New Delhi: A doubting world looked on as India plunged into its “great experiment” in the winter of 1951. More than 10 crore Indians would go on to cast their ballots in the fledgling republic’s first ever general election. In Kendrapara, Odisha, they chose Nityanand Kanungo, Union minister and Congress stalwart, to be their MP. It was the first, and so far, last time — Kendrapara’s voters have never elected a Congress candidate to the Lok Sabha since.

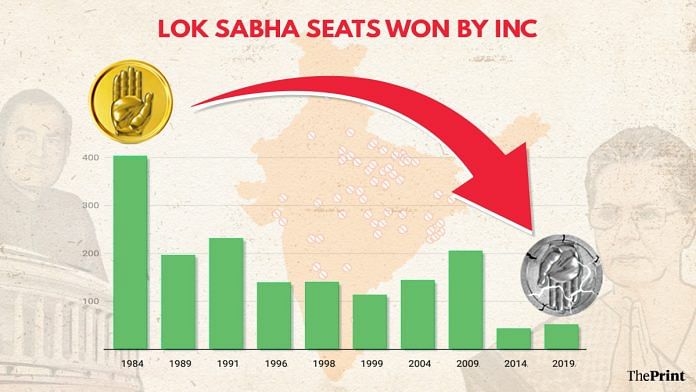

Over the decades, the Congress would proceed to vanish similarly in many other seats, and the trend has been accelerating since 1985 — after Rajiv Gandhi’s 400+ seat sweep the previous year — an analysis of election data by ThePrint has shown.

Experts pointed to no single cause to explain this long-term or “secular” decline, but did cite the rise of regional parties as a major factor.

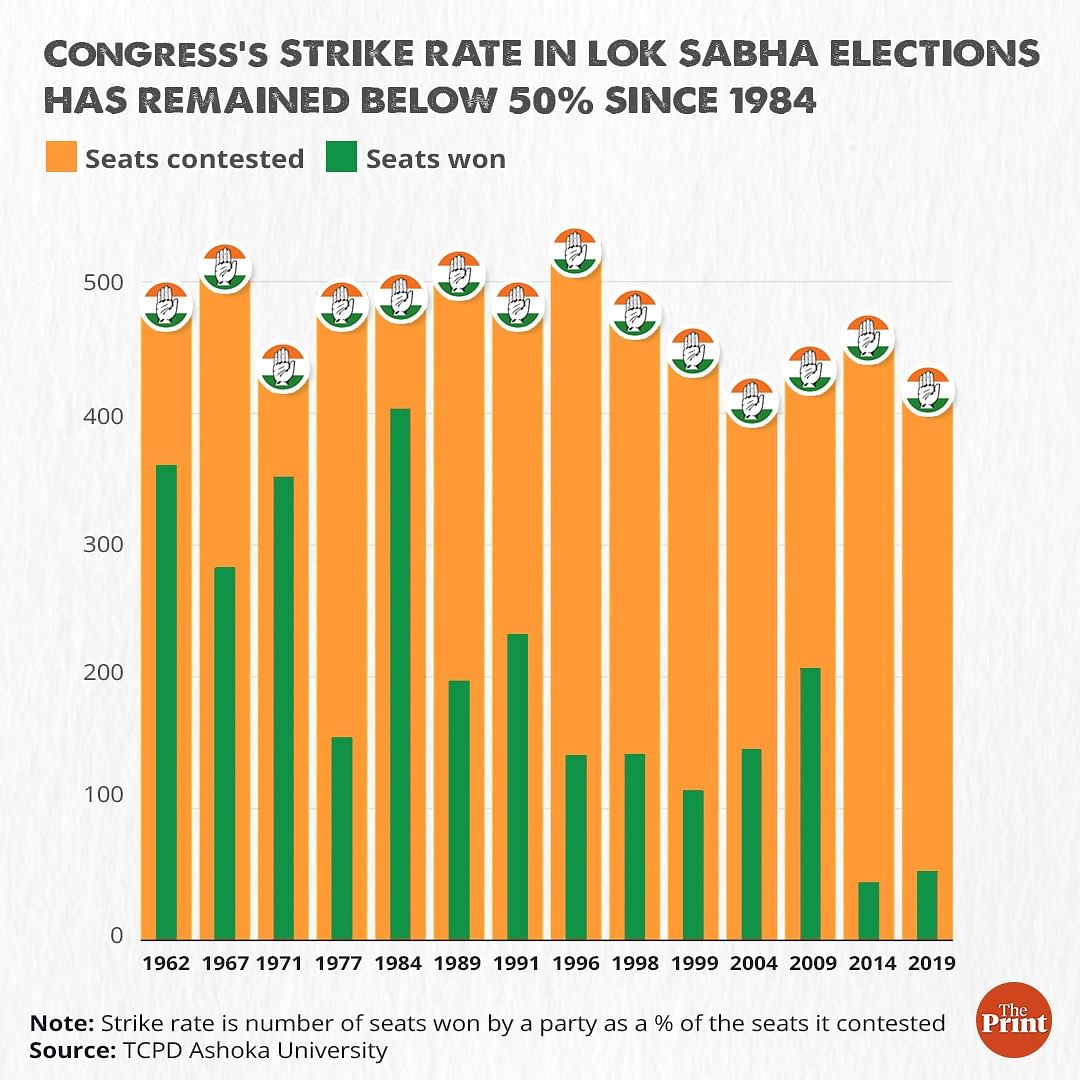

According to data compiled by the Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD) at Ashoka University, from 1962 till 1984, the Congress’ strike rate — the percentage of seats it won out of all those it contested — was above 50 per cent. The sole exception was in 1977 — in the aftermath of the Emergency — when it scored 31 per cent and Indira Gandhi’s government fell.

At its peak in 1984, the party won 404 of the 491 seats it contested (82 per cent). But since then, the Congress has never been able to reach that 50 per cent strike rate.

In 1989, the figure was 39 per cent, and it came closer to the halfway mark in 1991 with about 48 per cent. From 1996 till 2004, the party won hardly a third of the seats it contested on average (29 per cent). In 2004, when the Congress formed a government as part of a coalition, it won 35 per cent of the seats it contested. By 2009, its strike rate had jumped to 47 per cent.

But in 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) swept to power under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the Congress’ strike rate was reduced to 9 per cent. Of the 464 seats it contested, it lost 420 (91 per cent). In the 2019 Lok Sabha polls, the party lost about 88 per cent (369) of the 421 seats it contested.

While Modi’s ascension to the national political centre stage has been attributed as a factor in the Congress’ decline, ThePrint’s analysis of election results shows that the party started losing its sway in a growing number of constituencies long before the so-called ‘Modi wave’ began.

Organisational failures by the party could be a key reason for these defeats, believes Gilles Verniers, co-Director of TCPD, Ashoka University.

“At the state level, organisationally, the Congress party has been at a loss. Of course, local erosion contributes to overall organisational collapse. The strength that the party had, has now been taken over by other parties. Sometimes, even a Congress offshoot has taken over — look at the YSR Congress Party (YSRCP) and the Trinamool Congress,” he said.

Also read: BJP-led NDA now rules 44% of India’s territory, and almost half its population

61 ‘Congress-free’ seats

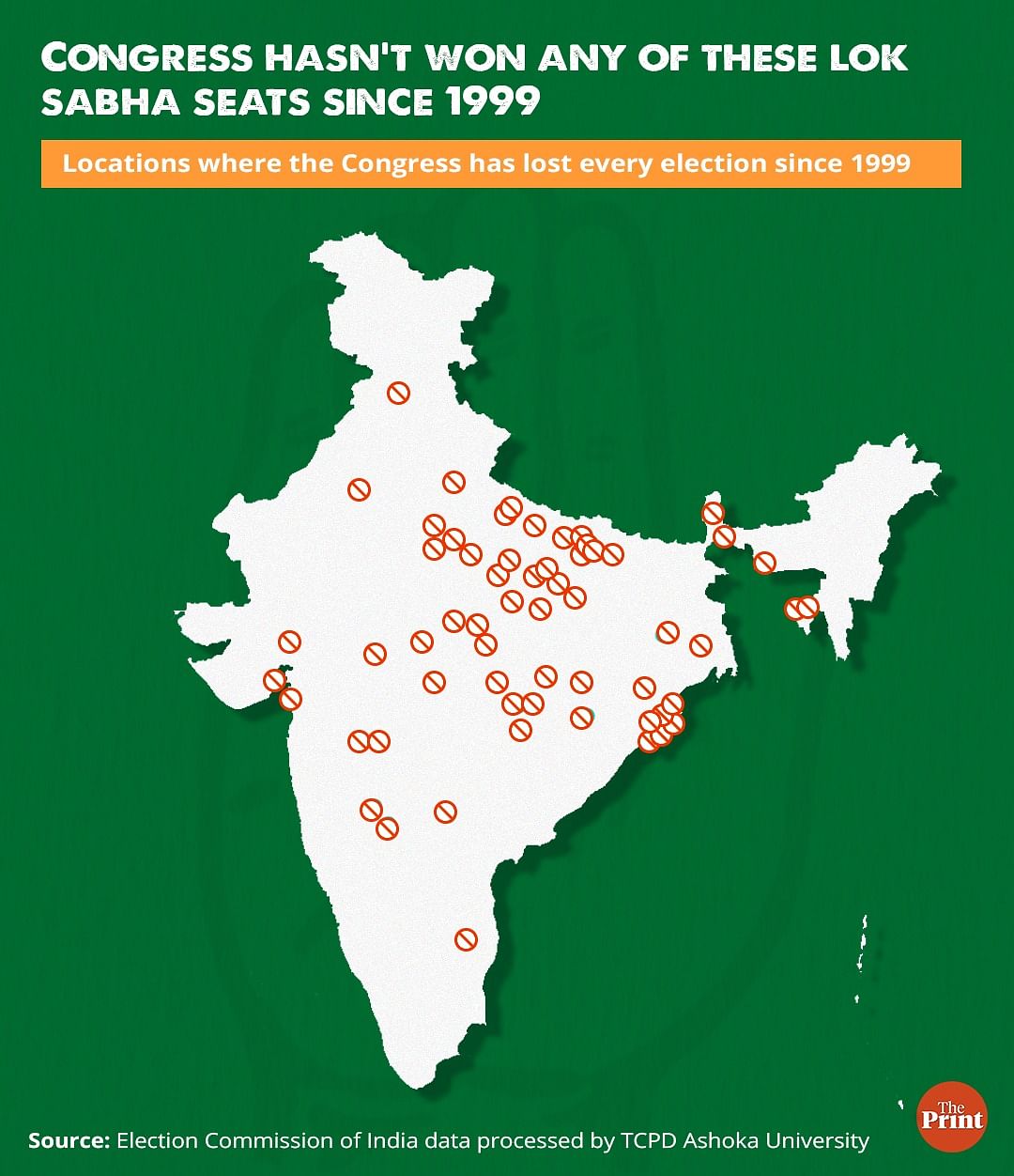

The data reveals many individual seats where the party’s footprint has been vanishing. In the five Lok Sabha elections from 1999 onwards, there have been at least 61 seats where the Congress has contested each time but failed to win even once,

That is to say, voters in 11 per cent of all Lok Sabha seats have been continuously rejecting the Congress for the past five general elections. And this number has increased in each successive election.

While the Congress’ overall tally in the Lok Sabha did go up — from 114 in 1999 to 145 in 2004 and 206 in 2009 — it could never win those 61 seats.

In 2019, the Congress contested in 421 seats and won in 52. In 329 of the 369 seats where it lost, the party had also been defeated in the 2014 Lok Sabha election. In 142 of these 329 seats, the Congress had also lost in the 2009 election.

Going back further, to 2004, reveals at least 93 seats where the Congress has continuously lost in the last four elections. Of these 93 seats, the party had lost in at least 61 in the 1999 Lok Sabha election.

Over half of these 61 seats are situated in the states of Uttar Pradesh (18), Madhya Pradesh (11) and Odisha (8) alone. The rest lie in Chhattisgarh (5), West Bengal (4), Gujarat (3), Maharashtra (2), Andhra Pradesh (1), Telangana (1), Bihar (1) and Tripura (2), Himachal Pradesh (1), Karnataka (1), Meghalaya (1), Rajasthan (1), and Sikkim (1)

By 2019, the BJP had conquered most of these constituencies, but in several states such as Uttar Pradesh, Odisha and West Bengal, it was regional parties that had first taken the seats away from the Congress.

The electoral history of these 61 seats throws up striking details about the Congress’ absence in those areas.

History of losses

For instance, the Congress has never won West Bengal’s Arambagh Lok Sabha seat, which was established in 1967 — Indira Gandhi’s first election, which saw the party’s tally fall by 78 seats. The seat went on to become a Communist Party of India (Marxist) bastion from 1971 till 2009, with the only interruption being a Janata Party interlude in 1977. But in 2014 and 2019, the Trinamool Congress wrested Arambagh from the CPI(M).

Another seat in West Bengal, Bolpur, last elected a Congress candidate in 1967, while Purulia and Jalpaiguri last did so in 1971.

In Odisha, the Congress lost Kendrapara to the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) in 1957. The Biju Janata Dal has held the seat since 1998.

The Congress has never won Sikkim’s sole Lok Sabha seat, except in the state’s first general election in 1977, when the party’s candidate was elected unopposed.

Since 1984, the party has never been able to win the Hyderabad constituency in present-day Telangana. In 1984, Independent candidate Sultan Salahuddin Owaisi, then president of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), won this seat and held it till 1999. His son, Asaduddin Owaisi, has held the seat since 2004.

The Congress has been consistently losing a major chunk of these 61 seats from 1985 onwards. Of the 18 seats it has been losing in Uttar Pradesh since 1999, it has not won 14 since the 1984 general election.

Four Lok Sabha seats in Madhya Pradesh also haven’t been in the party’s kitty since 1984. However, unlike in Uttar Pradesh, where these former Congress constituencies had been taken over by regional parties such as the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and the Samajwadi Party(SP) — and now the BJP — in Madhya Pradesh, the seats were captured by the BJP to begin with.

Apart from these, the Congress last won in Sitapur (UP), Fatehpur (UP), Bhavnagar (Gujarat) and Bangalore South (Karnataka) in 1989. There are 14 seats it won for the last time in 1991, six of them in Madhya Pradesh.

After losing its grip on Tripura, the party has never been victorious in either of the state’s two seats, Tripura East and Tripura West, both of which it last won in 1991.

In the mid-1990s, the party also lost its grip on Odisha. It last won Cuttack in 1995, and Puri, Keonjhar, Kanker, Bolangir and Bhadrak in 1996.

The Congress last won Hamirpur, one of Himachal Pradesh’s four Lok Sabha seats, in 1996. Suresh Chandel of the BJP was elected thrice to this seat in 1998, 1999 and 2004. Since 2009, Anurag Thakur of the BJP, son of former Himachal Pradesh CM Prem Kumar Dhumal, has held the seat.

The party also hasn’t been able to revive itself in the following seven seats, where it won for the last time in 1998 — Churu in Rajasthan, Tura in Meghalaya, Rajnandgaon and Raigarh in Chhattisgarh (then Madhya Pradesh), Jajpur and Jagatsinghpur in Odisha and Aurangabad in Maharashtra.

Also read: Time to save Congress is now. Modi knows that, Gandhis don’t

What experts say

There is no single underlying factor as to why the Congress has been losing, according to Sanjay Kumar, co-director of Lokniti at the Delhi-based Centre for the Study of Developing Societies.

“Sometimes, it’s the demography, sometimes it’s the strong local opponent. The rise of regional parties in the recent past can also be attributed as one of the important factors behind the INC’s decline,” he told ThePrint.

“The Congress party has been able to retain the Muslim voters throughout, but now even they are tilting towards regional parties. Look at the absence of the party in West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Delhi, and now Punjab. Regional parties are a bigger threat to the Congress than the BJP”, he added.

Congress spokesperson Akhilesh Pratap Singh said that communalism is outweighing other election issues, and that the party has worked very hard to present a strong opposition.

“We only talk about development, policies, citizens’ issues, but the BJP only communalises elections and politics. Religious frenzy and casteism are outweighing real issues,” he added.

Singh also said that the party is now brainstorming a fresh strategy, adding, “We will try to make the voters aware again that they have to rise above communalism.”

In an interview with India Today TV last week, political strategist Prashant Kishor said: “The Congress party needs to fundamentally change the way they organise themselves, the way they conduct themselves, the way they lead their mass outreach, it needs a lot of changes in order to revive. You cannot cure cancer with some antibiotic, right?

“If the Congress wants to revive itself, it has to take a long-term approach, at least 7-10 years,” he added, pointing out that the party had been in “secular decline” since 1985.

Methodological note: We have factored in only those constituencies where the Congress contested and lost. There are also constituencies where the party did not contest and may or may not have won in the past. These remain outside our analysis.

In 2009, the delimitation exercise changed the names of Lok Sabha constituencies. Some were merged and some ceased to exist. These old constituencies were mapped based on their assembly segments. The names of the present-day Lok Sabha constituencies that contain most of the assembly segments of the old ones were then used to make the analysis comparable.

(Edited by Rohan Manoj)

Also read: Electoral bonds put over Rs 1,200 cr into parties’ kitties this poll season, govt data reveals