A Speedy Trial, an Execution and an Annexation Legend has it that a dervish in Ferozepur sent message to Shamsuddin: ‘Don’t go to Delhi; instead, go away to the hills.’ But when the summons came from Delhi for the nawab to cooperate with the British in the investigation of Fraser’s murder, the nawab chose to go to Delhi as he was sure he could not be implicated in the murder. But the British soon had a watertight case against him and within a matter of months, the case galloped towards its finale.

A hunt was launched forthwith for Fraser’s assassins. Suspicion fell on Shamsuddin literally from day one. His growing animosity towards Fraser was well-known and one Fateh Khan lost no time in telling Metcalfe that Shamsuddin could be involved. As luck would have it, a certain John Lawrence, a district officer then posted at Panipat, heard the news and immediately came to Delhi to offer his services to help Metcalfe and Simon Fraser, the magistrate, in the investigation. He employed two khojis, professional trackers, named Ram and Uda, to trace the culprit. He also knew of Wassail Khan’s connection with Shamsuddin and a search of the latter’s house revealed a horse with fine nail marks, indicating its shoes had recently been reversed and replaced. The horse’s minder was Karim Khan and a search of his quarters produced his correspondence with Shamsuddin. While being questioned, Karim Khan maintained his innocence and claimed he was simply visiting the city to purchase dogs for his master.

The evidence against Shamsuddin was still tenuous at best were it not for Ania Mewati. The countryside was rife with rumours that the nawab was plotting the murder of Ania to remove any trail that could come back to him. Apparently, Ania heard these rumours and, fearing for his life, first fled to the hills and then eventually gave himself up and turned King’s evidence.91 From then on, the events took a momentum of their own, in part aided by the outpouring of anger among the English in India and their fervent desire to make an example of the young nawab.

A desperate attempt on the life of Major Alves in Jaipur, the political agent of Rajputana, had earlier impressed upon the Governor-General the need to quell any stirrings of rebellion among the native chiefs. Shamsuddin was arrested and asked to explain his letters and the curious references to ‘dogs’, especially since Karim Khan had been in the city for several months and hadn’t bought any. Ania’s confession closed the loop, legally speaking. Moreover, Karim Khan’s sawn-off gun was accidentally retrieved from the well when a brass pot fell in it. Proceedings commenced against Karim Khan and Mirza Mughal Baig on 8 July 1835 with Judge Russell Colvin presiding. On 26 September 1835, Karim Khan was taken to the spot where Fraser had been killed and was executed. A large crowd gathered to watch the hanging and that day, prayers were offered in many of the city’s mosques for the man who had laid down his life for the cause of his master.

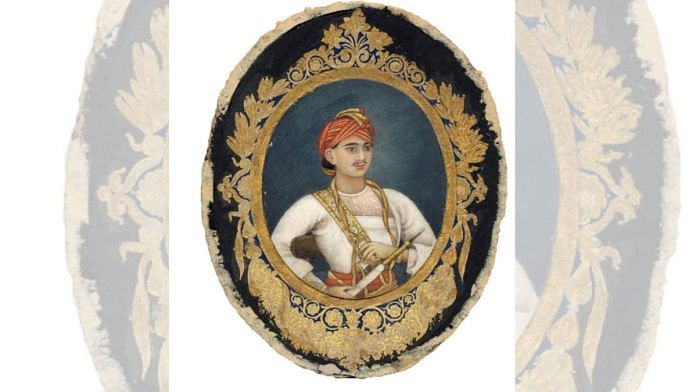

Finally, Shamsuddin was summoned for questioning in an open court. He arrived in a palki (palanquin) and was offered a chair to sit on, while several witnesses were produced to give their accounts of what they had seen. After hearing them, the judge gave his order – Shamsuddin was to be hanged. Ferozepur was annexed, all property which he had derived from the British government was confiscated and Loharu was left in the possession of Aminuddin, since clearly, he had no role in Fraser’s assassination.

Also read: Chola kings divided people into 2 caste groups—to pit them against each other and exploit

Ghalib re-enters our story at this point. He agreed to give testimony against Shamsuddin during the trial although this is in violation of the gentleman’s code of conduct since Shamsuddin’s father had long been Ghalib’s benefactor and the poet was tied to the young nawab by ties of kinship and family (Ghalib and Nawab Ahmad Bakhsh Khan traced their families to military men who came to India from Central Asia and Ghalib was married to Shamsuddin’s first cousin). The only reason for giving his testimony could have been Ghalib’s steadfast, relentless pragmatism as well as his tendency to watch out for his own interests while also looking out for the political cross-currents of the day. What is more, in his Persian diary entitled Dastambu, Ghalib calls himself a namak-khwar-esarkar-e-angrez (an ‘eater of the salt of the British government’ on account of his pension).

We have an eyewitness account of the mahaul (atmosphere) in the city, the rumour mills working overtime, the hushed sympathy for the ill-fated young nawab and the eventual execution, written by the traveller Thomas Bacon in his First Impressions. A warrant for the death of Shamsuddin arrived in the city on Thursday, 8 October. Rumours flew thick and fast of intrigues, surreptitious meetings, revenge and a group of ‘fifty native gentlemen’ vowing to free the victim from the gallows. Consequently, the most vigorous measures were taken for security, a double guard was stationed at the small cell where Shamsuddin was held in the cantonment, more troops were called in from Meerut and a body of Skinner’s Irregular Horse along with a large force of police and mounted soldiers from the neighbouring native chiefs formed an army, sufficient to defy the best-conceived schemes of the natives.

Bacon slept at Kashmiri Gate the night before in order to have a clear view of the execution. Here, on the fateful eve of the execution, he met Shamsuddin who had been brought to the gallows amidst great secrecy to avert any ploys to rescue him. Bacon and the nawab smoked a chillum (hookah) and chatted till the latter went to sleep. The next morning, Shamsuddin performed his wuzoo (ablutions)and offered prayers, spoke to Metcalfe about the disposal of his affairs and his family, dressed and combed his beard with great care, gave away his scarf, cummerbund and other personal articles to his servants, then left for the scaffold with utmost composure and dignity in a palki. Two thousand people had gathered to watch the spectacle; it was not a large number given his popularity, some stayed away for pragmatic reasons, others could not bear to see someone so young hang till death, especially as many were convinced of his innocence and a great many stayed away due to the excessive security cordons, Bacon surmises.

However, many high-ranking noblemen and chiefs did show up, dressed in all their pomp and regalia ‘as though they came to a gala’, to offer proof of their loyalty to the British and concurrence with the sentencing. Among those present were: the raja of Alwar, Maharaja Hindu Rao, the chiefs of Gwalior, Patiala, Nabur, Khittul and several other luminaries whom Bacon did not recognize and hence could not name. The nawab stepped out of the palki that had brought him to the site and with an air of ‘dignified indifference’ asked Metcalfe if he should ascend and, upon receiving assent, mounted the ladder with a firm step. ‘He died without a struggle; his slipper even did not fall from his feet,’ noted Bacon from his vantage position. While leaving the gallows, Bacon bumped into Hindu Rao who nonchalantly invited him to an evening of merrymaking at his home that evening: oyster pate freshly arrived from Calcutta and a nautch (dance) by the fabled Panna being the chief attractions. Bacon noted the uncouthness of the invitation but nevertheless accompanied Skinner to Hindu Rao’s soiree on the night of Shamsuddin’s execution.

Multiple Urdu accounts such as Qatl William Fraser by Nasiruddin Ahmad Khan (Khusro Mirza), describe the hanging of Shamsuddin Ahmad Khan outside the Kashmiri Gate in Delhi on 3 October 1835. The young nawab dressed in green clothes, befitting a martyr (whereas according to Bacon he was dressed in spotless white muslin), and the onlookers claimed that at the time of death, his body faced the qibla (direction of the Kaaba, the sacred shrine in Mecca), which became the subject of much local gossip for years to come.

According to Malik Ram, the Urdu critic and Ghalib scholar, Shamsuddin’s body was buried in Qadam Sharif. This is also attributed in the handwritten account by Nawab Aizuddin Ahmad Khan which says that Shamsuddin was buried at Qadam Sharif next to the grave of a brother of Mughal Baig Khan. Others hold that the young nawab was laid to rest in the graveyard at Qutub Sahib’s in Mehrauli where his father, too, was buried. Nawab Shamsuddin Ahmad Khan’s namaz-e janaza was offered by Maulana Shah Muhammad Ishaaq, grandson of the famous alim of Delhi, Hazrat Shah Abdul Aziz and it is said that 8,000 people attended this namaz-e-janaza. A great many in Delhi and Mewat were convinced that the British had acted in haste on slim evidence against the nawab. Others believed that the mercurial Fraser had received his just desserts. The latter view might well explain why, when the mutineers vented their ire against the British in 1857 and went on a rampage in the St James’ Church, Fraser’s tomb was so badly damaged that not a trace of it remained whereas the tombs of Skinner and Metcalfe remained unscathed.

A few days after Shamsuddin’s hanging, the case took a curious turn with Ania Mewati making yet another claim, this time by way of a petition addressed to the Governor-General in Calcutta. In it, he claimed that he had given his testimony as directed by James Skinner, Simon Fraser and others. In return, therefore, he now wanted the sum of `35,000, a monthly allowance of `100 and the grant of three villages in perpetuity, as promised by the above-named gentlemen. Much embarrassed, the government buried the letter.

Doubts, however, persisted about the fairness of the treatment that had been meted out to the late lamented Shamsuddin Ahmad Khan. Three years later, in 1838, in a meeting of the shareholders of the East India Company in London when the question of a vote of thanks to William Fraser and a sum of 5,000 pounds offered as compensation to Fraser’s brother and mother came up, one of the members present suggested that the sum should be offered only after the case had been reopened. Having seen some of the papers, this member believed there were substantial doubts; in fact, he went on to say that the papers indicated that Shamsuddin may well have been murdered. This was very much in keeping with the view among many in India that the sham trial and hanging was actually just a ploy by the government to possess Ferozepur Jhirka.

This excerpt from Rakhshanda Jalil’s ‘The Loharu Legacy’ was taken with permission from publisher Roli books.

This excerpt from Rakhshanda Jalil’s ‘The Loharu Legacy’ was taken with permission from publisher Roli books.