During the reign of Kulothunga Cholan I, the merchant clusters developed trade and commercial ties with countries such as Sri Lanka, Sumatra, Java, and Burma; they gained great wealth and influence. Meanwhile, war after war emptied the king’s treasury. The king refrained from imposing further taxes to avoid the merchant classes’ remonstrance. He used a trick to increase their income and earn himself money. The taxes levied on exported goods were lifted, which pleased the merchants. Their profits grew exponentially, and they even gifted a portion to the king. The king gained their support in this fashion. This information is found in Kulothungan’s inscriptions and Ottakoothar’s Kulothungan Ula (‘The Procession of Kulothungan’).

The Manadu inscription states thus: ‘A supremo who excluded taxes and reduced the burden.’

Similarly, Kulothungan Ula states: ‘Emperor Rajarajan waived the taxes during his reign.’

The occupational characteristics of individuals within the left-hand and right-hand clusters

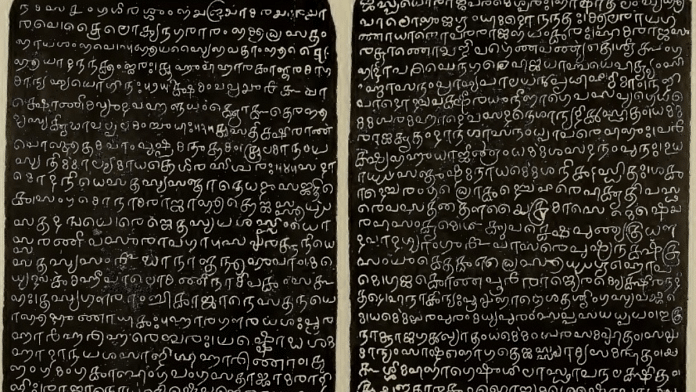

engendered disparities in their well-being. Both cultivators in the right-hand cluster and labourers in the left-hand cluster experienced commensurate hardship resulting from the exploitative land tenure policies imposed by the king. The king deliberately fomented dissent by exploiting and exposing age-old duels, preventing the groups from forming a united front against their oppressive rule. Historians state that these riots are addressed as left-hand versus righthand caste unrest, and such clashes blew out owing to convoluted perspectives about the superiority of one group as opposed to the other. One of the inscriptions from Aduthurai refers to the revolts between the lefthand and right-hand clusters. T.N. Subramanian refers to this through the following inscription:

Landowning communities, such as the Vanniyar, the Velaalar, and the Brahmins, united to cause injustices to the ninety-six castes in the left-hand cluster, helped by officials in the kingdom. Similarly, inscriptions excavated from several places in the State refer to the tax burden the left-hand castes bore.

Therefore, petty caste disputes were not the reasons for these continuous revolts but injustices meted out by the right-hand castes. While the king encouraged these injustices on the weak left-hand cluster, he offered them a few concessions when they grew strong

en masse.

The king and the landowning communities tried to create trivial fights within the left-hand cluster. When these attempts were successful, left-hand castes were vehemently subdued, and their taxes increased. Realizing the need for unity through experience, the left-hand cluster stayed united, as referred to in the Valikandapuram inscription. The inscription states:

In the inscription of Emperor of Swasthisree Thiribhuvanam, King Rajarajan, in the sixteenth year at Vadakarai Naattu Valikandapuram, in the Thiruvaliswaram Nayanar Temple that hosts all the left-hand groups, stipulates that everybody will share the good and bad fortune of the members: communities from various regions composed of Brahmins, Chitrameli Periya Naattaar, Yadava, Malayaman (chieftains), Kayangudi Brahmins, and Paravar. Through this inscription, ordinary folks have expressed their consideration to partake in the better and worse of each individual from their lefthand cluster and different castes referred to in it. Having promised to adhere to this pact, if anyone goes against it, he will be degraded lower than others and the lowly castes.

The latter part of the above inscription defines the fine imposed on those who violate this verdict.

This inscription advocates unity among the Idangai groups and encourages members of the Valangai groups, including Periya Naattaar, Yadava, Paravar, etc., to unite in solidarity against malevolent forces. It reflects the collective resolve of ordinary people, expressing the belief that any individual’s experiences, whether positive or negative, should be perceived and shared by all.

Most attempts by the kings to pit both caste groups against each other and prolong their exploitations were successful. After suffering many tribulations in public, the labour communities from the right-hand cluster promised to unite to resist evil and welcome goodness. The Valikandapuram inscription is historically significant and exposes the reality of caste practices.

These rare shreds of evidence make it safe to conclude that the riots between the left-hand and the right-hand groups were not mere caste riots but confederations of factions joined by landowning castes and the mercantile class, a clash due to class antagonism. We understand that the labour class of the lower strata from both clusters deliberately stood away and attempted to resist evil and welcome goodness.

This excerpt from ‘Caste Away’ by NA Vanamamalai has been published with permission from Hachette.

This excerpt from ‘Caste Away’ by NA Vanamamalai has been published with permission from Hachette.