In this excerpt from Beauty of All My Days, Bond recalls seeing and hearing Nehru as well as his conversations with Morarji Desai, Acharya Kripalani.

I am sometimes asked why I never write about politics. Well, since everybody else does, I thought I might be the exception and concentrate instead on birth and death and the interval between.

The trouble with political issues is that they come and go very quickly, and if you make them a part of your story it is apt to date the writing. A short story I wrote sixty years ago, about meeting a blind girl on a train,* is still read with pleasure by young people today; but if the story had been about meeting a politician who was about to open an eye camp in his constituency, would it have the same impact today? The topical is for the day’s news media. The loves of Neela and Damayanthi, or Romeo and Juliet, or Laila and Majnu, are timeless storytelling.

But I have never ignored politics or political issues. After all, I have lived with them for over eighty years. I have lived through more governments and prime ministers than I care to count. In 1948, as a schoolboy, I received my literary and other academic prizes from the hands of Lord Mountbatten, still India’s governor general. Fifty-one years later I was receiving my first Padma Shri award from President K.R. Narayanan, and just four years ago I was honoured with the Padma Bhushan by President Pranab Mukherjee.

Different governments, different parties in power, different eras. I am fortunate to have witnessed a little history; political history, at that.

My first prime minister was Jawaharlal Nehru. I grew up during the Nehru years. He had no rivals.

Although a tolerant, widely read man, I don’t think he would have liked the idea of a rival. Although very English in some of his ways (and this accounted for his friendship with the Mountbattens) he was popular with the masses; he had the gift of being able to communicate readily with people from all walks of life. Children responded to him. He had received most of his education in England, and he thought and wrote in English. I had the privilege, many years ago, of reading his jail diaries (written during his imprisonment during the freedom movement), and in them he writes about the pleasures of reading poets such as Wordsworth and Walter de la Mare.

Nehru took his own writing seriously but without pretension. I wish some of our contemporary writers could be as humble. In 1959 I attended a talk he gave to a small audience in the Publications Division auditorium just off Janpath. He was in great good humour and spoke entertainingly about his London publishers. And like any professional writer, he talked about his royalties, about literary influences, about the pleasures of writing. Nehru understood the literary mind, the English mind. Unfortunately he did not understand the Chinese mind—who did?—and that led to the one disaster in an otherwise long and fruitful era of leadership.

It is not for me to go into the merits or demerits of subsequent leaders. Others are more qualified to do so.

I mention the Nehru years because I lived through them as a boy and as a struggling young writer, and those who did so are now dwindling in numbers.

People are surprised when I say that I saw (and heard) Nehru in his prime. That I met Morarji Desai (while I was working with CARE) and that he told me I should drink orange juice instead of alcohol (I’m afraid I did not take his advice). That I once shared a railway compartment with Acharya Kripalani and that he kept me awake all night with his criticisms of the Five-Year Plan.

Whatever happened to those Five-Year Plans? Whatever happened to Madhubala? Whatever happened to Krishan Chander, that fine writer?

Whatever happened to my Headmaster? Whatever happened to my best friend, Azhar? Whatever happened to Dhuki, who tended my grandmother’s garden?

History only tells us about the great ones who left their footprints on the sands of time. Dhuki spent most of his life growing sweet peas and petunias for an old lady.

That’s the kind of life I try to celebrate!

Another question that is sometimes put to me: ‘Haven’t you ever thought of living in another country—of settling down somewhere else?’

I think I saw enough of London when I was just out of my teens. The Thames, though a lovely river, is not as exciting as the Ganga.

China? Somehow I don’t see myself sitting on the Great Wall, writing Taoist fables. Someone might take me away.

As a boy I had romantic visions of Burma and the road to Mandalay. But it’s a harsh, intolerant land today. And I don’t see myself penning poems in a poppy field in Afghanistan; my intentions would be misunderstood. Further west, into Arabia and the Middle East, there is only death and disaster: Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya . . . When does the suffering end?

America? I’m no Hemingway, I’m afraid of guns. And he shot himself, didn’t he?

South America, up the Amazon? But they’ve cut all the forests away. W.H. Hudson’s ‘Green Mansions’ are now just a book.

Where else could I live and write? The choice in today’s world is rather limited.

Destiny, or the Great Librarian, brought me to this hilltop; Mother Hill near Mother Ganga, and here I have spent my best days and done my best work. And here I stay, until I have written my last word.

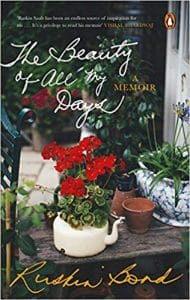

This excerpt is from the book ‘The Beauty of All My Days: A Memoir’ written by Ruskin Bond. The book was published by Penguin Viking in 2018.

This excerpt is from the book ‘The Beauty of All My Days: A Memoir’ written by Ruskin Bond. The book was published by Penguin Viking in 2018.

Would have got a chance to view this adorable personality face-to-face!