On 19 May, the offices of Congress were attacked in Srinagar and set on fire. The Congress obviously blamed the National Conference which predictably denied it, but in the process one thing was made abundantly clear—there were powerful enemies of the Congress in the Valley, and that the Government of India had lost much ground since the time in 1958 when the followers of Prime Minister Bakshi had worsted the followers of Sheikh Abdullah twice within a short span. One of the occasions then was the Republic Day which was celebrated with great fanfare by the masses.

But now things had changed with the Congress and Farooq Abdullah battling for survival. During the election campaign Farooq Abdullah was careful not to challenge explicitly the finality of the accession of the State but still making it clear that over the years Article 370 and the autonomy of the State had been greatly eroded, and that it needed to be restored. Indira Gandhi, on the other hand, publicly refrained from challenging the significance of Article 370 and yet could not help from championing the cause arising out of regional imbalances and emerging as the protector of the largely Hindu population of Jammu against the oppressive policies of the Valley leaders. ‘Thus in 1983 Indira Gandhi, who at the beginning had set out to conciliate Dr Farooq Abdullah and bring about an effective National Conference-Congress (I) collaboration…now found that the whole issue had been so polarized that she and Dr. Farooq Abdullah stood facing each other like boxers in the ring after the first round of what promised to be a long and bloody contest.’

It must be acknowledged that, apart from the political compulsions, as a matter of principle, Congress could not have been supporting a Bill that paved the way for the return of those State Subjects who had opted for Pakistani citizenship during these long decades while there were thousands of Hindu State Subjects who had been displaced from that part of the State which was forcibly occupied by Pakistan and were still without allotted lands. The insistence of the National Conference to pave the way for the former Muslim State Subjects without addressing the Hindu grievances gave a new twist to the relationship between the National Conference and the Congress and the National Conference and the Hindus. In addition to this, there was the suspicion in the minds of people of Jammu that it was a ploy to alter the demographic balance in Jammu region in favor of Muslims. The number of people who had migrated from Kashmir to the Pakistan occupied region was negligible and in contrast the number of those who had chosen to migrate from Jammu to Pakistan was substantial as was the number of those who had been forced to migrate from the Pakistan-occupied-Jammu region to the State. If all those, after so many years, chose to return then the demography and the consequent political equations too would change, thereby leaving the Hindus of Jammu at the mercy of Muslim communalists. Thus, overt communal polarization got injected in politics though, careful analysis will prove that it was always present because of the National Conference’s inability to take an unequivocal view of the subject. Many commentators tend to lay all the blame for communalism at the door of the Hindus of Jammu but the politics of vendetta unleashed by Sheikh Abdullah had pushed the humiliated Hindus into the lap of the only party that was willing to stand up for their rights.

To reverse this trend, tolerant, just and wise leadership was the need of the hour which, unfortunately, was not forthcoming from the National Conference. In such conditions prevarication on the part of the National Conference was to soon degenerate into a no holds barred fight. The Congress, on the other hand, was willy-nilly sucked into a situation that forced it to espouse a cause which, in the hands of a cunning adversary was easily painted as communal.

The poll results were startling as well as paradoxical. The two political parties—BJP and Jamaat-i-Islami—that identified itself as Hindu and Muslim parties respectively, were completely wiped out. The Hindus of Jammu and the Muslims of the Valley had rejected both. While the National Conference had won 46 seats (most of them from the Valley) out of the 75 Assembly seats, the Congress had bagged 26 seats, all of them from Jammu. In reality, it reflected the outcome of the proposed but aborted the plebiscite proposal of the Dixon Plan. Only three seats had been won by the Independents. While both the National Conference and the Congress professed their secular credentials, the struggle for power had transformed both to the extent that they came to represent the two faces of communal as well as regional polarization. Ironically, even in the face of this blatant communal picture, both insisted that they were secular at heart.

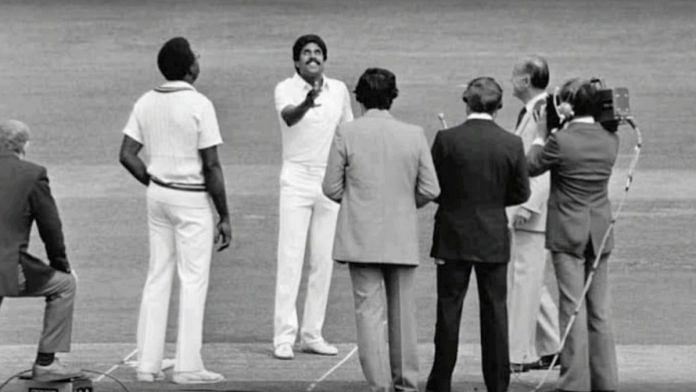

Another dimension, of equal concern, was the trend of increased violence and fraud. Violence, in fact had become widespread. Beginning with attacks on Congress workers and their deaths in police firing while demonstrating, violence had soon degenerated into selective and targeted killings. The symptoms had begun to emerge during the run up to the Assembly elections and boiled over in October 1983 during the one-day cricket match between India and West Indies in Srinagar. The Indian players were subjected to abuse and pelted with rubbish. The match was interrupted by protesters and rain before the visitors won after curtailment. Historian Alastair Lamb opines that the anti-Indian acts of the crowd represented powerful Muslim feelings feeding upon Muslim fundamentalism and, in his words, this clash of parties on a cricket pitch ‘can only be described as the first phase of a general Islamic rebellion against the Hindu domination of New Delhi.’

This conclusion, however, is challenged by another western historian, Sten Widmalm. He has pointed out that threats of violence and disruption of the North Zone Ranji Trophy cricket matches in Kashmir was present even 1978, but the situation then was different. Farooq Abdullah recalls in his book My Dismissal that, ‘I was the Chairman of [the] J&K Cricket Association at the time [1978], and with the backing of the State Government, we had to seek the intervention of the President of India, Shri Sanjiva Reddy, and the match was played without any incident.’ The reasons therefore have to be found in the circumstances that must have changed between 1978 and 1983. Probably the Cricket Board and the Government of India were too optimistic and believed that the love of cricket would make the Kashmiris forget politics. They therefore added Srinagar in the itinerary of the touring side. The fact though was that the State should have been warned of this, since the Centre must have gauged beforehand that bringing international cricket to Jammu and Kashmir would be a provocation to the Jamaat-e-Islami, which was critical of the accession of the State to India and had not accepted it in 1978, as well as in 1983. But before drawing a Lamb-like conclusion of India’s inadequacies, one must remember that in 1978 Sheikh Abdullah was at peace with New Delhi; Farooq Abdullah in 1983 was not, Had he been at peace, the troublemakers would not have created a hostile environment for the Indian team.

Extracted from A Modern History of Jammu and Kashmir, Volume Three: The Times of Turbulence (1975-2021) by Harbans Singh. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2024.

Extracted from A Modern History of Jammu and Kashmir, Volume Three: The Times of Turbulence (1975-2021) by Harbans Singh. Published by Speaking Tiger Books, 2024.