Boston: “…Lekin pehle de do mera paanch rupaiya baara aana.” Do Bigha Zameen.

The first instance quotes lyrics from the peppy Chalti ka Naam Gaadi (1958) number brought alive by the vocals of Kishore Kumar and Asha Bhosle (and Madhubala’s expressions). The second is the name of one of Bimal Roy’s most well-known movies about the struggles of a farmer.

Baara aana. Do bigha.

Everyone knows now that one rupee is 100 paise, but there was a time when a rupee comprised 16 aana, with four paise to each aana.

Bigha is an old unit for land measurement still in use in pockets of India, but one without a standardised definition. Simply put, a bigha would evoke a different definition in Bihar from what it would in Bengal. Thank God for the acre, right?

The first day of April marks an important anniversary for India — it is the day a population freshly free from the curbs of two centuries of colonial rule put its weight behind a system that would help them keep measure as one, and more simply.

Monday, 1 April 2019, marks 62 years since India accepted the 100-paise-to-a-rupee formula, or the ‘decimal coinage system’, setting the stage for the adoption of several other, more standardised measures across the country in subsequent years.

Here, ThePrint takes you through India’s journey to a unified measurement system, which took us from tola, bigha and furlong, to grams, acres and kilometres.

‘All is vague’

In colonial India, one had to grapple with a vast array of measurement systems. Some locally-used units of measurements were based on ancient Hindu metrology. Others had their origin in the Mughal Empire, which in turn had roots in the Persian and Hebrew systems of calculating weights and measures.

These systems of measures varied from commodity to commodity, and place to place. James Prinsep, a 19th-century antiques enthusiast and colonial administrator deployed in India, wrote in his book Coins, Weights, and Measures of British India that Indian measurement systems were “localised in a thousand distinct foci under as many modifications”.

“Here all is vague,” he added.

The need for a standard system of weights and measures was evident to the British. In 1870, the Indian Weights and Measures Act led to the adoption of the British imperial system as the common metrological language of the country.

However, while the imperial system was used for all official transactions, myriad localised systems remained in vogue. And because there was no easy way to convert between the local units and the imperial ones, the true meaning of a measurement was often lost in translation.

This attempt in standardisation thus proved to be a half measure.

Also read: The kilogram is being redefined – a physicist explains

A French connection

The problem of nonstandard units of measures was not unique to India.

France, in the late 1780s, had nearly 800 units of measures. This made taxation and trade so cumbersome and rife with fraud that it was one of the precipitating factors for the French Revolution.

During this turbulence, a group of scientists at the French Academy of Sciences developed a new measurement system based on the natural world “for all people, for all time”. They called this the metric system.

The unit of length in the metric system — the metre — was defined as one ten-millionth part of a quadrant of the earth’s meridian that passed through Paris. The unit of mass — the kilogram — was defined as the mass of water that had a volume equal to a cube whose sides were one-tenth of a metre.

The ease of use of the metric system, however, lay in its radix, or base. The metric system had a base of 10. So, all multiples and sub-multiples of the basic units were integral powers of 10, linking the units with the decimal way of counting.

In India, most systems of measures had a radix of four. For example, an Indian unit of weight, the mound, was equal to 40 seers. A seer in turn was equal to 4 paos. This use of base four was evident in Indian coinage as well, as mentioned before.

The metric system’s use of decimal counting held the promise of simplifying calculations. In India, where the number zero and the decimal place value notation were invented, this was viewed favourably.

The Indian Decimal Society, which was founded in 1930, strongly pushed for decimalisation and metrication in India. Its campaign of spreading knowledge and awareness about the metric system was carried out through newspaper articles, debates, and seminars.

When India gained Independence in 1947, the rationale for metrication shifted from facilitating interstate commerce (a colonial objective) to economic planning (a nationalist objective).

By the mid-1950s, India was ready to embrace its more ancient past of decimalisation and sever its ties from the imperial system.

‘Silent revolution’

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, was aware of the difficulty associated with metrication.

“[I]t is not very easy to change old-established customs,” he wrote in the foreword for Memorandum on the Introduction of Metric System in India. “But I am sure that our decision to adopt the metric system is the right one from every point of view.

“On April 1, 1957, a silent but far-reaching revolution is going to begin in India,” Nehru said, in a message to the people. “This is the introduction of decimal and metric system in our coinage.”

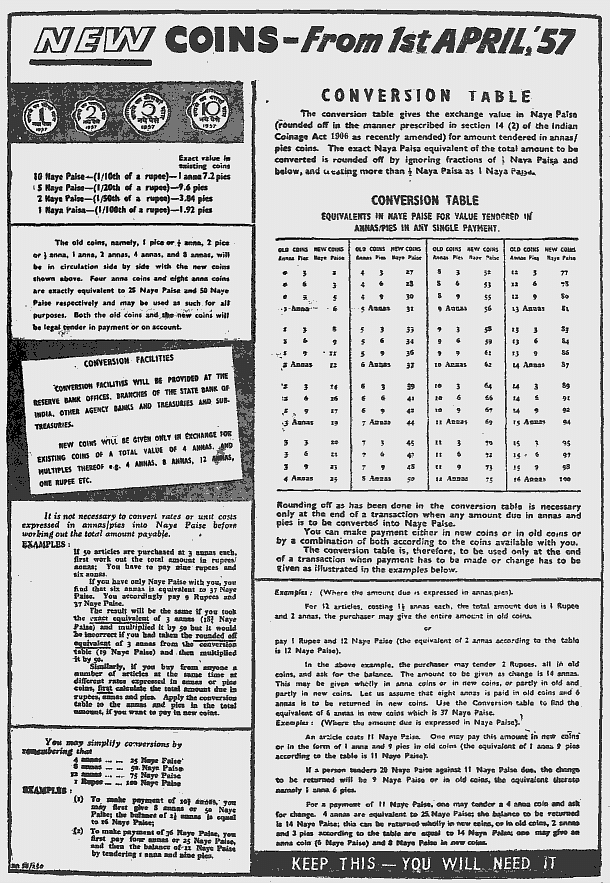

The coinage in use at the time, where one rupee was equal to 16 aana, was phased out. In the new system, one rupee was equal to 100 paise. To distinguish the paise in the old and new systems, the new coins were termed naye paise (literally, new paise).

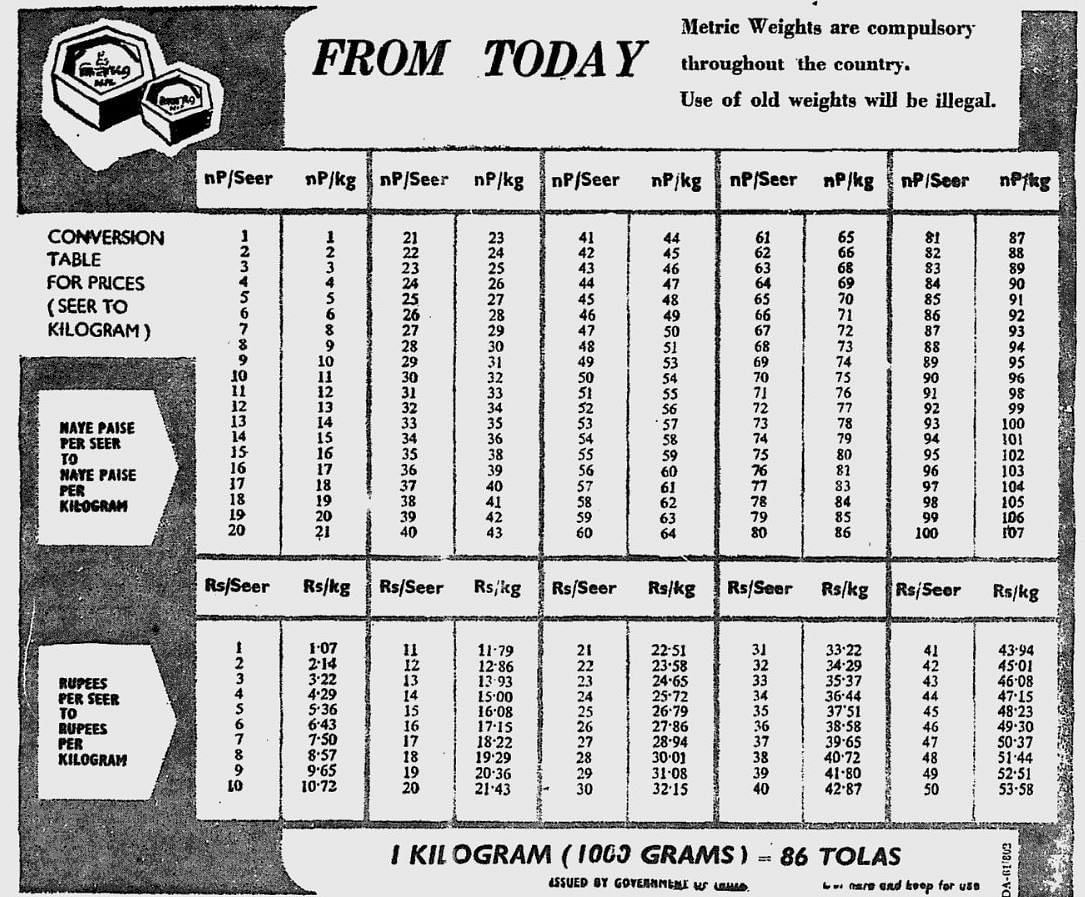

From 1 April 1962, the use of metric weights became mandatory. This was followed by the metrication of measures of lengths on 1 October 1962, and mandating the use of the litre on 1 April 1963.

The introduction of the metric system in India came to be seen as an exercise equivalent the big bang, implying the quick pace.

The changeover involved the replacement of millions of weights, measures, and associated equipment.

India became the first Commonwealth nation to go metric, leapfrogging even the British. This reform was so successful that the government of India fielded enquiries from various countries exploring metrication.

“In India the adoption of the metric system […] served as a powerful force for national unity,” then prime minister Indira Gandhi, Nehru’s daughter, wrote in 1969, in the foreword for a book, Metric Change in India, published by the Indian Standards Institution.

“The metric reform is undoubtedly one of the great accomplishments of free India, one which has attracted world-wide notice.”

Over the years, the metric system, now referred to as the International System of Units (or, SI units), has undergone quite a few tweaks and modifications.

The most recent reform redefined four of the base units — including the kilogram — entirely in terms of constants of nature. This redefinition is scheduled to take effect on 20 May 2019, the anniversary of the signing of the Metre Convention, the treaty that created the International Bureau of Weights and Measures.

Also read: Govt to issue Rs 20 coins for the first time, new design for four other denominations

Abhinav Srinivasan lives in Boston and works in the tech industry. You can follow him on Twitter @thexfactorial.

Except the acre is not an SI (metric) unit; stop using the stupid unit and switch to square metres and/or hectares.

This is helpful.