Indians have mixed meat with rice since as long as they have cultivated rice. Although it’s hard to see why other rice-eating civilizations wouldn’t have done the same, given the ubiquity of meat and the straightforwardness of the idea. But merely mixing rice with meat doesn’t a biryani make. It takes a series of very deliberate manoeuvres, improvised and fine-tuned over centuries. Long before biryani, came its humbler ancestor, pilaf. So that’s where the story has to begin.

Etymologically, pilaf is a later development. The word’s lineage goes all the way back to puṛukkal or puzhungal, Tamil for ‘cooked rice’.

This could have initially just referred to boiled rice, not necessarily with meat, as the name itself derives from puṛukku, which means to ‘boil paddy before husking’. Later, the Aryans borrowed it into Sanskrit as pulāka. Now things start sounding familiar. From Sanskrit pulāka to Persian pelâv to Turkish pilāf and Hindi pulāv was a pretty straightforward journey. Somewhere along the way, meat hopped on to the bandwagon, if not already part of the puṛukkal, and pulao assumed its current form.

Some authors have claimed a reference to the dish in the fifth century Yājñavalkya Smṛti. Others take it further back to the first millennium BCE with references to preparations resembling pulao in the Mahābhārata. Be that as it may, one can safely accept the Indian origins of pulao in its most primitive form.

Also read: Indians just can’t have enough of biryani — 2.28 orders placed every second on…

Interestingly, the dish did not remain confined to India for very long. Nearly a thousand years before the Yājñavalkya Smṛti, came Alexander the Great. The map those days looked very different from today. What’s now Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrg yzstan and Kazakhstan, was then Sogdiana. Together with Bactria, its better-recognized southern neighbour, Sogdiana made up the eastern fringes of the Achaemenid Empire. The two provinces were the wealthiest of all, and the reason was a bustling trade route that cut right through them. Historians call it the Silk Road. In fact, three of its biggest cities—Bukhara, Samarkand, and Khujand—sat right on this route and hosted enormous markets where merchants from lands as far as China, Venice, and India came together to exchange spices, horses, tea,

and stories. This sustained interaction also helped introduce travellers from distant lands to each other’s cuisines.

The early decades of the fourth century BCE saw the emergence of an ambitious Macedonian who dreamed of conquering not just the Achaemenid country but also whatever lay further east. And he even succeeded to a remarkable extent. By 329 BCE, Alexander’s army was in Sogdiana. When the Macedonian entered the capital Samarkand, then named Marakanda, he discovered many culinary novelties, among them a luxurious dish of rice and meat locally known as pilāf.

It’s likely the dish was a Sogdian variant of the pulāv brought to the bazaars by merchants and traders from India. Alexander must have thoroughly enjoyed the dish, for when he returned to Macedonia, he brought the recipe with him. That, one could say, was Europe’s first interface with pilāf. So thus far, we have a rice-and-meat dish that emerged in some prehistoric Dravidian culture and then spread to the rest of the subcontinent with the Aryans, to Central Asia with Indian traders, and to Europe with Alexander the

Great.

Unfortunately, the exact recipe Alexander carried home is lost to time. It sure was written down but is still awaiting discovery. The earliest written recipe wouldn’t come for at least another 1,300 years.

Abu Ali Sīnā or Ibn Sīnā, better known today as Avicenna thanks to European merchants who couldn’t pronounce his name correctly, was a Muslim polymath who lived and worked in Sogdiana towards the turn of the tenth century CE. Although this prolific writer authored more than 400 books on subjects ranging from medicine to astronomy and from poetry to geolog y, he’s arguably best known for putting to paper the first ever extant pilāf recipe. For this, he’s still celebrated in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan as the ‘father of modern pilāf

preparation’. But make no mistake, the dish itself is far, far older than this ‘father’.

Either with Ibn Sīnā or before him, but certainly long after Alexander, the preparation reached Persia. The region was under the Abbasid Caliphate at the time. And the Abbasids were voracious eaters. Abū Jaʿfar al-Manṣūr, the second caliph in the line-up, had made himself a new capital city and named it Baghdad. This was a time of great affluence, especially for the seat of the biggest Muslim government of its time. Thanks to this affluence, the city became a fertile ground for some of the best gourmet cuisines from around the world. Naturally, the residents indulged generously. And so did the rulers. In fact, al-Manṣūr himself is said to have died from overeating!

Also read: Meat bhooni, barkakhani—When Khansamas won over White memsaabs, Anglo-Indian food was born

The fifth caliph, Hārūn Ar-Rašīd, was so worried by this trend that he even hired a personal dietician to approve his menu. But the practice died with him, and the Abbasids returned to their gluttonous ways. His grandson, al-Wāthiq bi’llāh, who took the throne as the ninth

caliph, was commonly referred to by a very unflattering nickname, al-Akūl (lit. ‘the glutton’).

Such was the gastronomical ambience when the star of the Sogdian kitchen made its way into Baghdad. The Abbasid kitchen being the melting pot of world cuisine, pilāf felt right at home, right off the bat, and quickly became a delectable royal fare. The journey doesn’t end here, though. Earlier, the Umayyad Caliphate had already taken it to Western Europe as the Andalusian paella. Later, centuries of culinary evolution down the line, the dish would return home to India as pulāo.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, less than a decade after the fall of the Abbasids, emerged a new empire-builder from the heart of what once used to be Sogdiana. It was a semi-Mongol warlord with a titanic ambition of building a transcontinental empire. His name was Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad, better known as Bābur. With some minor initial hiccups, he eventually succeeded in seeding an empire of his own on the Indian subcontinent, thus establishing the Mughal dynasty. The name, of course, wasn’t his idea. It was an appellation that came with the Persians as a corruption of Mongol. Instead, early Mughals used the term Gurkani, a reference to his great-great-great grandfather Timūr Gurkānī or Tamerlane.

Bābur, although from less than opulent origins, was a lover of good food and good poetry—both of which would become the hallmark of Mughal life despite the extreme austerity adopted by some of his descendants. But the man could never develop a palate for India or its food. In fact, he didn’t even intend to build an empire in India. His original mission was just to conquer as much of the subcontinent as possible, rake in all the gold he’d heard about in legends, and then retire to Samarkand. For better or for worse, that never happened.

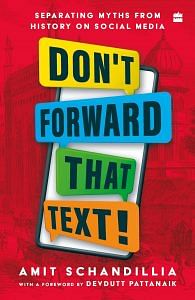

This excerpt from Amit Schandillia’s Don’t Forward That Text has been published with permission from Harper Collins.

This excerpt from Amit Schandillia’s Don’t Forward That Text has been published with permission from Harper Collins.