From initial times, the posture and mood of most wedding photographs from around the world remained serious and sombre. They were generally devoid of the kind of passion, desire, and notions of romantic love that one may associate with most couples getting married today. Today, even if a particular marriage is not necessarily the result of romantic love and sustained courtship, the photographs meant to capture that occasion are expected to reflect some attributes of romance, desire, fantasy, and so on. Compared to contemporary wedding photography, the same genre of photographs from earlier periods indicates a completely different set of preoccupations.

Examples from the very beginning of wedding photography right up to the mid or late 1940s are generally devoid of any kind of lightness in emotional terms. The main feature that was banished from within the frame to achieve this generalised sense of sullenness was the smile. The kinesics frozen on the facial expressions as well as body positions of these period photographs almost exudes a sense of sadness or unhappiness, as if these were the fundamental attributes symbolised by what the wedding represents.

The attempt seems to have been to inject a sense of exaggerated seriousness to the wedding photograph, and by extension to how the event was to be remembered in the future. In these circumstances, it is hardly surprising that early wedding photos look the way they do. But interestingly, this structure of emotion seen in wedding photographs from around the world seem quite remarkably consistent across geographic, class, national, and cultural boundaries, as if very different cultural settings somehow took a decisively negative position with regard to the public expression of contentment or happiness, which a smile is often expected to convey.

But the smile was not necessarily an indication of happiness in Victorian cultural settings. As Hirsch (1981) notes, if a family wished to appear happy, they were expected to pose in front of their property. The property in the background of their portrait painting or photograph would indicate their success and status in the material world, and hence the ultimate source of happiness. The smile, if it were present in a wedding photograph, would have completely changed its mood, which somehow was kept under control well into the 1940s.

Also read: Photography for all: The Hot Shot camera changed the way Indians clicked

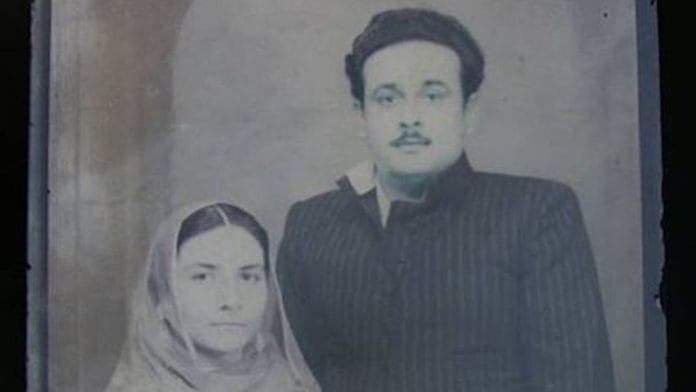

As a young man, I often wondered what was making my grandparents look so unhappy in their wedding photograph, taken in the 1920s. But even so, compared to other period photographs of the same genre, it appears that my grandmother somehow surreptitiously allowed the vestiges of a reluctant smile to enter the frame—without showing her teeth—while my grandfather adhered to the period norm of being solemn. So how and why was the smile so self-consciously expelled from this scheme of things?

The absence of the smile and the emotions it introduces were not restricted to wedding photography alone. It was something generally seen in photography across genres at the time, which was also adopted by wedding photographs as necessary decorum because it made sense, given the way the marriage itself was understood. Kotchemidova refers to this as the ‘invariably serious facial expression of nineteenth-century photos’. The smile in this specific context reflected a broader social concern or taboo, and to understand why the smile did not adorn wedding photographs, one must also understand why it was similarly not a part of any other kind of photography that involved a close study of human facial expressions. Fabry notes that it was only by the 1920s and 1930s that the smile came to be considered a ‘standard expression’ in photographs in general (Fabry 2016). But in practical terms, it was more clearly visible only after the 1940s, after World War II had ended.

Angus Trumble, in his book, A Brief History of the Smile, suggests that bad dental conditions partly explain why the smile was not seen in nineteenth-century photographs. He traces the development of dental health as an important criterion that allowed for the later emergence of the smile in photographs (ibid.). As he notes,‘people had lousy teeth, if they had teeth at all, which militated against opening your mouth in social settings’ (ibid.). But this does not mean that people did not smile at this time. And it is also likely that if bad teeth were the norm, being seen with such teeth in most social settings would also have been routinised and normalised. As such, this factor alone does not fully explain the nineteenth and early twentieth century’s frown upon capturing a smile in a photograph.

The inadequacy of technology is also used to explain why the smile is not visible in nineteenth-century photographs. That is, in the initial period of photography, it was necessary to hold a specific pose for a considerable period of time for the camera to capture it, given the longer exposure time in the early cameras (Fabry 2016). It was not easy to hold a smile for too long. As such, it would be natural to adopt easier poses. Even so, by the 1850s and 1860s, in the right conditions, it was quite possible to capture a photograph in a few seconds, and in the decades immediately afterwards, exposure times were made even shorter (ibid.). It is clear that the technology was available much earlier than we generally assume to capture a fleeting expression like a smile—if it was considered worth capturing. Seen in this sense, more than a matter of problematic dental hygiene and lack of the necessary technology, the issue seems to be the smile itself, or the norms governing public smiling and what it means in terms of etiquette.

Also read: Remembering Homai Vyarawalla, self-taught firebrand photographer who made her own rules

With reference to Fred Schroeder’s 1998 essay, ‘Say Cheese! The Revolution in the Aesthetics of Smiles’, Kotchemidova offers a cultural explanation that goes beyond the concerns of dental hygiene and technology in explaining the absence of the smile in early photographs. She notes that the standard expression in early group photos and portraits emulated the established practices of European portraiture, which generally tended to depict solemn faces, ‘occasionally softened by a Mona Lisa curve of the lips’ (ibid.: 2). So the smile was not a norm when the self and his significant others were captured for posterity in paintings or early photographs. Instead, it was an occasional or even an accidental occurrence. This is because ‘in the fine arts a grin was only characteristic of peasants, drunkards, children, and halfwits, suggesting low class or some other deficiency’ (ibid.). Within these conventions, the smile was clearly a sign of low social status or a matter of being uncouth. And such a feature was obviously not worthy of posterity.

In the transmission of the conventions of portrait painting to photography, this class-based sense of solemnity in the construction of a person’s likeness was blindly simulated. These conventions, meant initially for portrait painting, were considered the ideal form of behaviour when a person faced the camera. Further, general beauty standards in the late nineteenth century privileged a small mouth, which would also be challenged if a smile were to invade this sombre cultural repertoire (ibid.). As such, it was no surprise that the first photographic studio established in London in 1841 adopted the ‘locution “say prunes” to help sitters form a small mouth’, devoid of a smile (ibid.).

To some extent, this overall mood and the absence of the smile also comes from the way the marriage as an institution, and the wedding as the societal vehicle that initiates the institutional principles the marriage incorporates, were conventionally understood. Adshade and Kaiser note that, ‘the formalization of family structure through marriage creates a key economic and social institution for distributing resources and for the production of consumption goods as well as children’. In this scheme of things, the marriage formally brought men and women together ‘in genetic reproduction and household production’ (ibid.: 2). As suggested by Rose, the ‘home’, which is created by a socially sanctioned union, ‘was to be transformed into a purified, cleansed, moralized domestic space. It was to undertake the moral training of its children’. In addition, it was expected to ‘domesticate and familiarize the dangerous passions of adults, tearing them away from public vice, the gin palace and the gambling hall, imposing a duty of responsibility to each other, to home, and to children, and a wish to better their own condition’ (ibid.).

Seen in the sense outlined above, the smile in wedding photographs that we take for granted today, as well as in photography more generally, is a norm rooted in our time rather than in the first ninety years of photography’s history. That is why in contemporary times, most people naturally presume the smile to be a generic ingredient in such photographs, without reference to time.

This excerpt from The Fear of the Visual? by Sasanka Perera has been published with permission from Orient BlackSwan.

This excerpt from The Fear of the Visual? by Sasanka Perera has been published with permission from Orient BlackSwan.