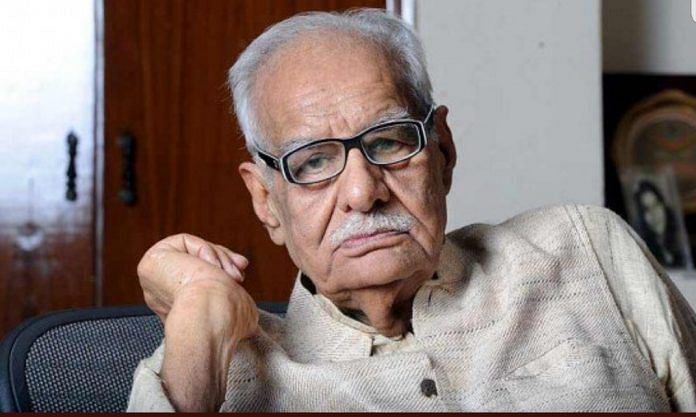

In his autobiography ‘Beyond the Lines’, veteran journalist Kuldip Nayar had expressed regret about the commercialisation of journalism.

Journalism as a profession has changed a great deal from what it was in our times. I feel an acute sense of disappointment, not only because it has deteriorated in quality and direction but also because I do not see journalists attempting to revive the values once practiced.

The proliferation of newspapers and television channels has affected the quality of content, particularly reporting. Too many individuals are competing for the same space. What appalls me most is that editorial primacy has been sacrificed at the altar of commercialism and vested interests.

It hurts to see many journalists bending backwards to remain, handmaidens of the proprietors, on the one hand, and of the establishment, on the other. This is so different from what we were used to.

At that time, proprietors left us alone to get on with the job of reporting, commenting on current political developments, and the like. I concede that there was a Lakshman Rekha which stopped us from transgressing beyond certain norms of free expression. It was, however, understood that journalists would not slant their story in a particular direction, nor make personal attacks on any leader in the government or political party. Also, the question of ‘paid news’ just didn’t arise.

Today the bulk of our newspapers and television channels are owned and run as family enterprises. The proprietors are usually the real editors, even when they have a front man called ‘editor’.

Also read: The India-Pakistan border haunted journalist Kuldip Nayar all his life after Partition

A few newspapers have members of their family formally trained. The Hindu took pride in this but N. Ram, the editor-in-chief, has stopped that practice which the newspaper adhered to for 140 years. He has appointed a professional editor and also a CEO, probably to underline that journalism is an industry, not a profession.

Shamlal once told me that as the editor of The Times of India, he was never rung up by Shanti Prasad Jain, the then owner of the newspaper, and that the latter did not even remotely suggest to him which line he should adopt on any particular subject.

Throughout Shamlal’s long tenure, Shanti Prasad never expressed his disapproval of anything the editor wrote. By contrast, the attitude of his son, Ashok Jain, who inherited Bennett Coleman & Co., publisher of The Times of India, was quite different. He was committed to commercial success and would ensure that the newspaper did not come into conflict with his business interests or those he promoted.

Giri Lal Jain, the then editor of The Times of India, rang me up one day to ask whether I could speak to Ashok Jain, whom I knew well, to get Samir Jain, his son, off his back. Giri said that Ashok Jain, whatever his preferences, treated him well but Samir’s attitude was humiliating. Inder Malhotra once recounted to me how senior journalists were made by Samir to sit on the floor in his room to write out the names of invitees on cards sent by the organisation.

I flew to Bombay and spoke to Ashok who frankly said he would have no hesitation in supporting his son because the latter had increased the revenue tenfold, from Rs 8 lakhs to Rs 80 lakhs. “I can hire many Giri Lal Jains if I pay more but not a Samir,” said Ashok. I conveyed this to Giri who did not last long with the newspaper.

The reason why The Statesman adopted an independent line even after the induction of C.R. Irani of the Swatantra Party as managing director was the influence of J.R.D. Tata. It is another matter that he caved in when the CPM took over in West Bengal.

N.J. Nanporia, the editor, would tell me that Irani was afraid to suggest anything to him because he knew that “I [Nanporia] can speak to JRD directly”. During the Emergency, Irani bought majority shares in The Statesman at book value because the owners were petrified and did not want to have anything to do with The Statesman or any other newspaper.

In The Indian Express, RNG (Ramnath Goenka) did not interfere until Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980. He would see the morning newspaper, which in those days was printed at midnight. Even if he noticed that a story was incorrect – he had wide contacts and knew what was happening in political circles – he would not stop its publication. He would tell me (I was the editor of the Express News Service) that such and such correspondent had got it all wrong; nothing beyond that.

Another instance of a proprietor’s whimsical attitude was the dismissal of Vinod Mehta from India Post owned by Vijaypat Singhania. Vinod was a very close friend. I was so worked up by his dismissal that I convened a public meeting at Constitution House and asked Vinod to come from Mumbai and address it. The hall was full. I was disappointed when he did not say a word against his proprietor, much less against the cult of proprietorship.

He read my thoughts and said, “You are mistaken if you thought I would say anything about proprietors. I have to look for another job.”

It is difficult to think of an ideal structure for the ownership of newspapers or television channels. I suggest that the leading ones should have an Ombudsman to ensure that they adhere to the policy enunciated by them. The Ombudsman should ensure that the employees are not shunted out by the proprietor, as Ram did in The Hindu to force N. Ravi and Malini Parthsarthy to resign.

Another suggestion is to separate the financial side from the editorial one. I mean the editor should have an annual allocation which he manages and the proprietor should not interfere so long as editor remains within the budget. Any additional financial demands should be worked out between the two.

In our days, the business or the advertisement department would maintain a distance from the editorial section because they were aware that we did not welcome even their managers. Whenever a press note or some other material came from them, we just threw it into the wastepaper basket. Even when they wrote B.M. (Business Must), it made no difference.

Today a new innovation called CEO has been introduced in newspapers as if the press was an industry or business house. The CEOs matter more than editors. Some newspapers, like The Times of India, have no editor. They proudly pronounce that the market is more important than the editorial content and are proud to sell news columns. That is how the term ‘paid news’ has come into currency, although the practice has been misused by regional papers beyond all limits.

Kuldip Nayar’s autobiography ‘Beyond the Lines’ was published in 2012 by Lotus, Roli Books.

Kuldip Nayar’s autobiography ‘Beyond the Lines’ was published in 2012 by Lotus, Roli Books.