Early in the nineteenth century, a half-Tamil Malay employed by the East India Company’s intelligence service completed his Hikayat, a rare non-English memoir of his visit to “a country to the north, inclined towards the rising sun, a country of great size.”

Ahmad Rijaluddin’s Hikayat describes a globalised world, relatively unfettered by passports, visas, trade quotas and industrial policies. The state—if the East India Company can be called one—concerned itself mainly with providing security for its primary purpose, which historian Nick Robbins remind us was the relentless pursuit of wealth.

Few would recognise that cosmopolitan hub of manufacturing, international trade luxury and city today as Kolkata. Ten years ago, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the much-hyped Act East Policy, many experts hoped the move would transform India’s eastern seaboard, and restore its historic ties with East Asia. The anniversary, scholars Yannitha Louis and Jaideep Singh observe, has however passed almost unnoticed in both India and its neighbourhood.

Earlier this year, a survey by the prestigious ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, showed India was seen by South East Asia residents as “the least strategically relevant partner to the ASEAN member nations.” It ranked ninth among the 11 dialogue partners of the ASEAN nations on regional influence and leadership. Respondents from Myanmar and Singapore ranked India as fifth and sixth respectively in terms of strategic relevance.

The failure can be attributed to geopolitics and the inertia of government institutions—but it is also one of the mind.

From across the world, adventurers, mercenaries, entrepreneurs, manufacturers gathered under the shade of the great multinational Calcutta of the 1800s—creating a genuine melting-pot that rivalled the globalised mega-cities of our own time.

Also read: The spy who sold out Subhas Chandra Bose—he worked with Britain, Germany, USSR, Japan, Italy

Encountering Kolkata

Little is known about the author of the Hikayat: The manuscript in the collection of the British Museum, the scholar of languages Cyril Skinner wrote, describes him as “a Malay who accompanied an English Gentleman to Bengal,” and “the Teacher of Mr. Robert Scott”. The son of Hakim Long Fakir Kandu, an ethnic Tamil chulia trader from the Coromandel coast, Rijaluddin grew up in Penang, leased to the East India Company by the Sultan of Kedah in 1786. The Hikayat was, almost without doubt, the first work of its kind by an Asian.

From the markings on the manuscript, Skinner suggests, it seems Rijaluddin travelled to Kolkata with William Scott, one of the sons of the magnate Robert Scott, the owner of Forbes & Scott.

Likely, he was recruited as a language teacher by the East India Company intelligence service set up by Thomas Raffles. Raffles served as administrator of Penang from 1805-1810, before going on to play a key role in the founding of Singapore.

“For centuries,” historian Sunil Amrith records in his luminous account of the eastern sea, “the Bay of Bengal was crossed by troops and traders, by slaves and workers. It was a maritime highway between India and China, navigable by mastery of its regularly reversing monsoon winds.” European powers arrived in the fifteenth century, bringing their maritime power to bear against Asian rivals, as well as each other.

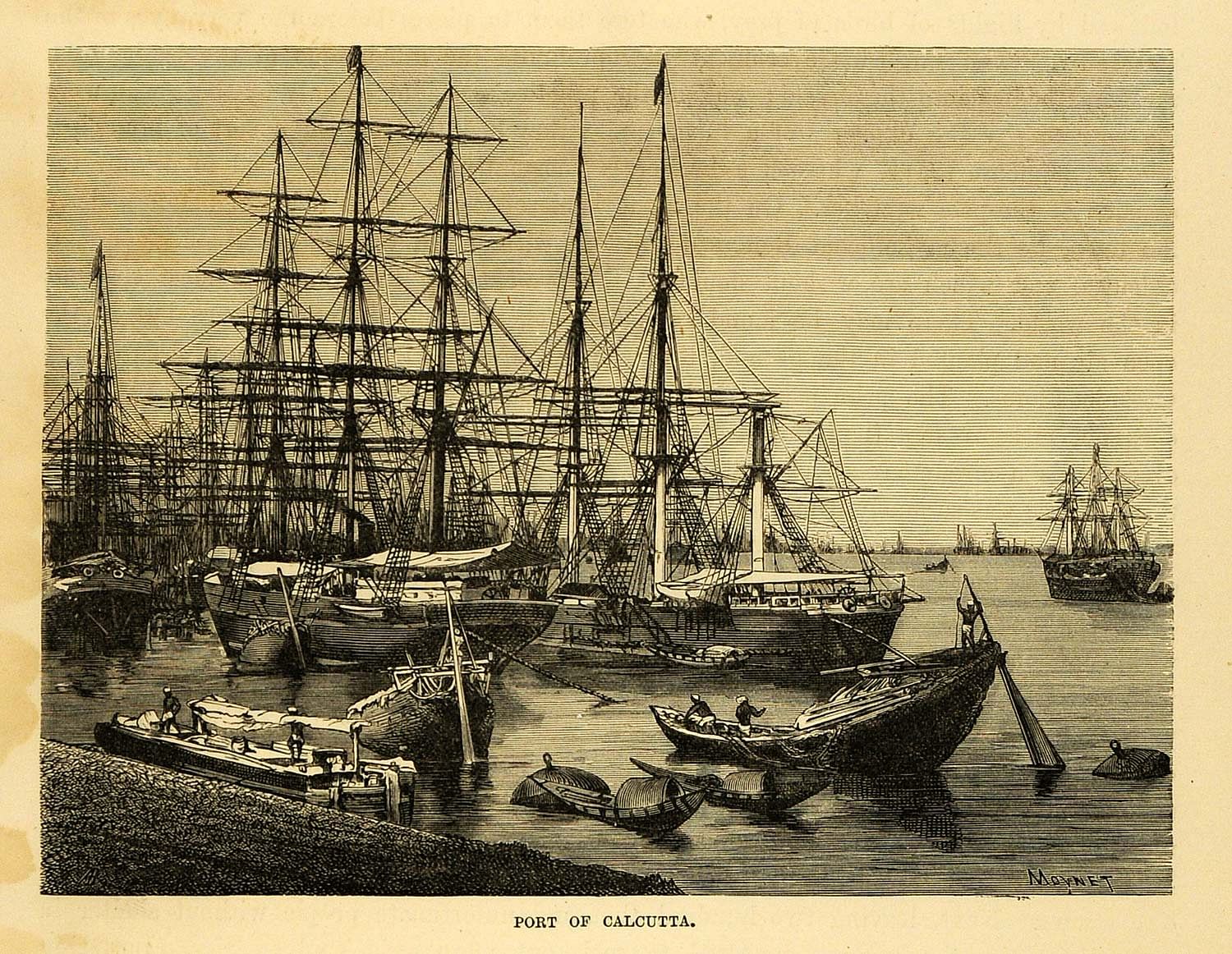

…ships visit the capital without a break, there is no let-up day or night; thousands of ships arrive and depart, and from the west to the east, from the north-west to the south-east, however many months the voyage takes, ships sail here to trade, ships too many to enumerate

– Ahmad Rijaluddin

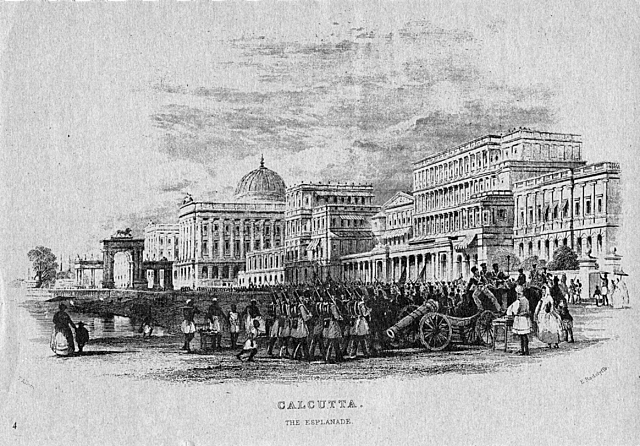

Encountering Kolkata for the first time, Rejaluddin reacted in language made familiar to us by modern New York travel memoirs. From the estuary, he saw “a city of immense size with a huge fort, several leagues long and several leagues wide, built in tiers several storeys high, as pretty as a picture…The river that encircles the fort is as deep as the ocean, and several ferocious crocodiles are kept in the moat, together with all manner of fish. The fort is immensely strong and looks as though it were made of highly polished wrought iron.”

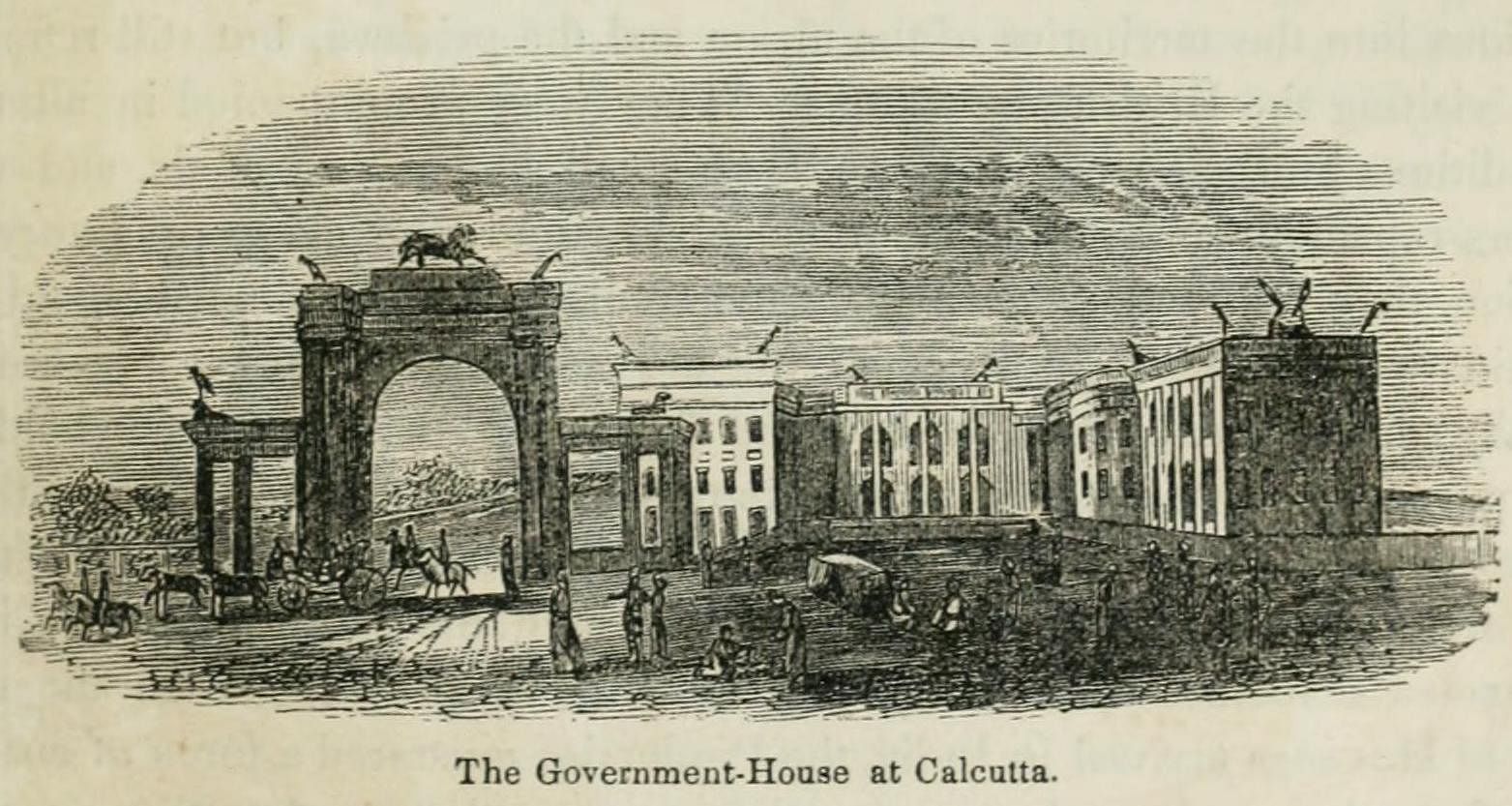

“Viewed from the sea, the fort looks like a savage tiger about to spring,” Rejaluddin wrote. English soldiers commanded an Indian army, made up of “Shaiks and Saids, then Moguls, Pathans and Hindus—Rajputs and Brahmans— in all, some hundreds of thousands, all of whom are on guard, patrolling day and night.”

Local notables, Rejaluddin went on, came each day to call on the East India Company’s viceroy, Gilbert Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound, “presenting him with all manner of fruit, while several watchmen and guards with swords drawn pace up and down like tigers, their eyes as big as hen’s eggs, their moustaches thick enough for birds to nest in. There are also any number of hookah-burdars, soontah-burdars, asa-burdars, bala-burdars and scores of chobdars, khansamas and kitmutgars.”

Also read: This is why Nehru-Liaquat Pact failed. Its ghost haunted Indian politics for decades

The moon and stars

“Like a moon surrounded by stars,” wrote Rejaluddin. Even if his prose was sometimes hyperbolic, Kolkata was indeed, in many senses, First City of the world. From Egypt, Constantinople, China, Mecca and every corner of Europe, Rejaluddin observed, “ships visit the capital without a break, there is no let-up day or night; thousands of ships arrive and depart, and from the west to the east, from the north-west to the south-east, however many months the voyage takes, ships sail here to trade, ships too many to enumerate.”

Little interest, Rejaluddin’s account suggests, was paid to the hinterland which supplied Kolkata: Early nineteenth-century mercantilism was not obsessed with territory. “The King of England sent tens, nay hundreds of ships, to investigate the source of the river,” Rejaluddin observed, “but none of them ever came back. That’s how it is with this river—there are too many jinns and sprites and supernatural creatures playing the devil’s own tricks and no human being has ever reached the source.”

To him, the important things were the markets: Kalpi, which sold chickens and ducks, as well as sugar-cane, bananas and citrus fruit in quantities that fed the crews of the ships; Kilikachi’s long lines of godowns housed the salt and arrack that the town produced. A league distant, there were Hindu artisans who produced cooking utensils, as well as locks, knives and axes. Chandni Chowk merchants offered gold, silver and precious stones.

“English and Indian merchants sell horses by the thousand, with carriages and various types of palkis,” Rejaluddin noted. The China Bazar, with its long mall-like building, specialised in imported gold thread, mirrors, silk, lamps and teapots. There were markets for red coral beads and for pearls.

The young traveller’s eyes, though, were drawn to the great dyeing works, turning out fabrics of “crimson, purple, aquamarine, green and yellow”: To the nineteenth-century trader, these textiles were gold. Long before Rejaluddin’s arrival in Kolkata, the physician François Bernier noted that “there is in Bengal, such a quantity of cotton and silks that the kingdom may be called the common storehouse for these two kinds of merchandise, not only for Hindustan or the Empire of the Great Mughal, only, but also for all of Europe.”

French traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, also in India in the seventeenth century, recorded that a “staggering 22,000 bales of silk, each weighing some 100 pounds [40 kilograms] was sold from Kaseembazaar, purchased by Mughal and Dutch buyers, as well as the English.” Kolkata also traded white calico, twisted cotton, and indigo.

Elaborate networks of Indian trade intermediaries, as well as financiers, linked producers to the trading hub in Kolkata, historian Shubra Chakrabarti writes, thus facilitating the flow of Indian-made textiles into global markets. The economic historian Om Prakash has shown that European trade created some 2,00,000 direct jobs, as well as some 8,00,000 indirect ones, helped improve the productivity of a largely rural population, and encouraged the monetisation of the economy.

Archaeologists have found evidence of a large South Indian merchant community in the Chinese city of Quanzhou, in the form of a Hindu temple dating from around the thirteenth century, containing hundreds of sculptures.

– Sunil Amrith, historian

This economy, Rejaluddin writes, was carefully defended by the East India Company. “The plain surrounding the encampment is a vast one and on it are several thousand wild elephants trained to wield iron chains and maces, and perform other feats,” he wrote. “There are also hundreds of thousands of thoroughbred horses of great size there, with many thousands of Indian warriors skilled in fighting on horseback, quick and fearless as an eagle pouncing on a heron, all fully armed with swords, shields, maces, stilettos, daggers, pistols, muskets and other weapons.”

“All the mahouts,” Rejaluddin went on, “wear coats of red broadcloth and on each elephant is a fearless Mughal or Pathan warrior, with a moustache like a buffalo’s horns, and eyes as big as hen’s eggs. They make a great impression on all who see them, like a tiger about to spring.”

The most important element of English power in the city, though, was a local police force, which ensured order. “In each street there is a bazar and each bazar has a police station with an inspector and several gendarmes always on a patrol,” Rejaluddin observed. These forces helped ensure the suppression of crime, and ensured unruly behaviour was rapidly put down.

A carnival-like atmosphere

Europe, historians teach us, did not invent this world. A millennium before the arrival of Portuguese, Dutch and English maritime power, historians Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany and Vijay Sakhuja have written, Tamil Nadu’s Cholas had ventured out from their bases in the Kaveri delta to raid South East Asia. This led to diplomatic engagement with China, then, as now, the preeminent power in Asia’s east. Tansen Sen’s superb work tells us that Chinese envoys, for their part, dealt with the rulers of Kochi and Kozhikode, and even ordered warlords in Bengal to cease their raids.

“Archaeologists,” Sunil Amrith reminds us, “have found evidence of a large South Indian merchant community in the Chinese city of Quanzhou, in the form of a Hindu temple dating from around the thirteenth century, containing hundreds of sculptures. In the Indian port of Nagapatnam, the ruins of a three-storeyed Chinese pagoda could be seen until their demolition in 1867.”

Tamil trade guilds, the eminent historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam records, secured themselves from Thailand to Java and beyond without invoking imperial power. Instead, they were careful to work with local authorities, alongside other communities of traders, like “Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong, Ryukyu islanders, Moluccans, traders from Java as well as mainland Southeast Asia, merchants from Sumatra, as well as participants in commercial networks linking Melaka to Pegu, Bengal, Coromandel, Sri Lanka, Kerala, Gujarat, the Maldives, and West Asia.”

From Rejaluddin’s account, it’s clear Europeans embedded themselves in this profoundly multicultural milieu. “The people watching are like swarms of flies,” he wrote of one festival, “so numerous that if you were to throw some sand up into the air when the entertainment was going on, not a grain of it could fall through to the ground. In the grandstand are English, French, Portuguese, Dutch, Danes, women as well as men, all enjoying themselves immensely, some singing, some dancing.”

“People of the different races—English, Portuguese, French, Dutch, Chinese, Bengalis, Burmese, Tamils and Malays—visit the place [brothels] morning, noon and night, and so it is always terribly crowded and as noisy as if they were celebrating the end of a war”, he observed.

Local police, he warns those tempted to visit, had the same ambiguous relationship with vice they are known for today. “Behind the police station great quantities of alcohol and hemp are sold and if anyone wants a drink, he goes there, to one of the booths.

“When the drinkers are half-seas-over they start to dance and sing and generally enjoy themselves, kicking up a fine old row, all you can hear is their shouting and bawling,” Rejaluddin writes. “They start to cry or dance or reel helplessly, while some are so drunk that they fall asleep, dead to the world. The man responsible for the sale of alcohol and hemp locks the door to stop them getting out and annoying other people in the area.”

“The officers of justice, the police and gendarmes arrive on the scene and lock them up in a building near the police station. The next morning the Police Inspector lets them out in case their masters kick up a fuss. This is how it goes on every day with never a dull moment.”

Entertainment in early-nineteenth-century Kolkata was, however, about far more than sex. Rejaluddin describes the city’s carnival-lime atmosphere with wonder: “There are conjurers who perform all sorts of baffling tricks; there are puppeteers with puppets representing human beings riding on horseback or on elephants or camels and various other sorts of puppets which, as a result of the sleight of hand practised by these Bengali Hindus, seem as though they can dance by themselves. There is also a woman who dances on a long bamboo pole: she balances on her belly in the middle of the pole and spins around at great speed, like a windmill.”

“There is also a fakir who has a tame goat, a monkey and two bears; he calls upon the goat to climb up on to a bit of wood no bigger than the lid of a small saucepan, telling it to put all four of its feet on the bit of wood”, Rejaluddin writes. “As for the monkey, the fakir has a rope with a noose and tells the monkey to jump into the noose, which it promptly does.”

Also read: Rabinder Singh spy scandal exposed R&AW’s ugly sides. But India hasn’t learned from its mistakes

The curse of power

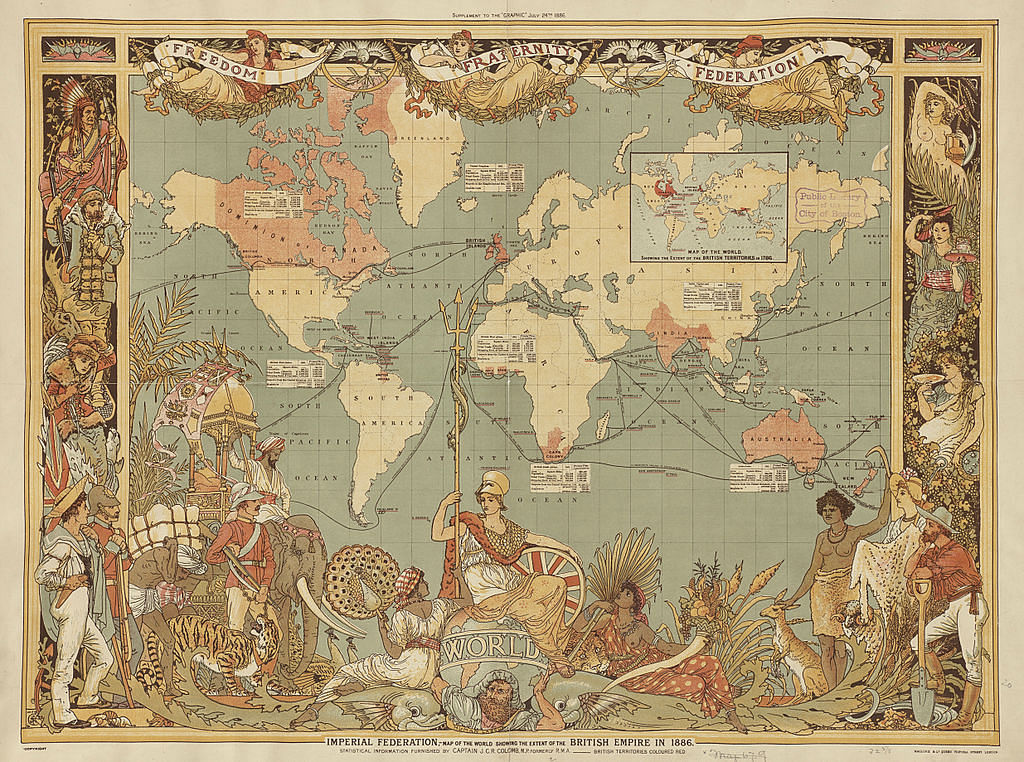

“England has no rival,”, Rejaluddin concluded. “It is like a fierce tiger which searches everywhere for an opponent but can find no one ready to take it on; because all are agreed on common policy, it prospers in all it undertakes.” The East India Company would, as Rejaluddin recounts, crush its competitors from Holland and France, capturing Mauritius almost without resistance in 1810, just as Rejaluddin arrived in Kolkata. The Dutch in Batavia had already been crushed in 1806.

Rejaluddin, with more attention to colour than fact, has Dutch Governor say: “Our European territory has been seized by the French king, called Musa Bonaparte, so we take up residence here in Java, hoping to live in peace. Now comes this threat from the English; where can we go now to seek refuge?”

Yet, Rejaluddin was right on one important thing: “Everybody was scared of the English who seemed like hungry tigers.”

There is reason to wonder, though, if English geopolitical primacy in the Indian Ocean was worth it. The East India Company did gain vast riches from India, but also found itself mired in a series of expensive—and, arguably, pointless—wars of territorial conquest. Following the rebellion of 1857, Britain’s parliament nationalised the company, taking over its army and its administrative infrastructure.

The Empire, Barbara Harlow and Mia Carter note in their collection of its internal debates, rested on the assumption that India was “hopelessly stuck in the static time of ancients or heathens”. “The Indian people were allegedly governed by superstition, ruled by hysteria and idolatry, and wholly without functioning economies and markets or life-sustaining communities and traditions.”

These were not, however, the beliefs of the free-market European pioneers who traversed the oceans to trade with Kolkata.

England’s draining of wealth from India, economist Pilar Nogues-Marco argues, led to the underdevelopment of its colony, ultimately degrading the value it could have gained had transnational trade networks been allowed to organically grow and flourish. Greed also destroyed the cosmopolitanism of Kolkata, replacing it with a race-bound hierarchical order. The death-blows to the Empire would be delivered by the killing of free trade by the Great Depression, and then the Second World War.

India’s Act East policy was intended to recreate the great networks that traversed the Bay of Bengal. The reality, however, is that it has floundered, for reasons Rejaluddin’s manuscript helps us comprehend. Kolkata in the early nineteenth century was a great manufacturing hub, which turned out cheap commodities the world wanted. And it was a city that welcomed diverse cultures and communities, embracing them without cultural judgment in a common project of shared prosperity. There were no boundaries of geopolitical affiliation, belief systems or borders.

This is the world India must imagine itself as, as it seeks to integrate with the economic powerhouses to its East. A globalised India involves not just some bureaucratic arrangements, but a project of imagination.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)