Zardari’s presidency was never short of incident. He had to cope with an assertive military, street protests, judicial activism and a Taliban insurgency.

A politician who only won power because his wife had been murdered, he managed to do something no Pakistani leader before him had accomplished – handing over power to another civilian after a full term. That said, the election result at the end of his term was a rout: the PPP was all but wiped out in Punjab and pinned back to its heartland in rural Sindh. In 2008 the PPP had won 119 seats. In 2013 it won just thirty-three, leading some to wonder if the party would henceforth be little more than a regional outfit representing the Sindhi rural interest.

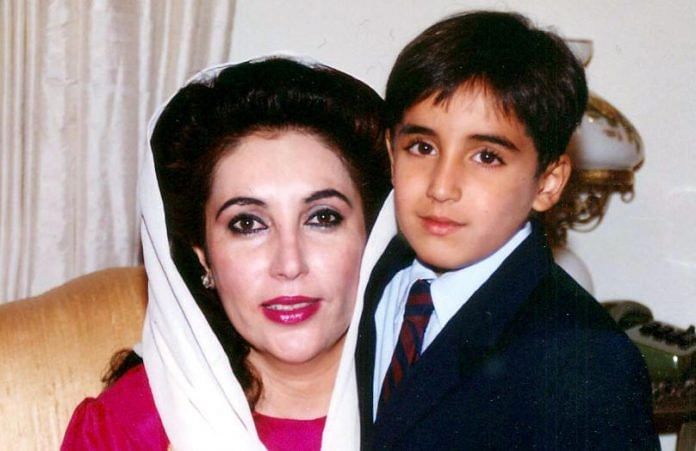

Zardari’s presidency had significant consequences for the PPP. In terms of its vote share, the party he left for his son, Bilawal, was considerably weaker than the one he inherited. He had also opened up internal fissures. As far back as Benazir’s first term in the late 1980s, senior PPP figures had worried that they needed to make a choice: were they with Asif or Benazir? In keeping with his Sindhi background, Zardari was not one to let bygones be bygones, and those who had aligned with Benazir found themselves pushed out when he became president. The most striking case was that of Naheed Khan and her husband Safdar Abbasi. Having met Benazir way back in her Barbican days in the mid-1980s, they had proved to be among her most loyal and hard-working associates, with Naheed Khan bearing the load of internal PPP management. Both had been with her in the car in Rawalpindi on the day she died. But Zardari never called on their services and replaced them with his own relatives and friends. As he tightened his grip on the party, PPP propaganda posters slowly but surely reflected the changing power dynamics: as images of Zardari’s face got ever bigger, those of Benazir’s shrank.

Also read: Bilawal Bhutto is the opposition’s dark horse in Imran Khan’s Naya Pakistan

WikiLeaked documents from 2008 and 2009 revealed how Zardari tried to shift control of the PPP to his own relatives. Benazir had opened the door for this by, for example, giving a National Assembly seat to Zardari’s father, Hakim Ali. But she had drawn lines. When Zardari asked for National Assembly seats for relatives, she sometimes turned him down. But now, with Benazir no longer restraining him, Zardari focused his efforts on his politically inexperienced sister Faryal Talpur, who was given Benazir’s old National Assembly seat in Larkana and made guardian to the three children. In February 2009 Zardari told US officials that in the event of his death he had instructed Bilawal to name Faryal Talpur as president. It is unclear exactly what he meant by this – according to the constitution the presidency would pass automatically to the chairman of the senate. He may have been talking about who would take over the running of the PPP. If so, it is unlikely that the party would have accepted her, but, in any event, it was clear that Zardari was thinking in terms of his own dynasty rather than a Bhutto one. There was one other hint that Bilawal’s status as successor was not an entirely settled matter. Hakim Ali had been the head of the Zardari tribe, and after his death in 2010 the question of who would succeed him in that role arose. In the normal course of events that title should have gone to his eldest son, Asif. But in May 2014, in a break with tradition, it was announced that Bilawal would get the job, presumably to tie him in to the Zardari side of the family. For some reason, however, that never happened, and in December 2014 Asif Zardari himself took the title, with a newspaper report saying somewhat enigmatically that ‘elders of his tribe advised him to refrain from handing over the position to Bilawal’.

These attempts to promote Zardari family interests were possible in part because, following Benazir’s death, there was no Bhutto in place to defend the family’s interests. While Bilawal was studying in Oxford, Nusrat Bhutto was suffering from Alzheimer’s and remained housebound in Dubai until her death in 2011. And while Mumtaz did churn out vitriolic newspaper articles denouncing Zardari, he was widely regarded as a spent force. Despite being aware that many in the PPP continued to distrust his father, Bilawal remained loyal to him. In 2013 he wrote an assessment of his father’s term in office, in which he said that Zardari’s legacy would be written in golden letters and that he would go down as one the most successful leaders Pakistan had ever seen: he had lasted a full term, held an election and handed over power to another civilian politician, despite having had to deal with sustained jihadist violence, a hostile Supreme Court, a power-hungry army and a parliament in which he did not have an overall majority. More than that, he surrendered key presidential powers and imposed a moratorium on the death penalty. Bilawal did not mention that the president’s reputation remained tarnished, governance continued to be poor, tax was still uncollected, the rule of law was still a distant aspiration and, by the time Zardari left the presidency, the country had so many power cuts that the opposition’s promise of ending them was a significant factor in the PPP’s election defeat.

Once he was out of power, Zardari was again unable to protect himself from legal cases brought by his opponents, and would once again find himself behind bars. Whatever ambitions Zardari may have harboured for his family, as his presidency receded into history it became clear that the PPP remained a Bhutto possession. That was in part because Bilawal left no doubt that he was committed to seeking power. That had not always been clear. Asked about his plans in 2004, he said: ‘I don’t know. I would like to help the people of Pakistan, so I will decide when I finish my studies. I can either enter politics or can enter another career that would benefit the people.’ The death of his mother put an end to any such options: as soon as he was named co-chairman of the party by his father after the burial of his mother, Bilawal realised that the PPP and its vast number of dependants, from ministers to lowly activists, needed him to keep the party in business. The pressure for him to go into politics proved irresistible. By 2018 Zardari’s health was visibly deteriorating and Bilawal was holding rallies up and down the country, proclaiming liberal values and attracting significant crowds, giving the PPP hope that it did have a future. As Bilawal looks ahead, he knows his first task is to secure control of the PPP itself. That has proved harder than many in the party hoped: Zardari is such a domineering character that it has been difficult for Bilawal to avoid being overshadowed. Bilawal does have the support of his sisters, Bakhtawar and Aseefa, both of whom have undertaken limited amounts of social work, particularly, in Aseefa’s case, concerning polio eradication. In 2019 she told the BBC: ‘My brother speaks for the entire Pakistan, and we will therefore continue to speak up and stand by our chairman, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari.’

Also read: Pakistan’s long-ailing democracy is now completely dead, thanks to its political parties

If he tightens his grip on the party, he next faces the task of winning over the voters. The problem he faces is not just that Zardari left the party electorally weak; there are broader trends at play. South Asia’s dynastic parties look increasingly outmoded. The paternalism and elitism implicit in dynastic politics do not chime in an era in which emerging middle-class voters with conservative, nationalist values are driving change. The failure of the Gandhis’ Congress Party in the face of Narendra Modi, the tea boy turned prime minister, would seem to hold bleak lessons for the Bhuttos’ PPP.

For all that, if the past is a guide then the most important factors in determining Bilawal’s future will be his relationships with the West and with the army. The prospect of continued instability in Afghanistan, the Pakistan military’s insatiable appetite for US aid, the worldwide concerns about nuclear security and the risk that the next violent jihadist attack on US soil could originate in Pakistan all suggest that Washington will remain deeply involved in Pakistani affairs. As Bilawal knows from his family history, finding an accommodation with the global power, as his great-grandfather Sir Shahnawaz and later his mother Benazir did, provides an easier path to power than opposing it. Even Zulfikar gave up on his anti-imperialist rhetoric of the 1960s, and, when he won power, came to appreciate that reassuring the US was more advantageous that criticising it. And Bilawal is well placed in this regard: his liberal outlook means he may well be able to persuade the next generation of American powerbrokers that he could be someone they could do business with. But even if he can make friends in high places in Washington, that still leaves the Pakistan Army. Whatever his private view of the matter, Zardari never accused General Musharraf of being responsible for his wife’s murder. Bilawal, however, has unambiguously blamed him, and he consequently finds himself in the same situation as his mother – simultaneously criticising a former army chief and reassuring the institution as a whole that he is not so hostile that they can never work together. It is certainly possible to imagine a scenario in which the army would need to install a civilian government with at least a modicum of legitimacy, meaning that it might turn to Bilawal as one of the few civilian politicians with genuine national visibility. The history of the Bhutto family suggests that, if that moment comes, Bilawal will probably make the necessary adjustments. He may give speeches demanding democracy, but his mother and grandfather did that too and yet found a way to work with GHQ. Indeed, ever since Doda Khan Bhutto worked out how to manipulate the British colonialists so as to secure the financial viability of his estates, the Bhuttos have always believed that, when the ultimate prize of power is at stake, a deal can be done.

This excerpt from The Bhutto Dynasty: The Struggle for Power in Pakistan by Owen Bennett-Jones has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from The Bhutto Dynasty: The Struggle for Power in Pakistan by Owen Bennett-Jones has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.