Bengaluru: Of late, the 100-year-old BCG vaccine has received increasing attention, even though it is only partially functional in fighting the disease it was made to battle — tuberculosis. The reason for the excitement is that early analysis patterns in data seem to indicate that in countries that have had mass immunisation programmes with the BCG vaccine, the spread of Covid-19 seems to be slower.

The idea that BCG offers protection against the novel coronavirus, or SARS-CoV-2, seems to stem from the vaccine’s ability to induce something called a trained immune response, where the immune system of someone inoculated against the tuberculosis bacteria grows the ability to fight off other pathogens, including parasites and viruses.

However, experts in epidemiology, immunology, and tuberculosis warn that this correlation might be just that — a correlation. At the moment, there is no evidence that those who have been administered the BCG vaccine have any immunisation against Covid-19. Additionally, experts also caution that BCG, which is administered to children under one year of age, offers protection for only up to 15 years.

To understand whether trained immunity can evoke a response against the novel coronavirus as well, several trials involving BCG inoculation have commenced in countries like the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, and the US, while countries like India and Greece already have ongoing trials for BCG-tuberculosis, which could also be used to obtain data for Covid-19 studies.

Also read: ICMR studying BCG vaccine for Covid-19, won’t advise without enough evidence: Top scientist

What is BCG vaccine?

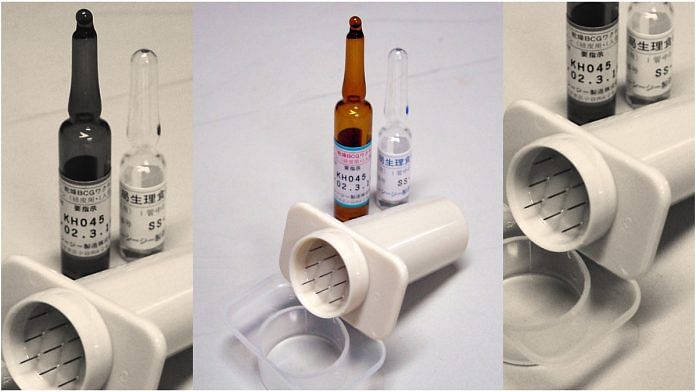

The BCG or bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine is named after French microbiologists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin, who developed it almost exactly a 100 years ago, in 1919, to fight the highly contagious respiratory illness tuberculosis. The vaccine was first used on humans in 1921.

It played a major role after World War II, when in three years, over eight million babies were vaccinated and the typical spread of TB was prevented.

But the vaccine is not perfect. On average, it has an efficiency rate of about 60 per cent in the population. There is a large variation in how children from different countries respond to the vaccination. The efficacy of the vaccine is debated highly even among TB experts, especially since several studies, like the long-term follow up to the largest study in south India, revealed low (for children) to zero (for adults) protection against bacillary pulmonary TB.

The vaccine was widely and regularly used in the Indian subcontinent. India and Pakistan were the first countries outside of Europe to introduce BCG mass immunisation, immediately after Independence, in 1948. However, today, it is proving inefficient against lung TB, the most common form of the disease in India.

There are now studies underway to find a replacement.

A new variation of the vaccine, the VPM1002, is currently being tested for TB in a Phase III study (which means 300-3,000 people being tested for a promising drug) on adults in India. This is the vaccine that will be used to try and fight Covid-19, which is also a respiratory disease.

“What I worry is that countries like India will become complacent on the basis of these weak studies, and not do other urgent public health interventions that are critical for Covid-19,” said Madhukar Pai, Canada Research Chair in Epidemiology & Global Health; Director, McGill Global Health Programs; and a tuberculosis epidemiologist.

“For example, increasing the number of tests for Covid-19 is really critical to know the spread of the virus in the community,” Pai said.

It is unclear whether Indian officials or those anywhere in the world consider it an ideal time for another round of mass BCG inoculation, in preparation for Covid-19.

Also read: A JNU lab is working on a revamped BCG vaccine with Covid-19 protein to fight pandemic

Why the excitement about it?

Humans as a species are notorious for finding patterns where there aren’t any — a phenomenon called pareidolia. It’s what makes us see faces on walls and Virgin Mary on toast. Our skill to identify, or make up, patterns is crucial to survival, because historically, it enabled us to sense or predict the presence of predators. It is also what innately helps babies identify faces and smile back at them.

Pareidolia extends to data as well: People are highly prone to drawing patterns from data. The assumption that event A causes event B simply because they seem to exhibit a pattern of growth together is a logical fallacy. And it is highly prevalent and can be extremely misguided in medicine and public health.

One of the most common examples of this fallacy lies in regression to the mean: Some patients who try alternative therapies for an illness report feeling better after a few days, because the disease naturally runs its course and the body fights back. But this phase of the disease’s cycle coincides with the alternate therapy (which often acts slow), and thus, a pattern is established that seems to point to a working remedy.

Without extended, double blind studies, the evidence for a causation — the alternate therapy causing the illness to subside, or the BCG vaccine actually providing immunity to Covid-19 — cannot be established. Often, the design of a study can also be faulty, such as having too few people, having a sampling bias in the selection of people, or simply having inaccurate data.

Several studies have drawn data correlation between BCG and Covid-19. Two of these, both American, have risen to prominence in the BCG discussion. One is an ecological study conducted by researchers from the College of Osteopathic Medicine from the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT), while the other involves an Indian-American urologist from the University of Texas’s MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The studies were widely covered in the media and reported about as promising and miraculous.

Also read: UV light booth, nasal gel & other innovations India’s working on to battle Covid-19

Why the excitement should be tempered

“Correlations such as these are useful for generating hypotheses,” said Gagandeep Kang, one of India’s leading immunologists and executive director of Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, Faridabad.

“BCG vaccination resulting in a difference in immune responses is feasible, but as yet unproven for SARS-CoV-2. I would like to see an individual level analysis, showing that in Covid-19 cases and matched (i.e. similar age, sex, socio-economic status, location, travel history, co-morbidities, etc.) uninfected people, there is a clear difference in BCG vaccination,” Kang said.

“I would also wait for results from the many randomised controlled trials that are being done around the world to have unequivocal evidence,” she said.

Speaking about the NYIT study, Pai said: “At best, ecological analyses generate hypotheses that can be tested out further.

“It is one of the weakest study designs to make any causal inferences. So, I am really shocked that the authors of the study concluded that BCG might confer long-lasting protection against the current strain of coronavirus.”

The study incidentally used the BCG World Atlas — a database of global BCG vaccination practices and policies compiled by Pai and his group. McGill’s epidemiology research students, in turn, have denounced the NYIT paper. In their criticisms, the McGill research students wrote that the study didn’t take into account factors like lack of data in countries like India (where the disease reached later and Tablighi Jamaat-related cases hadn’t been known yet), conflating population-level exposures to individual-level, biological explanations behind other BCG-related findings, the fact that BCG protects for less than two decades, etc.; and that it drew premature conclusions.

“The study has many limitations that our epidemiology students have captured,” said Pai.

“Lack of testing and under-estimation of Covid burden in many low and middle-income countries, lack of adjustment of confounding by age, doing the analysis too early in the pandemic, etc. If the same analysis was done in May, I would predict the findings would look very different,” he said.

Kang agreed: “Low testing numbers is also a very plausible hypothesis, and we will find out in the next couple of months.” Low testing numbers can often ignore asymptomatic cases, who actually make up a large chunk of the infected.

“Testing has to be done both for acute cases of respiratory diseases and also widespread seroepidemiology to show whether there has been a high proportion of asymptomatic infections,” explained Kang. “The serological tests are unproven yet, but at a population level, will be very useful to understand disease.”

But, perhaps, the biggest argument that could counter this correlation is that countries like China, South Korea, Japan, and Iran, all of which have seen massive numbers of Covid-positive patients, provide BCG inoculation at birth. European countries too have provided BCG vaccinations, including the UK, which did until 2005.

The World Health Organization has also released an advisory this week, announcing that there is no evidence that BCG protects against Covid-19, and that it does not recommend the neonatal vaccination for the novel coronavirus until more data is available from ongoing studies.

Also read: More than ventilators, India needs thousands of coronavirus contact-tracers

Why BCG still offers hope

Vaccines increase the immune response specific to a kind of pathogen, and the antibodies produced by our white blood cells can then bind and neutralise this kind of virus or bacteria. The BCG vaccine contains a weakened strain of the Mycobacterium bovis, a close relative of M. tuberculosis, the microbe that causes TB. But the vaccine purportedly does something more.

There is weak evidence, but some previous studies have shown that the BCG-induced response can actually improve our ability to fight some unrelated viruses as well. It could prevent up to 30 per cent of all known infections, not just from viruses. The vaccine has demonstrated that it can protect against other viral infections of the respiratory tract such as influenza.

These studies have been criticised for not being thorough in their methodology — some reviews have found positive correlation but clarify that more randomised trials are needed, while others find more beneficial correlations like this 2014 WHO review that found that the vaccine lowered mortality rate in children.

But overall, there is enough research being driven into the vaccination and reviews of such research still figuring out how much advantage we could gain.

Even within tuberculosis effects, the BCG vaccine has been seen to ease symptoms relating to breathing difficulties. Studies have found that up to 60 per cent of mortalities from pulmonary TB are not directly related to TB, but due to respiratory infections and complications.

However, as the McGill epidemiologists note in their criticism of the NYIT study, while “a vaccine for an infectious disease of the lungs could also protect against other infectious diseases of the lungs seems somewhat consistent and thus palatable”, this really isn’t so.

They explain that when there was a global shortage of BCG from 2013 to 2015, there was a surge in cases of TB meningitis (of the central nervous system), not really of lung disease or respiratory illnesses.

BCG has also been used as a type of immunotherapy to treat some forms of early bladder cancer, with some evidence of reduction in tumour recurrence and progression.

“BCG does have non-specific immune-boosting properties and works against leprosy as well,” explained Pai. “So, there need to be follow-up studies at the individual level. Indeed, a trial is underway in Australia and I would be keen to see what they find.”

If BCG does turn out to have a protective effect against Covid-19, it would be a medical miracle for a country like India. It is inexpensive, widely available, and can be easily produced by low and middle-income countries.

Also read: R0 data shows India’s coronavirus infection rate has slowed, gives lockdown a thumbs up

Who exactly is / was really excited…except a section of the media?

The bottom line is that nobody really knows.

Portugal and Spain. Two countries in the same region. Same ethnicity. Same climate Similar development state. Two different covid trajectories. Completely different curves.

Portugal gives BCG, Spain does not.

There could be other factors too…. However, too hard to ignore the BCG angle.

It’s a known to any basic Immunologist that BCG vaccine prepared with adjuant(oily) do exhibit cell meadiated immunity that last for the life time

There is a lot of chance that the effect of bcg vaccine for indians who are mostly pre immunized have lower risk of corona virus.

aIs BCG Vaccine for Tuberculosis(TB) also a cure for Corona?

Up to date it’s really cannot be said that BCG would have its effect on Covid19, let’s hope so. But one factor of difference between Euro countries, USA, Australia & China is the Medical facilities, Environment & atomoshere they have & India has, would prove it’s effective role.lets hope would help us