Bengaluru: As India tested its anti-satellite missile, or A-SAT, Wednesday, early criticism mounted over how much space debris it would have left behind in the wake of operation ‘Mission Shakti’.

In a FAQ statement issued by the external affairs ministry, the Modi government said the test was done in lower atmosphere to ensure that there was no space debris.

“Whatever debris that is generated will decay and fall back onto the earth within weeks,” said the statement.

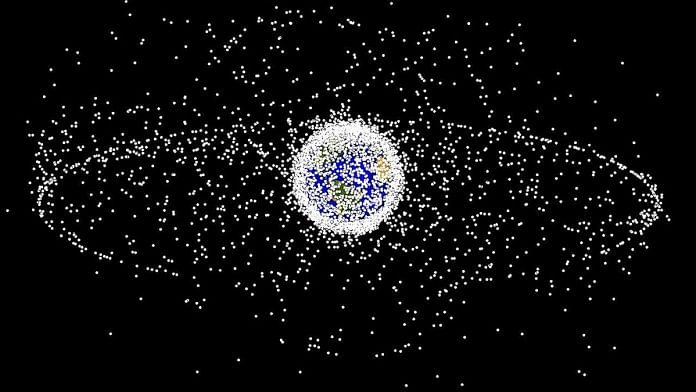

As humankind scales greater heights in outer space with exploration of new bodies and launches of hundreds of satellites, and countries like India look to develop ‘credible space deterrence’, ThePrint takes a look at the issue of space debris staring the human race.

Also read: India’s A-SAT missile strike added to space debris like Kanpur adds sewage to Ganga

What is space debris?

Space debris is the junk left over from any object sent into space, revolving around the Earth, after collision or dumping — chunks of metal, plastic, carbon fibre, frozen fuel ice, or even a microscopic chip of paint. It presents a clear danger to orbiting craft, and at levels very disproportionate to their size.

Since there is neither gravity nor atmosphere in orbit, the motion of these particles is completely unchecked, and something the size of even a brick could potentially destroy something as big as the International Space Station (ISS).

Space debris also travels across orbits. This means that a piece of trash doesn’t remain in the same orbit its source craft was, but can start revolving either higher or lower, or in a more circular or elliptical orbit.

It can be present in the low earth orbit (LEO, below 2,000 km) and can also be present all the way up to 35,000 km up in space. Consequently, the creation of space debris, whose spread can often not be predicted with 100 per cent accuracy and accountability, poses a threat to all objects currently in space and thus evokes concern from all space-fairing nations.

With India testing ‘Mission Shakti’ Wednesday, the international community expressed concern in two primary areas: Geopolitical escalation and space debris.

What creates space debris?

When junk in space is pictured, one imagines parts of metallic frames of broken up satellites floating around, ready to hit a speeding station in orbit. This is, of course, true; so far, six satellite collisions have created waste currently floating in space.

However, there is also intentional junk left there by humankind in the form of rocket stages and accidental trash like Ed White’s glove, Sunita Williams’ camera, a thermal blanket, a box of tools, garbage bags, a Russian toothbrush, and more. Additionally, there is also natural debris like meteoroid particles.

Satellites breaking up into pieces perhaps produce the largest amount of space junk — each satellite could potentially break up into thousands of pieces.

Depending on where the satellite orbits, these pieces either remain in orbit or fall down to the atmosphere and burn up. When they remain in space and something does manage to hit another satellite, the second satellite might potentially break up into thousands of tiny pieces, perpetuating the cycle.

For instance, in 2009, a defunct Russian satellite collided with a functioning US satellite, causing 2,000 more pieces of large debris fragments. China’s infamous 2007 A-SAT test added about 3,000 pieces to space.

This kind of runaway build up of space debris by satellite destruction is called Kessler Syndrome.

Even discounting the extreme incidents, these pieces could still cause serious damage without destroying a craft. In 1996, a French satellite was hit by debris from a French rocket a decade earlier.

Even US space agency National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) had had to replace the windows on a number of space shuttles earlier because flecks of paint that are orbiting at 30,000 kmph damaged them.

As of today, there are over 20,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than the size of a tennis ball and more than 500,000 pieces larger than a marble, according to NASA. All of these are being tracked, while there are thousands more that are too small to detect and pose great risk.

Also read: India set to develop ‘credible’ space deterrence after A-SAT test without fear of sanctions

Mission Shakti

There isn’t much information yet on the debris generated by India’s A-SAT test, but it would certainly have added hundreds of waste particles to low earth orbit.

The one saving grace, as mentioned in the ministry statement, is that the ‘kill’ took place at a very low orbit, in the range of low earth orbits.

At a height of less than 300 km (Microsat-R, the satellite reportedly shot down, orbited at 260 x 285 km), the orbit is within the threshold of 400 km, where there is a large level of assurance of nearly all pieces of debris falling into atmosphere and burning up.

To ensure this would require angling the attack in such a way that no piece escapes to a higher orbit, away from the direction of the atmosphere. This requires the impactor to collide head-on, thus reducing the satellite’s energy and preventing pieces from flying all over the place.

The controlled destruction would enable the debris to slowly deorbit and fall into the earth.

This is exactly what India did.

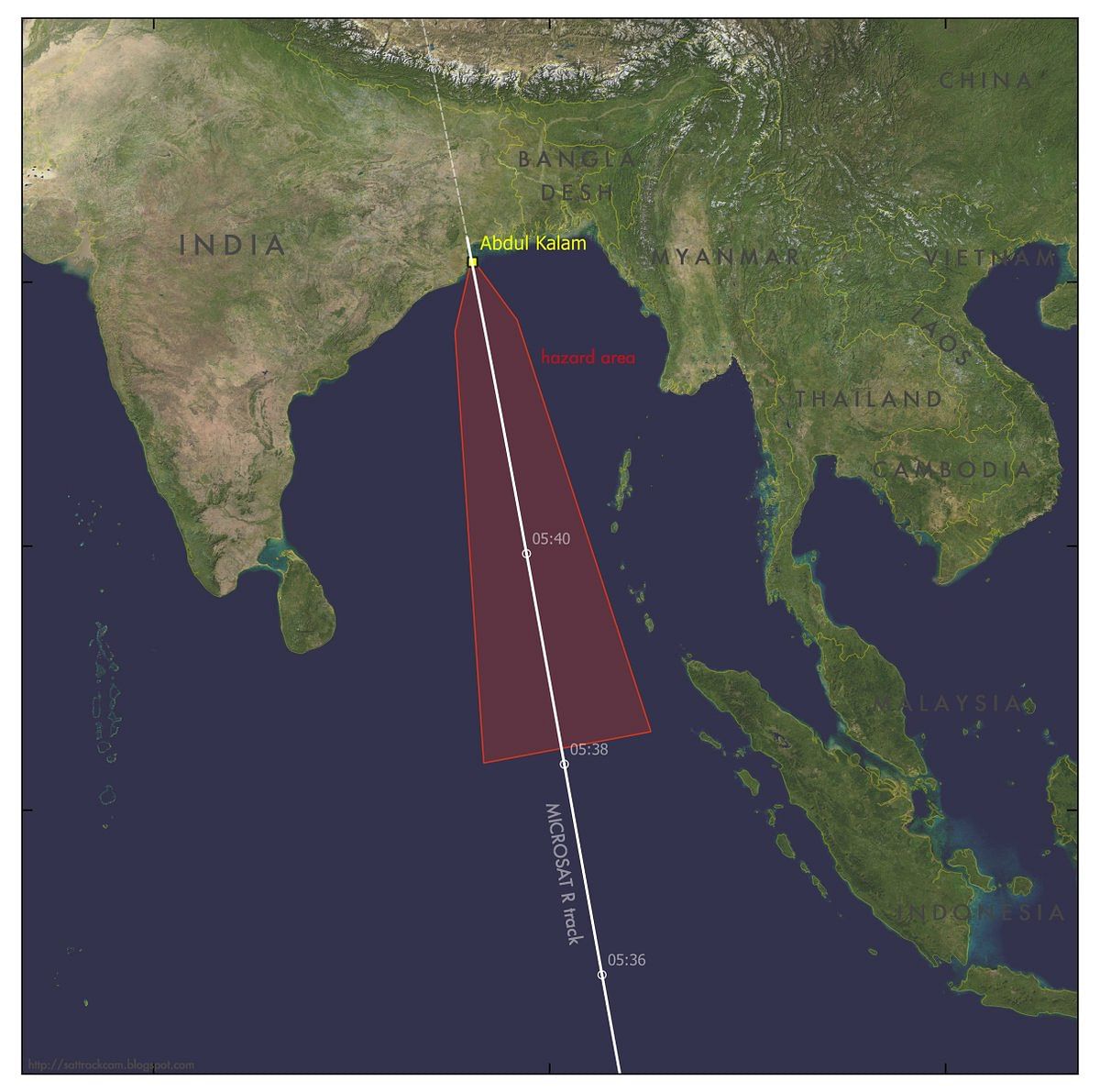

The image above shows the path of Microsat-R during a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) window, when aircraft are warned of impending danger in the area.

It is obtained by plotting the coordinates from the Maritime Area Warning for “hazardous operations”. It shows the path taken by the satellite and the elongated, conical harazard area for debris. The white line indicates the satellite’s path, traveling south to north. The red zone is danger area for the missile and for debris. Only a head-on collision would have an equidistant area of danger on all sides of the satellite. The impact of India’s A-SAT would have occurred at 11.10 am.

There is no way to be certain that the debris is 100 per cent contained. Similar operations in the past have shown that there is inevitably a stray piece that goes astray.

Operation ‘Burnt Frost’ conducted by the US destroyed a defunct spy satellite in 2008, which was orbiting at a similar height of 242 km x 257 km. While nearly all of the debris re-entered and burned up within a few months, a couple of pieces were ejected to higher orbits and remained there for 18 months, before burning up.

This part of LEO is sparse, and not a lot of satellites orbit here. The ISS orbits at 400 km, and most other satellites orbit higher.

So even if there is any bit of debris left from ‘Mission Shakti’, or if a piece climbed higher, the risk emerging from it can be thought to be very low, but not zero.