columns of black smoke rose high into the sky, the smell of burning assaulted the nostrils. There was arson everywhere, shops and homes set on fire, taxis and lorries destroyed, property looted.

There was an emotional undercurrent to it, but no one failed to notice the absence of the middle classes from the perpetrators of this violence in the very middle class areas that it occurred. The signs already were ominous that this was the handiwork of marauders from outside, not a spontaneous outpouring of grief.

In retrospect, it was as if the water was being tested. Looting and burning, the marauders were stopped by no one, certainly not the demoralised, ill-equipped, depleted and poorly led ranks of the Delhi Police whose substantial Sikh cadre had immediately vanished from the scene.

The lapses were to prove fatal. For the violence acquired a new, bloody pattern the very next day, on November 2, even as Mrs Gandhi’s lifeless body lay in state at Teen Murti House.

On that day, the mobs began to kill, with deliberation, with cold-blooded calculation, picking on helpless men, women and children, burning them alive, roasting them in their homes, cutting them down wherever they could be found.

In some places, the Sikhs responded with counter violence, inviting harsher retribution, but the casualties spanned both communities. Several hospitals reported that casualties coming to them were a mixture of Sikhs and Hindus. But the Sikhs were outnumbered, and soon it became an unequal battle.

Block 32 in Trilokpuri in the trans-Yamuna region of the capital wasn’t typical, but it became a deadly testament to the agony of that black weekend. For days after, the streets of Trilokpuri were heaped with smouldering corpses. Said a dazed Jasmer Singh, a jhuggi-dweller who survived: “They would incapacitate a man, douse him with kerosene and touch him with a burning torch.”

Other survivors are still incredulous at the suddenness and devastation of the assaults. “What happened, what went wrong?” wailed Kartar Singh sitting outside his burnt-out house.

“We had always voted for her.” On one wall, a half-burnt calendar picture of Mrs Gandhi survives. “They killed her a hundred times over,” he moaned repeatedly.

The tell-tale signs of madness lay all over the burnt-out hulks of the ghettos. In one hut, a bunch of shattered picture frames show martyr Bhagat Singh in the company of numerous Hindu gods and goddesses and Sikh gurus.

In the adjoining one, the charred calendars are all of Hindu deities — it belonged to a family that tried to help its neighbours. People like that were the special target of mobs.

Hans Raj, a building contractor had a horrendous experience. On the evening of 1 November, he was a contented man, having completed the shopping for his daughter’s wedding scheduled for next month.

“I had put my life’s savings into it, but I was satisfied,” he now says with a faraway look. When the madness struck, he took in some Sikhs to protect them from the marauders.

“That was the excuse they needed,” he says raising his heavily bandaged arms to his forehead. “See how they beat me up, burnt my house, took away everything, all of my daughter’s dowry.”

Kuldip Kaur, who lost her husband and three children, describes how a Hindu neighbour saved her by hiding her in a large steel trunk and putting a heavy padlock on it. “For two days I lay crouched in it” she says, “I even defecated inside. But I am alive.”

Others weren’t as lucky. The death toll in Trilokpuri is estimated to be nearly 500, a major part of the unprecedented carnage that has accounted for more than 1,000 people in the capital.

The exemplary camaraderie between Hindus and Sikhs was the only redeeming feature in an otherwise sordid story. The signs Were everywhere, in outlying colonies like Mongolpuri, Kodapur, Inderpuri, Tughlakabad, Palam.

Among the affluent colonies, the worst affected were those bordering on villages or resettlement colonies. Others to bear the brunt were new colonies of mixed communities where bonds had yet to be established.

In the more central parts of Delhi where violence first began on October 31, instincts were not quite as murderous. Also, the mobs there had no chance of trapping large bodies of Sikhs in confined areas. They concentrated on arson, assault, and most important of all, looting.

On the first night itself some of South Extension’s better-known showrooms — Perfection Silk and Sari House and Wings Shoes had been burnt down. Immediately, the mob’s attention was turned to taxis driven by Sikhs. Soon, the Ring Road and the roads leading to Palam and Safdarjang airports were lit with blazing cars.

The mayhem moved to downtown Delhi the following morning. Along the radial roads emanating from Connaught Circus, veritable infernos blazed in the furniture market on Pachkuian Road, the congested lanes of Paharganj and the timber market near Shiela Cinema.

An India Today correspondent saw a glass and mirrors shop where a Sikh had died when large sheets of glass fell upon him, slicing his body. Barely two kilometres away, the Bangla Sahib gurdwara bore a forlorn look, with its car park covered with brickbats. The gurdwara itself was safe thanks to stout defence offered by youngsters armed with iron rods, kirpans and the odd firearm.

In Connaught Place, the first cars were burnt on Janpath Lane. Close by, in front of the Imperial Hotel, a group of Sikhs stood defiantly to prevent attacks on their taxi stands.

With huge columns of smoke billowing all around, Connaught Place looked like a battlefield. Among the buildings that were burnt were Uberoi Opticians, Marina Hotel and some shops owned by Sikhs in the Regal building.

Also read: Don’t question Sikhs helping Muslims. We know what hate is and does

The residential colonies too soon fell victim to the mob fury. In New Friends Colony east of the Mathura Road, houses of two former chairmen of the Punjab and Sind Bank, Mohinder Singh and Bhai Inderjit Singh were burnt. In nearby Maharani Bagh too, mobs came in with clear-cut lists bearing the numbers of houses owned by the Sikhs.

The trend was repeated in the south Delhi colonies of Safdarjung Enclave, Vasant Vihar and Hauz Khas. In the southernmost colony of Saket, mobs came in a row of three-wheelers with almost martial elan and burnt down the beautiful new gurudwara, leaving the granthi for dead. He was later rescued.

On Mathura Road past Nizamuddin, at a sand and gravel depot as many as 50 lorries owned by Sikhs had been set on fire. The adjoining Bhogal area was even worse hit. Said Sardar Ranjit Singh, president of the badly damaged Bhogal Singh Sabha Gurudwara: “Thousands have come since the morning shouting slogans of Indira Gandhi Zindabad and set fire to our trucks and buses. At least 80 vehicles have been burnt.”

Close by, on the Ring Road, the Bawa Holiday Inn, a large double-storeyed bungalow converted into a guest-house, was on fire. But by far the most pathetic sight was the Guru Harkrishan Public School in Vasant Vihar. The school was gutted, the furniture, books and equipment all burnt and even the ceiling fans dropped down under the heat of the fire.

The school, popular with children from all communities, has now been closed indefinitely and it seems it will be some time before the senseless damage will be repaired. Everywhere the police were mute spectators. In retrospect, a strong factor behind the violence was the proximity of each exclusive colony to a resettlement area or village.

Over the years, that has been the pattern of development in Delhi. On this occasion, the reaction against the Sikhs was to provide justification for the letting out of all the pent-up envy arid anger of the poorer neighbours. Similar motivations seemed to be at work as small-time farmers formed the bulk of mobs that attacked the sprawling farm houses on the Delhi-Gurgaon Road.

Among those burnt was one belonging to author Patwant Singh. Outside town limits, the Olympus microscope factory owned by the Dhingra family, was burnt along with the Dhingra house. Heavy damage was caused to Congress(I) MP Charanjit Singh’s soft-drinks plant.

The irrationality of it all was evident in the way the violence engulfed people of both communities. Said S.P. Malhotra, a Malaviya Nagar businessman and one of the leaders of the citizens’ vigilantes in his locality: “There is no way a mob can hire only people from one community. The flames can’t tell a Hindu house from one owned by Sikhs.”

At Kishengarh village near Mehrauli, a seven acre industrial estate was completely destroyed in a fire as the mobs attacked factories owned by a Sikh. What they did not realise was that four of the six factories in the estate were owned by the Hindus. Yet, within the estate, Hindus came to the Sikhs’ aid with no feeling other than camaraderie.

Says Harjeet Singh Bawa whose Bawa Potteries factory was completely destroyed: “It was not a communal riot but just an orgy of looting because of the breakdown of law and order. They even took away our flower pots. The Hindus have saved us or we would have never survived.”

Among the many tragic ironies of the mindless phenomenon was the burning, in Najafgarh, of a Hindu-owned furniture factory just because its manager happened to be Sikh.

The feeling of insecurity was acute enough to drive the most prominent Sikhs into hiding. Journalist Khushwant Singh took the name-plate off his Sujan Singh Park flat and moved over to the safety of the Swedish Embassy. Industrialist Raunaq Singh moved over to the safety of one of the more exclusive hotels.

Many other prominent Sikhs replaced the name-plates outside their houses with those bearing common Hindu names. The Imperial Hotel on Janpath was the prosperous Sikhs’ favourite hiding place. It was quickly converted into a stockade guarded by employees and friends of its Sikh owners and residents. In most of the attacks the motive was mainly looting.

In fact, later in the fortnight as army and police patrols raided the villages and resettlement colonies and asked people to voluntarily leave the looted property on the street-corners or face searches and legal action, goods worth over a crore of rupees were recovered in a day proving that the mobs that ransacked Delhi last fortnight consisted of mere ruffians and lumpen elements and not communally charged zealots out to take revenge.

Whenever the police decided to act, mobs just melted away. In fact, they never even faced up to the vigilante squads hurriedly put together by the citizens against them.

In fact, the vigilantes, who proved more effective than the police, were a veritable collection of middle class rabble armed with anything they could come across. There were old men wielding their walking sticks like lathis, youngsters carrying hockey sticks which were by far the most effective weapon, and iron rods.

Often patrols looked like an excited bunch of roadside cricket players with men carrying bats and wickets in the vanguard. Officers in both the police and the army acknowledge the fact that it would have been impossible to contain the riots so quickly.

If initially the marauding gangs had a field day, it was because the police all but evaporated precisely the moment that they were most needed. Of the capital’s 30,000-strong police force, some 6,000 were on leave.

A good proportion of the remainder were on VIP duty, protecting the dignitaries, domestic and foreign, beginning to descend on the capital., And those that were in the streets displayed a remarkable reluctance to perform their duty even in the face of direct provocation’.

At Paharganj, as irate mobs pillaged, a middle rank police officer stood by with a posse of constables watching quietly. When an India Today correspondent remonstrated with him, he feigned helplessness: “With our resources, what can we do? We are all waiting for reinforcements.”

Even as he said this, his men were watching in amusement as two Sikhs wielded traditional swords to keep a large mob at bay. Barring parts of Central Delhi, the police turned their backs on the Sikhs. Said Gurminder Singh, a trucker from Bhogal: “It all happened in the presence of the police.”

Also read: It isn’t first time Delhi Police probe into riots is being questioned. Happened in 1984 too

The most telling cases of police apathy were reported in east Delhi. The suspension and arrest of S.V. Singh, the station house officer (SHO) of Kalyanpuri police station which is responsible for Trilokpuri, was a tardy admission of this. But the entire system seemed to have collapsed.

The first officer to reach Trilokpuri got there 30 hours after the carnage started, even though the Indian Express reporters who had first reached there had rushed to tell the police of what they had seen a good 12 hours earlier.

In a complaint to the police commissioner Indian Express reporters Rahul Bedi and Joseph Malliakan accused Police Additional Commissioners Nikhil Kumar and H.C. Jatav and Deputy Commissioner Seva Dass of negligence. Kumar’s defence was that he, being under orders of transfer, was merely a guest artist in the control room.

Worse than negligence were the clear cases of complicity. Eyewitness accounts abound of police giving rioters the nod, turning a blind eye to murder and loot under their noses. At AIIMS, policemen were not just mute spectators, they were active participants.

At Trilokpuri, resident Rajpal Kaur is prepared to swear on oath that a police lorry drove past her many times during the orgy of killing. “Every time it went past, I looked out of my hiding place hoping it would do something, but the police would do nothing,” she later said.

The police could justifiably say it was in a state of shock after two of its ranks had shot the prime minister dead But, as a senior Home Ministry official pointed out, it was at precisely this moment that high quality leadership was needed. Instead of providing this, the top ranks did the opposite: they withdrew the entire Sikh constabulary, some 20 per cent or 6,000 men, further depleting the ranks of the police.

As always, there was a grain of truth about the excuse given: that the sight of a Sikh policeman would be as a red rag to a bull. But a skillful command would have been able to handle this differently, using the Sikhs in the police in ways that wouldn’t bring them in direct conflict with the public.

As it turned out, a Sikh ‘versus non-Sikh controversy has simmered for years in the ranks of the police, and this action could only have demoralised the Sikh officers who suddenly found themselves some kind of out-castes. This was a crucial failure: in the city’s policing system, the SHO is a key operative, and 13 of the capital’s 66 SHO’S and four of its 21 additional commissioners are Sikhs.

In retrospect, there is general agreement that the army should have been called out the first day, if only as a precautionary measure. The army was called out in the early afternoon of November 1, but was nowhere in sight that day. Isolated lorries began to be seen that night ,and the next day the army presence was more evident.

But nothing short of a judicial inquiry can show why the army clampdown was not fully to effect till after the cremation on November 3. But it is known that while Rajiv Gandhi was keen to call in the army on the first evening itself he was advised by Home Minister Naraslmha Rao to wait a while.

Gross though their failure was, the culpability of the police in the tragedy would rank next only to that of the Congress(I) politicians in Delhi.

Also read: Kejriwal is wrong. Delhi to Gujarat, outsiders blamed in riots, but most victims know attackers

At over two dozen scenes of violence that India Today correspondents visited in the course of their investigations, the local people, including Hindus, pointed the finger at the local Congress(I) leaders. The Sikhs were too scared to name anyone. But there were other strong pointers.

The shameful scene created at the Karol Bagh police station by Congress(I) MP Dharam Dass Shastri who protested against the police raids on villages in his constituency to recover looted property Shastri said he did not mind the police recovering stolen property but insisted that the people should not be arrested as they were “not criminals”.

Shastri nevertheless dismisses this as a campaign by his rivals, in his party. Brahm Yadav, the Delhi Youth Congress(I) president, went a step farther, trying to counter joint army and police raids in Kodapur, a part of his bloc.

After widespread killing and looting by mobs, an army officer, assisted by the local SHO, raided Koda and arrested a group of armed Hindus. Yadav promptly complained to the lieutenant-governor that the’ “Sikh” army officer accompanied by a “Sikh” SHO had no business to, be in his area and that they were acting in a communal manner. Subsequent inquiries show that the officer was only trying to do what was expected of him in the area allotted to his unit.

The congress(I) politicians suddenly came into the limelight just as the army and police began recovering looted property and arresting hoodlums. At prartically each police station in the capital, small-time Congress(I) politicians could be seen pleading with police officers to let their men go. “Where were they when the same men were burning their city”, a police officer asked angrily.

Ironically, perhaps the only aspect of peacekeeping on which the army and the police officers agree in this surcharged situation is in their threat perception. And the finger invariably points to the Congress(I). “Have you ever wondered,” asked a cynical army officer, “why is it that all the requests for the release of people are coming in from the Congress(I) leaders and not those of the other political parties? Do you need better evidence?”.

Starker evidence was, however, available to a party of newsmen visiting the riot-torn east Delhi colonies. On failing to dissuade them from touring the area, a police patrol quite openly set a bunch of rioting hoodlums upon them. The scribes barely escaped injury but were deprived of their pens, notebooks and other belongings.

But as they trooped into the police station to make a complaint they found highly apologetic local Congress(I) leaders requesting them not to make an issue of it and promising to return all their looted belongings. The politicians’ confidence that the hoodlums would return the things at their bidding only betrayed some of the criminal connivance that took such a bloody toll last fortnight.

Similar reports were brought in by practically all the volunteers working with the relief agencies. It was on the basis of these that the Opposition wrote out an indignant memorandum to Rajiv Gandhi who, while denying Congress(I) interference, seemed genuinely concerned and promised to caution overzealous partymen.

Besides complicity, the Congressmen were also guilty of their total absence from the peacekeeping effort. For days after the clashes no serious attempt had been made by a Congress(I) man to organise a peace march or committee.

Now, with the initial frenzy over, policemen say there is no chance of their handing out deterrent punishment to the hoodlums unless political pressure eases completely. Besides arrests wherever specific information is available, the best, long-term remedy in such situations is the imposition of collective fines.

Securitymen point out that if each theatre of violence is studied carefully it is easy to pinpoint the outlying villages or suburban colonies from where the marauding hordes came. This can be further confirmed by comparison with the trend of recovery of looted property. The guilty villages and colonies would thus be marked out and made to pay deterrent collective fines.

But police officers wonder if that would be possible considering the fact that the outlying colonies have always been getting favourable treatment from the Government. Most of the irregular constructions have been legalised, liberal loans given and the Congress(I) leaders have no hesitation in claiming that these areas mean something special to them.

“These are not just their vote banks, they are also their rally banks,” says a frustrated police officer pointing to the fact that in recent years these colonies have provided the bulk of manpower for the various Congress(I) rallies in the capital.

Officers point to the fact that unless strong action is taken now, the ruffians who brought this unprecedented disgrace to the capital will be tempted to repeat this orgy of looting and murder. And there is no scope for complacency, for the next flashpoint may not necessarily be all that distant. It could be the slightest hint of retaliation in Punjab, or even a mere rumour of it.

But it is also time those running the law and order machinery did a bit of introspection. The current peace is a tribute not so much to the belated police or army action as to a sudden realisation of a new balance of terror between the two communities.

Even those who did not exactly condemn violence against the Sikhs initially now fearfully talk in terms of retaliation in Punjab. In that hapless state, on the other hand, there is a new realisation of the vulnerability of Sikhs who have lived and prospered happily in all parts of the country.

But this balance is at best a precipitous one and leaves no room for complacency. For it would not need a resumption of violence in Punjab or elsewhere to upset it. A mere rumour of it could bring disaster.

Also read: Gujarat 2002 was independent India’s first full-blooded pogrom. Delhi 1984 was a semi-pogrom

High Priests — Contortions

Flip-flop-flip. That has obviously been the nature of the Akali response to the political challenge in their own state since the rise of the Bhindranwale factor.

Last fortnight even as Mrs Gandhi was assassinated and riots broke out, the surviving rump of the Akali leadership did no better than its past records – and caused formidable problems in the process.

First of all, on October 31, came the Akal Takht head priest Giani Kirpal Singh’s statement condemning the murder. The AIR and TV prominently broadcast it. But the following day major dailies of the capital carried on page one denail of having issued the statement.

Sources in Amritsar confirm that the priest had issued the retraction under pressure from hawks within the Akali Dal. All along, the surviving moderates like the then ad hoc committee chairman Prakash Singh Majitha and former MP Balwant Singh Ramoowalia were persuading him to take a conciliatory line.

Their efforts bore fruit on November 2 as the priests issued yet another statement condemning both the assassination and violence against the Sikhs. But he added, almost menacingly, that the Sikhs out side did not need to worry as the whole panth was with them.

This led to another statement on November 6, when the priest reportedly said: “Hindus have saved the Sikhs in Delhi. Now we must ensure that the Hindus are not harmed here.”

But this last was only a case of a section of the media getting it wrong. The priest were upset at the statement, apparently issued to the UNI in Delhi by Bakshi Jagdev Singh, the pro-government Sikh leader.

Almost out of the blue on November 8 the UNI came up with another story, that earlier on they had wrongly attributed the statement to the Akaol Takht head priest. It was in fact the text of the cable sent by Jagdev Singh to them.

Further dashing the hupes of a conciliatory stance was the report of the purge of moderate elements, openly called pro-Congress(I), from the Akali Dal ad hoc executive.

In a surprise move the committee headed by the soft-spoken Pakash Singh Majitha was disbanded and Surjan Singh Thekedar, a relative hothead, appointed the party’s convenor. This was obviously a victory for the hawks.

Had the high priest kept their feeling to themselves, had some prominent spokesmen publicly condemned the assassination, much of the trouble that followed could have been avoided.

Punjab & Haryana — Uneasy calm

For Punjab, the spectre of Operation Bluestar is back again. Uncertainty, tension, fear and anger stalk the harried state which has so far demonstrated an uneasy calm.

But the first unsettling noises came on the evening of November 5 as four Hindus were shot dead, two each near Jalandhar and Patiala.

An administration backed by over 80,000 uniformed men, including the army, BSF, CRPF and the state police force now kept its fingers crossed, with survivors of clashes in Delhi and elsewhere trickling into the state and describing their travails at the numerous gurudwaras.

If the state has so far reacted to the happenings elsewhere with restraint, it is a tribute to the traditionally harmonious relations between the two communities in the rural areas. Even at the height of the Bhindranwale wave there had been no case of Hindus and Sikhs clashing in the villages and it is the same old bond that has prevented clashes so far.

But officials fear that the renewed tension may be just too much even for these ties to withstand. In the cities, in any case, the two communities, particularly in the business areas, have had a history of mixed relationships. And that is where tensions are seen currently.

“We are keeping our fingers crossed,” says Director-General of Police K.S. Dhillon, adding, “we cannot rule out reaction among the Sikhs after their fellow beings arrive from other parts of the country.”

Initially, the news of the assassination had caused some jubilation among the Sikh population. In fact, the police arrested 17 students from professional colleges in Ludhiana, 13 in Jalandhar and five in Patiala for distributing sweets.

For many Sikhs, Mrs Gandhi had only been “executed” for her “sins” against”their community, particularly the storming of the Golden Temple in June.

The immediate reaction among the Hindus was that the leader who protected them had gone away from the scene, leaving them insecure. But subsequent developments in Delhi and elsewhere had a chastening effect on everyone.

As senior Sikh jurist Dara Singh says: “It was a senseless, inhuman act. But what followed Mrs Gandhi’s assassination is equally condemnable. Killings solve no problems.”

As the initial shock wears off, the situation remains explosive. Unfortunately, the Government has made very little effort to defuse it except for the governors’ appeals broadcast on radio and television. It relies almost entirely on a strong, all-pervading military presence.

The Sikhs tend to blame the violence on the Congress(I) and their anger hasn’t spilled over to the Hindu community. Some Congress(I) functionaries have also reacted with timely intervention. Hindu Suraksha Samiti leader Pawan Kumar Sharma visited Chandigarh shortly after the assassination, stayed with Union Law Minister Jagan Nath Kaushal and tried to organise processions.

But Kaushal firmly prevented him from doing so. Initially, as trouble broke out in Delhi the administration had reacted in the same way as during the Bluestar exercise, blocking all traffic in and out of Punjab, stopping rail services and frisking all those entering the cities. Columns of heavily armed troops were sent on long patrols into the countryside and night curfew clamped in sensitive areas.

With the population still apprehensive and shocked, a formidable obstacle on the road to normalcy is the stringent press censorship enforced by the Government. With newspapers and magazines from outside the state banned, people have no choice but to listen to rumours and foreign radio broadcasts, particularly the British Broadcasting Corporation.

As the editor-in-chief of The Tribune and president of the Editors’ Guild Prem Bhatia says: “The havoc which the censors have caused will have its repercussions in the course of time …Junior officials of the rank of head clerk and office superintendent have been entrusted with the job of censoring newspapers.

Clothed in brief authority and with their limited vision they are handling their serious responsibility in a manner for which the Government will have to pay a heavy price.”

For the moment, however, the situation in Haryana has been more worrisome. Despite Chief Minister Bhajan Lal’s boast that peace prevailed in the state Haryana notched up a toll of over 50 dead in four days of violence. The worst hit were the trains approaching Delhi, particularly from the direction of Uttar Pradesh.

The small towns of Hailey Mandi and Palwal outside Delhi saw repeated, brutal attacks on the trains and accounted for the bulk of the death toll. Many of the injured were removed to hospitals in Delhi.

At the casualty wing of Ram Manahar Lohia Hospital, Serjbeet Singh, a transporter who boarded the Western Mail to Delhi at Baroda cantonment two days earlier, said he was pulled out by hysterical mobs at Tughlakabad station outside Delhi.

“They came with lathis and iron rods and stones and repeatedly attacked all the Sikhs on the train. They stopped the train as many as 15 times before it pulled into Delhi.”

Twelve towns, including Gurgaon, Faridabad, Rewari and Sonepat were placed under curfew while heavy patrolling prevented further outbreaks of violence. Schools and colleges were closed all over the state for 11 days and bus services reduced drastically.

With the initial frenzy over, the shape of things to come in Haryana will depend on how things develop in Punjab which, indeed, holds the key to the communal situation in the country in the months to come.

Also read: Kamal Nath’s ‘role’ in 1984 riots: Has politics helped or hurt victims’ families?

Madhya Pradesh — Extensive loss

The backlash of anger that followed Mrs Gandhi’s death took a toll of over 87 lives – 22 in Indore, which was the worst hit, 12 in Morena, and spread across practically every district of the state.

In fact, of the state’s 45 districts, only two – Panna and Dhatia – were unaffected by either violence, curfew or prohibitory orders. Around 11 people were killed in army or police firing, and350 injured, including nearly 80 policemen. A total of over 6,000 were arrested statewide.

The most shameful incident of mob violence took place at Morena, 35 km from Gwalior. Angered by a rumour – which turned out to be unfounded – that a wealthy Sikh set upon by a mob had killed 18 of them, a crowd 10,000-strong collected near the outer signal of the railway station at noon.

They first stopped the Utkal Express going towards Delhi, but found no Sikh passengers in it. Almost immediately, the Chhatisgarh Express from Delhi steamed in and was brought to a halt by the mob. They dragged out two dozen Sikhs and slaughtered 12, including a ticket examiner.

In Gairatganj, 90 km east of Bhopal, a procession of a few hundred people shouting slogans against the UK-based Khalistan protagonist Jagjit Singh Chauhan was fired upon by a Sikh hotelier whose house lay on the procession route.

Two people were injured, and one subsequently died. The police laid siege and later entered the house to find that the man had shot his family of four and killed himself as well.

In Indore, where the police had anticipated trouble and prepared for it, they were able to prevent a mob attack on the Imli Sahib Gurudwara on October 31.

But the following afternoon, in the words of district collector Ajit Jogi, “Everything exploded – it seemed the city’s entire population was out on the streets.” Almost simultaneously, 62 cases of arson were reported as phone calls swamped the town’s fire stations.

The historic Rajwada Palace, built in 1754 by Malharrao Holkar was destroyed by fire that spread from nearby shops that had been set ablaze, and firemen fought it for nearly two days. A loss of over Rs 1 crore has been estimated. Citizens are suspicious because the violence followed a pattern – the property of Sikhs known to be close to the Congress(I) was mysteriously spared.

And it wasn’t the grief and anger at Mrs Gandhis death alone that incited the mobs. Crowds of people were seen breaking into homes and hotels and helping themselves to everything from liquor and watches to refrigerators, cutlery and beds.

But in the midst of the madness, there was a good deal of sanity as well. Preetam Singh Chhabra, general secretary of the Guru Singh Sabha at Indore and his family found shelter at the home of their Hindu friends. Iqbal Singh, a Sikh transporter, said: “If my friends had not helped me, I would not be here before you.”

Bihar — Tragic toll

In terms of both enormity and brutality, violence in Bihar was next only in intensity to that in the capital. The three-day frenzy claimed no less than 200 lives though the Government placed the toll at a not-too-modest 108.

The wave of killings abated only after as many as 15 towns were placed under curfew and the army called out in seven.

What began as a spontaneous outburst of anger was allowed to turn into an organised campaign of crime against the Sikhs. Even before large-scale killings began in Delhi, riots broke out in the steel town of Bokaro claiming 60 lives.

In several cases the marauding mobs were led by leaders of the Congress(I) and its youth wing. The suspicion was more than confirmed when Chief Minister Chandrashekhar Singh personally ordered the police to arrest a Congress(I) worker at Patna Sahib, Guru Gobind Singh’s birth place.

A witness to the carnage, DMKP leader Roshan Lal Bhatia, alleges that the whole operation was led and masterminded by Congress(I) Seva Dal volunteers, the Youth Congress(I) and the police. “For two years,” he says, “Seva Dal volunteers have been trained on the RSS pattern and they have put their expertise to use now.”

Even worse than the Congress(I) culpability was the apathy of the police. In the thick of it all, a senior police officer let slip in an unguarded moment the observation that what was happening was a “natural” reaction.

Sikhs who sought refuge at Takht Harmandirji gurudwara told the chief minister that the police refused to register complaints against a Congress(I) worker leading the mobs. Often, the police reacted quickly to the rumours – all false – of Sikh retaliation while taking the reports of anti-Sikh rioting in its stride.

In too many instances the army was seemingly called out only on paper. It staged flag marches and just disappeared without resorting to any action. This was particularly so in Patna where the troops were hardly allowed to get out of the trucks before being given the orders to return to their barracks.

This mysterious invisibility seems rather inexplicable though it is possible that a hard-pressed army needed to use the units elsewhere.

Not surprisingly, chaos reigned in the state, with the police not bothering to enforce curfew for two crucial days. The fact that the chief minister had “air-dashed” to Delhi on hearing of Mrs Gandhi’s assassination did not help either.

By the time he returned to his state on Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s instructions, as many as 60 people had died in Bokaro, 10 each in Dhanbad and Ranchi, 12 in Daltonganj, six in Patna, three in Jamshedpur, four in Jhumritilaiya and one each in Hazaribagh, Muzaffarpur and Bhagalpur.

In the three days of practically unfettered violence, only seven people were killed in police firing – the rest had died at the hands of mobs.

Also read: Why Jungle Raj Bihar kept out communal riots for 3 decades but Delhi and Gujarat couldn’t

Uttar Pradesh — Police apathy

With its history of Nirankari-Sikh clashes, Kanpur has always been considered a town vulnerable to communal acrimony.

And in the current round of madness this industrial town alone accounted for nearly 40 per cent of the total death toll in Uttar Pradesh, which was put conservatively at around 140. As many as 29 died in Ghaziabad near Delhi.

Most grotesque, a local train that stopped in Maripat station 12 km from the industrial suburb east of Delhi was found to contain nine bodies, according to the Superintendent of Police B.P. Chakravarty. In Lucknow city itself at least five Sikhs were killed in one single incident of organised violence that took place at Charbagh station.

Tragically, the police was to blame for its failure to avert the violence and mass murders that were clearly coming in the wake of Mrs Gandhi’s assassination. For instance in Lucknow, crowds which had been gathering in the Charbagh station since the morning were incited by a rumour that bodies of Hindus slain by Sikhs in Punjab would be arriving on the Punjab Mail.

Though cases of Sikh passengers being attacked by the crowds had been reported to the police since the same morning, no action was taken.

Thus, when the Mail arrived from Amritsar at 3.15 that afternoon, there was no one to stop the slaughter – five Sikhs were pulled out from the train and killed on the platform before the police arrived belatedly on the scene over half an hour later and fired some ineffectual shots in the air.

Far from protecting innocent victims from the wrath of the blood-thirsty mobs, the police were themselves alleged to be harassing the people. A Sikh who appealed for police protection was threatened with arrest instead.

Citizens’ groups supplied police with lists of goondas who had been indulging in acts of loot and arson, only to be rebuked by in different officials. Jail staff found fishing in troubled waters most profitable – in the midst of all the trouble, they were alleged to be taking bribes to permit visits by the relatives of those arrested. Nearly 4,000 people were arrested and curfew was in force in as many as 30 of the state’s towns and cities.

West Bengal — Timely moves

Always known to the residents of Calcutta as a shrine of spiritual dignity, Gurudwara Jagatsudhar was a scene of violent commotion last fortnight.

The quiet was shattered as scores of young thugs attacked it with burning torches and iron rods, broke up furniture on the ground floor and burnt parts of the shrine. But the Calcutta police did not repeat the record of their counterparts elsewhere in the country and arrived in time to prevent killings.

The mob was quickly dispersed and as a deterrent to more mischief by armed thugs, a strong BSF picket was posted at the gurudwara. This was an effective deterrent for the mobs who later found the shrine, in which over 800 refugees from other affected parts of the city took shelter, a tempting target.

Indeed, the situation had looked grim on the day of the assassination as Sikh taxi-drivers, who have lived harmoniously with others in the city had the rude experience of being roughed up. In panic, many of them abandoned their vehicles and sought refuge in the police headquarters at Lal Bazar. Elsewhere too, frightened Sikhs sought shelter in gurudwaras or with Hindu friends.

The state Government was quick to overcome the shock – both from the murder and outbreak of violence – and moved fast. Men of the BSF, Eastern Frontier Rifles and even the army were deployed quickly. This ensured that the violence was confined to sporadic attacks on trucks, mostly owned by the Sikhs. No less than 30 were burnt, mainly in the crowded Burra Bazar area.

But conforming to the trend elsewhere in the country the marauders’ motives were more economic and political than communal. For years, the Gujaratis and Marwaris have been trying to muscle their way into the truck trade. The popular fury against the Sikhs appeared as a veritable godsend to them.

Another nation-wide trend was confirmed in the attitude of the Congress(I). Even as parts of the city burnt they carried out processions displaying portraits of Mrs Gandhi and shouting “Death to the killers.” Chief Minister Basu flew in from Tamil Nadu where he was attending a trade union conference and began peace moves.

The Left Front workers took charge of various parts of the city to restore order. Yet, the Congress(I) men kept completely out of it.

In fact, the middle-level leaders only added to the tensions with Subrata Mukherjee and Somen Mitra, the only leaders with some hold over the rank and file of the party choosing to stay on in Delhi during the entire period that Calcutta reeled under the shock of Mrs Gandhi’s assassination.

Maharashtra: Select targets

While Bombay, mercifully, remained quiet, displaying a sense of dignified mourning, trucks were the rioters’ target elsewhere in Maharashtra where mob violence claimed at least 15 lives.

The worst outbreak was in Kopergaon town in Ahmednagar district where, fired by the rumours that a Sikh truck-operator had been shooting indiscriminately, a mob surrounded his house, dragged out three persons and dumped them into burning trucks.

The police arrived on the scene and fired heavily, killing two persons. But not before a score of shops, 22 trucks, a car and two scooters were burnt by the mobs.

In Shrirampur in the same district, the toll in terms of houses was higher – 33. Kishan Sharma, an AIR announcer was mobbed by hundreds of people who asked him why he had continued playing film songs on Vividh Bharati even after Mrs Gandhi’s death.

Maharashtra also accounted for perhaps the only attack on someone connected with the Congress(I). In Aurangabad, the wife of Union minister of state for information and broadcasting Ghulam Nabi Azad was pulled out of her car on her way to the airport. Though she wasn’t harmed, the vehicle was then set on fire.

In Bombay, the two bandhs on Thursday and Saturday passed off peacefully and the Sikhs showed maturity in staying out of the way. Large police detachments guarded the Sikh and Punjabi dominated area of Sion-Koliwada. But there were scores of taxis parked there whose Sikh drivers preferred to stay indoors.

“We feel no fear at all,” said Guru Prasad Singh, the head priest of the Bhai Joga Singh Gurudwara at Koliwada, though a bit nervously. But he added:’ ‘God bless her soul. It is a tragedy not only for the Hindus but for the entire country. We have no fear. We are Indians and we will stay here.”

One consequence of this senseless, sectarian violence was the hike in prices of vegetables, since most truckers who haul these up into Bombay from Pune and Nasik are Sikhs, and they, not surprisingly, refused to drive. But that was minor discomfort compared to what the sprawling metropolis was spared.

—With Coomi Kapoor, Raju Santhanam and Sunil Sethi

Also read: 4 commissions, 9 committees & 2 SITs – the long road to justice for 1984 Sikh killings