Most of Bombay’s inhabitants opposed the measures against the plague. The privileged expressed their criticism in newspapers. Merchants were discontent with restrictions on mobility and the routine inspection and destruction of goods. Workers feared hospitalization due to the loss of income it entailed, instead preferring to leave the city—until millworkers and sweepers, the most essential yet least respected part of the workforce, were banned from doing so. Other parts of the population resented the fact that people of different castes and religion might mingle in hospitals. Women might have to be treated by male doctors, upper-caste Hindus might be served food prepared by impure hands—they might even be served beef. When violent protests against the plague measures unfolded, it was the hospitals that were hit first and quite literally so. People did not just throw stones at hospitals. They also attacked officials, some of whom died of their injuries. However, there were still worse places than hospitals.

Those who did not want to part from their infected relatives, servants or friends had to accompany them to plague camps. Each group arriving was given a tin hut with an open roof for better ventilation—and less privacy. At night, they would hear the sick in the hut next to theirs scream and kick against the walls in agony. Only 10 per cent of those stationed in the camps recovered from the plague. In the words of Lakshmibai Tilak, a contemporary writer, these camps were the kingdoms of the god of death.

Yet, this god was about to be fought by another one—a god in a white coat. As the plague raged on, Waldemar Haffkine, who had previously developed a cholera vaccine, developed an inoculation against the plague.

Haffkine bred bacteria with the help of what, to orthodox upper-caste Hindus and Parsis, was the purest of all substances—ghee. He took plague bacilli from the bumps of deceased plague victims, people of low repute and caste (the only ones available to scientists), and infused them in hot broth that contained small amounts of sterilized ghee. After maturing for some weeks, the solution was sterilized, decanted and stored in laboratory phials. This serum could be then injected in the bodies of just anyone—regardless of caste, social status and character. To be sure, inoculation was not mandatory, but the way the serum was produced and the risks it carried deeply appalled orthodox high-caste Hindus and Parsis. Not even the use of ghee, considered a purifying agent by many, could arrest their fears. It was not just that the serum seemingly polluted those inoculated with it. One could not even be sure that it really protected them from the disease or from death—or so the opponents of Haffkine’s serum claimed. Inoculation divided families and friends as some opted for it while others rejected it.

Mehtab was a fierce critic of inoculation, and so were her fellow members in the Bombay Theosophical Lodge, including some prominent British inhabitants of Bombay. Together, they imbibed any bit of information that discredited Haffkine’s serum—especially all cases of death seemingly resulting from it. While Mehtab’s sister patrolled the streets of the metropolis, encouraging people to get vaccinated, Mehtab and her fellow Theosophists likewise took to the streets to campaign against the vaccine, distributing leaflets in favour of nature cure and homeopathy to passers-by. ‘Cow Dung, Not Serum’, their leaflets proclaimed. This magic substance, after all, could be used not just as an incense in private homes, but could also be directly applied to plague bumps with the most surprising of effects. As Mehtab took her hat, bag and umbrella to leave for another day of proselytizing, she realized that her head was pounding, her heart was beating fast and she was in a cold sweat. Perhaps she had campaigned a little too much.

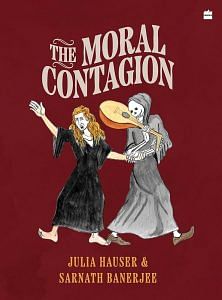

This excerpt from ‘The Moral Contagion’ by Julia Hauser and Sarnath Banerjee has been published with permission from HarperCollins.

This excerpt from ‘The Moral Contagion’ by Julia Hauser and Sarnath Banerjee has been published with permission from HarperCollins.