Vote shares of major players have remained more or less constant since the Congress lost its domination in 1996. They may have sometimes moved in a narrow band of mostly 2-3 per cent. But changes of government have taken place more as a result of decisive local or regional turnarounds: the decimation of the BJP by the Samajwadi Party (not a constituent of the UPA) in Uttar Pradesh, and the near clean-sweep by the DMK in Tamil Nadu and the Left’s best ever performance in West Bengal and Kerala in 2004 brought the Congress-led UPA to power. The difference in the Congress-BJP vote share was just over 4 per cent. Power changed hands mainly because of several state-level side-shows.

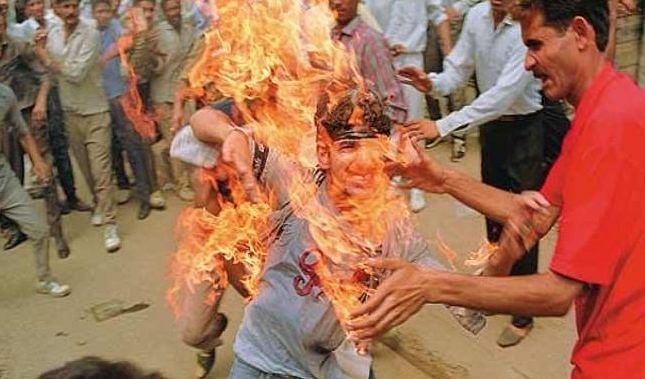

What lost the NDA power was also the loss of its own allies: Naveen Patnaik’s BJD, Mamata Banerjee’s TMC and Chandrababu Naidu’s TDP, all driven out by the Gujarat killings and aggressive anti-minority Hindutva. It was these factors, more than any aam aadmi fightback, or revulsion over India Shining, that brought the UPA to power. In fact the Modi factor, which consolidated minorities against the BJP and drove out any ally with some hope of getting minority votes (Mamata, TDP, BJD), produced a parliament with such peculiar arithmetic that an anti-BJP, Congress-led coalition became the only possibility.

There were changes in 2009, particularly in the cities where some vote shifted from the BJP to Congress, partly because of five years of growth and the rise of Manmohan Singh as a middle class favourite. But essential divisions and faultlines in national politics and voter preferences remained largely unchanged.

You can go backwards to 1996, and find that this status quo has prevailed since then, though three different coalitions (UF, NDA, and UPA) have ruled India. In each election, with such a small gap between the big players, the final power equation has been decided by two kinds of regional players: those who can ideologically or electorally go only with one side (as in the SP and Left with Congress) and those with totally fungible ideologies (DMK/AIADMK) who will go with any front-runner.

Who is responsible for this frozen politics? Our indecisive voters, or our lazy politicians? The answer is, predictably, the latter.

Also read: They just didn’t get it

In the two decades since 1992, no party, coalition or leader has produced a decisive new idea that could influence voters across at least a few electorally important states. We take the 1989-92 period as a watershed because this was the last time a new idea in fact, two checked out the voter’s mind in the Hindi heartland. The BJP launched the Mandir movement in 1989 in earnest and V.P. Singh led Mandalite forces on the slogan of social justice. Both ideas were divisive. But they ensured Rajiv Gandhi’s defeat in 1989 and damaged, almost permanently, the Congress party’s vote banks.

Mandir and Mandal were, therefore, the last big ideas that altered our national power equations. Since then, nobody has been able to catch India’s imagination. Even today, our politics is essentially determined by these two factors. Mandalites rule Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, and across most of the country it is a battle between pro-Hindutva and anti-Hindutva (or more conveniently described as secular and communal) forces.

To that extent, the politics that L.K. Advani and V.P. Singh crafted in 1989-92 still prevails. Surely, specific events (the rise of Vajpayee as an inclusive leader, Gujarat riots, NDA’s sudden parliamentary defeat on the eve of the war in Kargil, and the nuclear deal) cause small, 2-3 per cent fluctuations, decisive in a sharply divided polity. But there has been no big change since 1992.

Democracies and voters respond to big ideas, even during phases in history when elections look like a one-horse race. Indira Gandhi’s aggressive socialism and Garibi Hatao was a big new idea and brought a landslide in 1971, even after she had divided her party neatly in two and her opposition had consolidated. In 1984, Rajiv Gandhi won the Congress its biggest majority ever on his own big idea of youthful leadership and a resurgent, 21st century India.

It is lazy and cynical to dismiss the 1984 verdict as a mere sympathy vote. If that was the case, Rajiv would not have found the kind of popular love and adulation he did in at least his first two years, until things began to fall apart. He was the last leader in India’s history to present us with an optimistic, aspirational and can-do agenda, and was rewarded. He was followed by Advani and V.P. Singh with their mandir and Mandal. Since then, our politics has drifted.

Also read: The out, their rage

Both the Congress and BJP have lacked the courage or the foresight to seize opportunities that came their way subsequently. A Congress government (though not under a Gandhi) ushered in economic reform in 1991. But the party has never gone to the voters with that as a big idea.

So deep is its socialist indoctrination that, in 1996, even Narasimha Rao did not sell reform. I travelled with him on his campaign to Jammu and was astounded when, instead of claiming credit and seeking votes for reform, he told a small, confused audience the story of how he had resisted pressure to privatise his PSUs or allow FDI in insurance. Maine bol diya, he said, main apna LIC kabhi kamzor nahin hone doonga. (I told them, I will never allow my LIC to be threatened). Until the pro-FDI rally in Delhi last November, the Congress had never even talked of economic reform as a major idea.

The BJP’s inability to learn from Vajpayee’s success represents comparable lack of political imagination. Vajpayee showed his party the benefits in moving closer to the ideological centre, of more inclusive politics, which persuaded even a Farooq Abdullah to stay in the tent. He thought, and wisely so, that a new, genteel, non-threatening right-of-centre politics could be built around widespread anti-Congressism in the states. But he was defeated when the party and its ideological controllers held back his hand during the Gujarat riots. This not only lost the BJP its secular allies, it also led to a very slow but consistent decline in its vote share: nearly seven per cent from its 1998 peak.

In the first post-Ayodhya election in 1996, the Congress’s vote share was 28.8 per cent and in 2009 it was 28.55, even though the first time it lost power and the second time it was acknowledged to have won an impressive victory. In exactly the same period (1996-2009), the BJP’s vote share moved from 20.29 to 18.8 per cent, an insignificant decline of just over 1 per cent. Do we need more evidence that our politics has remained essentially frozen for two decades? It also follows that this may just present a perfect opportunity for somebody with the political intellect and courage to break the stalemate.

Also read: The chief in chief minister