Bengaluru: India will be providing Rs 1,250 crore to the multinational Square Kilometer Array (SKA) project, whose telescope arrays or groups of telescopes will be built in Australia and South Africa.

This week, the Union Cabinet approved the monetary contribution to the international astronomical collaboration involving more than a dozen countries.

Once constructed, the telescopes will scan the skies faster than any previous of its kind, mapping out all visible galaxies up till the edge of the universe, in more detail than ever before.

Survey data from SKA observation will provide deep insights into the early days of evolution of our galaxy, and the telescope will also search for signs of life elsewhere outside the Earth.

The SKA will be built in two phases in both places, with the first phase of construction of SKA1 having begun in December 2022. It is expected to begin operations by 2029.

What is the Square Kilometre Array and what science will it do? ThePrint explains the basics of the project, its significance, and the Indian institutes involved in it.

What will SKA do?

SKA will be a group of radio telescopes operating out of South Africa and Australia in two different ranges of radio frequency. Its headquarters are at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK.

The project aims to answer a wide variety of long-standing questions in physics and cosmology, by observing the universe. It will study the Milky Way in great detail. Since our home galaxy’s view is better from the Southern Hemisphere, the arrays are being constructed there.

Once constructed, the SKA will be the most powerful telescope ever built, and is expected to make unanticipated discoveries of the unknown. It will also be one of the world’s largest collaborative research projects, involving thousands of researchers and the world’s fastest supercomputers.

What are its scientific objectives?

SKA will observe and map galaxies at the edge of the observable universe, going back in time. The telescope will study magnetism and radiation from distant galaxies and map them as well. This will provide details about galaxy formation and evolution.

It will also study the ‘Dark Ages’ of the universe and what happened within a few million years following the Big Bang before there was any light, of which we do not know much.

Through these observations, the SKA will also aim to detect and understand the role of dark matter and dark energy in the universe.

Finally, it will aid in the search for life beyond the Earth by looking for planets that orbit stars in habitable zones and studying their atmosphere for organic compounds, as a part of a science programme called Cradle of Life.

Who is involved in SKA?

Founded in 2019, the Square Kilometre Array Observatory (SKAO) has 16 consortium members — Australia, South Africa, Canada, China, India, Japan, South Korea, the UK, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Italy.

The South-African array will scan for mid-frequency signals, between 350 MHz and 15.4 GHz, while the Australian telescope will work in the low-frequency range of 50-350 MHz.

To improve the accuracy of triangulation of data and its resolution, the project will include additional dishes in the future in neighbouring African countries — Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, and Zambia.

International groups working on technologies will develop technical needs at SKA. These groups are classified into three — Precursors or telescopic facilities built at the SKA site, Pathfinders or an existing remote telescope carrying out research, and Design Study where construction and hardware is being worked upon.

The Indian Pathfinder research partner for the SKA project is Pune’s Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope, operated by the National Centre for Radio Astrophysics (NCRA) of Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). India has also contributed actively to the pre-construction phase of the telescopes as a part of three groups.

The SKA India consortium consists of over 20 colleges and universities across the country that will participate in the SKA project. These include: BITS-Pilani, -Hyderabad & -Goa, IISER Mohali, University of Delhi, Jamia Millia Islamia, ARIES Nainital, Amity University (Noida), IIT -Kanpur, -Varanasi, – Indore, -Madra & -Kharagpur, Presidency University, Indian Statistical Institute, Jadavpur University, Surendranath College, SINP (Kolkata), NISER Bhubaneswar, IIA, RRI, IISc (Bengaluru), CMI (Siruseri), IMSc (Chennai), IISER, IIST (Thiruvananthapuram), MG University (Kottayam), St Thomas College (Kozhencherry), MCNS Manipal, NCRA-TIFR, IUCAA, Pune University, PRL (Ahmedabad), DAA, TIFR, CEBS, and HBCSE (Mumbai),

What will the telescope look like?

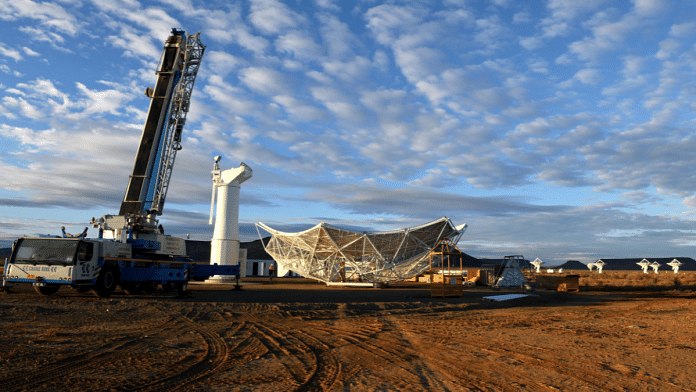

The sites of these arrays will consist of antennae capable of picking up radio signals spread apart over a wide area that is free of radio signals.

These sites will consist of parabolic radio dishes and antennae that look like tall spikes with a bushy end, called dipole antennae. These are capable of detecting faint radio signals from extreme distances. Since the total area of the roughly 3,000 antennas will be about one square kilometer, the SKA was named so.

In total, the SKA telescope arrays will comprise 197 large parabolic radio antennae located in South Africa and 131,072 low-frequency antennae in Australia. The dishes are separated by distances as large as 150 km to help calibrate the origin of observed signals. The 2m tall dipole antennae are grouped together into 512 stations with 256 antennae each. These are separated by distances of up to 65 km.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Sriharikota, we have a problem. The ground is eroding