In a new paper, Thomas Piketty says that a political realignment would move away from traditional notions of “left” and “right,” and pit “globalists” (high-income, high-education) against “nativists” (low-income, low-education).

In a new paper titled “Brahmin Left vs Merchant Right”, French economist Thomas Piketty, attempts to answer two questions: why democracy failed to address the rise of inequality, and why the response so far has been a turn to nativism.

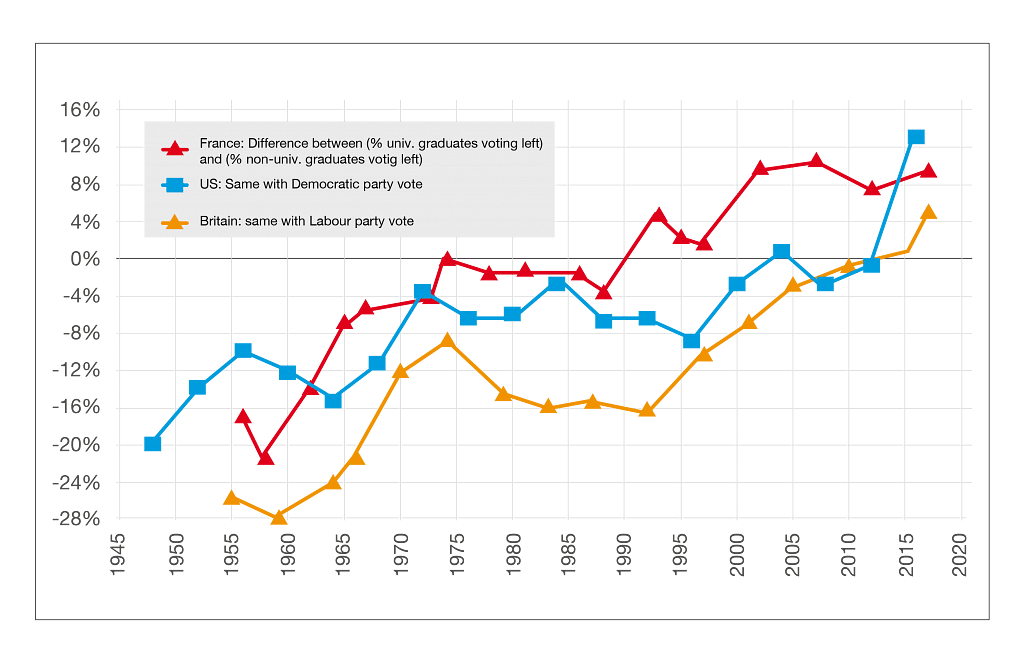

Piketty tracks electoral trends across three countries—the US, Britain, and France—from 1948 to 2017. Despite their vastly different electoral systems and political histories, he finds, a similar trend can be found in all three countries: left and center-left parties no longer represent the working- and lower-middle-class voters they were traditionally associated with.

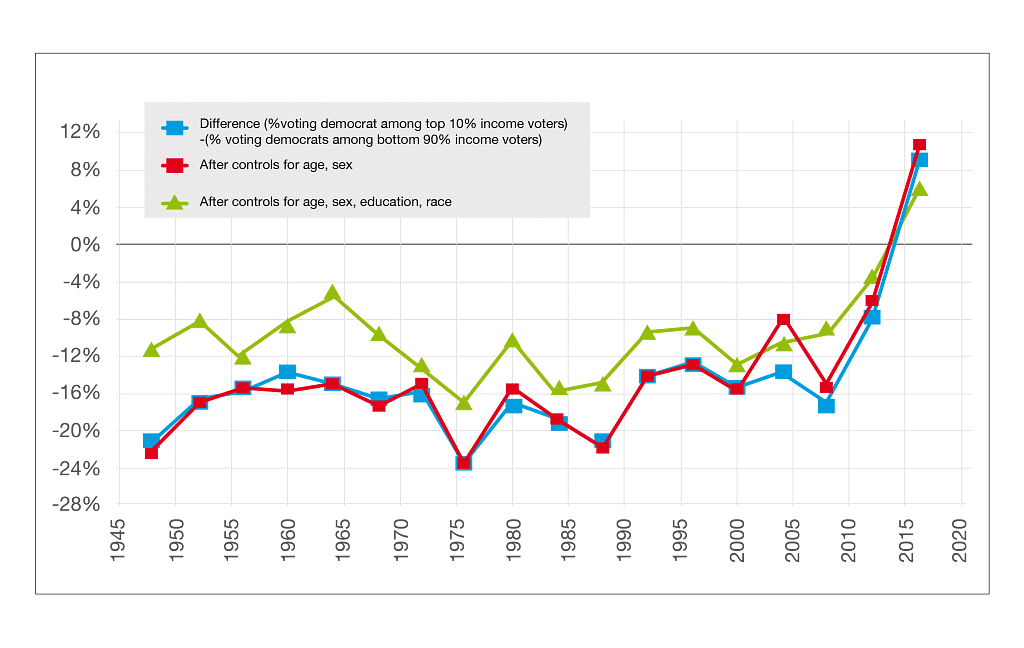

Instead, both the left- and right-wing parties have come to represent two distinct elites whose interests diverge from the rest of the electorate: the intellectual elite (“Brahmin Left”) and the business elite (“Merchant Right”). Piketty calls this a “multiple-elite party system”: the highly educated elite votes one way, and the high-income, high-wealth elite votes another.

With the major parties on both sides of the political spectrum becoming captured by elites, it’s no wonder so many voters feel unrepresented.

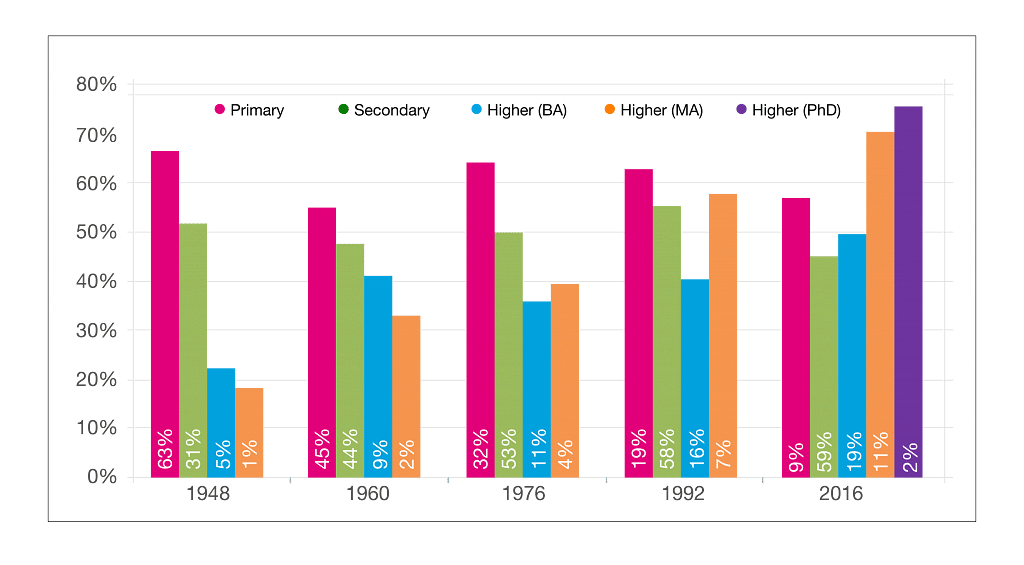

The More Educated Voters Are, the More They Vote for the “Left”

In order to track the evolution of party systems and political cleavages, Piketty uses post-election surveys held in each of the three countries: Britain, the United States and France.

Despite the immense differences in the three countries’ political histories and socioeconomic structures, Piketty finds some striking similarities in the evolution of their party systems. In all three countries, in the 1950s and 1960s, the political system used to be divided along class lines: a vote for left-wing parties in France and Britain, and for the Democratic Party in the United States, was typically associated with low-income, low-education voters. The more educated, wealthier voters tended to vote for the right.

Starting with the 1970s, however, the three countries underwent a similar process of political realignment: the traditionally left parties, which used to be associated with poorer, less educated voters, have gradually become associated with the highly educated “intellectual” elite—as opposed to the high-wealth, high-income elite that still largely votes for the right.

The more educated voters are, he finds, the more they vote for “left” parties: in 2016, for instance, 70 percent of American voters with master’s degrees (which account for 11 percent of the electorate) voted for Hillary Clinton, along with 76 percent of voters with PhDs (2 percent of the electorate). Among voters with bachelor’s degrees (19 percent of the electorate), 51 percent voted for Clinton. Among those with only a high-school education (which account for 59 percent of voters), however, only 44 percent voted for the Democratic candidate.

Even in Britain, the most “class-based” system of the three, university graduates have massively shifted to Labour over the last few decades, particularly those with advanced degrees.

While globalization and immigration have played a big role in the creation of this “multiple-elite” party system, notes Piketty, the process that led to its creation began before these issues became so politically charged, and possibly would have taken place without them. The crucial factor was the growing number of voters with higher education levels, which, he writes, “creates new forms of inequality cleavages and political conflict that did not exist at the time of primary and secondary education.”

Some have criticized Piketty’s study for not giving enough weight to immigration and racism, particularly when it comes to the realignment of Democrats and Republicans in the United States around racial issues. Piketty does acknowledge that the strong support of Muslims in France for left-wing parties and of African-Americans and Latinos for Democrats in the United States cannot be explained solely by variables such as income, education, and wealth, but has to take into account the substantial hostility minorities encounter from the right side of the political spectrum. He also acknowledges that racial sentiments did play a part in driving certain white low-income, low-education voters away from Democratic Party. Nevertheless, he argues, the trend holds: America has become a multiple-elite party system, even when entirely excluding the Southern states.

In France, Piketty finds, the share of voters that oppose immigration has actually declined, from 70 to 75 percent in the 1980s to about 50 percent today.

While evenly split on immigration, French voters are also roughly evenly split on economics, with 52 percent of French voters supporting redistributive measures to reduce inequality. However, these halves are almost entirely uncorrelated, resulting in a “two-dimensional, four-quarter political cleavage” between four groups: the “internationalists egalitarians” (which Piketty describes as “pro-immigrants, pro-poor”), the “internationalists inegalitarians” (pro-immigrants, pro-rich), the “nativists-egalitarians” (anti-immigrants, pro-poor), and the “nativists-inegalitarians” (anti-immigrants, pro-rich).

Globalists vs. Nativists

The 2016 US presidential election, notes Piketty, represented yet another potential political realignment: for the first time, the top 10 percent of voters (based on income) voted Democrat. A similar phenomenon was seen in France’s 2017 presidential elections (Emmanuel Macron’s voters were “highly affluent,” Piketty notes), suggesting that high-income, high-wealth voters were also moving in the direction of the “left.”

This, writes Piketty, could be an anomaly, owing to the unusual nature of the 2016/17 election cycles in France and the United States. But they could also herald something much more significant: a complete realignment of the party system, which would move further away from traditional notions of “left” and “right,” instead pitting “globalists” (high-income, high-education) against “nativists” (low-income, low-education).

Yet this transformation is far from certain. The “multiple-elite” structure could also stabilize—the 2017 British election, notes Piketty, points in that direction. While in France and America there are signs that high-income voters are shifting to the “left,” in Britain there is no sign of this happening anytime soon. In fact, he writes, the last two British elections (in 2015 and 2017) have “reinforced” the multiple-elite nature of the British party system: high-education voters have increased their support for Labour, while high-income voters increased their support for Conservatives.

None of the above two options seems likely to lead to a reduction in inequality, renew voters’ trust that democracy can address their problems, or overcome nativist sentiments. However, Piketty proposes a third possible trajectory, one in which left-wing parties (or nativist parties, though this is less than likely) return to their long-abandoned class-based politics and adopt a powerful progressive agenda focused on reducing inequality through redistribution. Without such an agenda, he argues, politicians would find it difficult to unite low-income, low-education voters and build a wide enough coalition able to counter inequality.

But first, left parties would necessarily have to put an end to Brahminism and convince voters they represent more than the sum of their elite.

This is a shorter version of the article that was originally published in ProMarket.org.The tables have been reproduced with the permission of the authour. You can read the full version here.