T-shirts may be the most popular choice of attire at home or elsewhere, but it is way too mundane and irrelevant to be addressed or to qualify to be a part of an academic enquiry. T-shirts do not have the capacity to represent caste, class, or power as much as some of the traditional forms of apparel. No wonder why Indian scholars, even those who are working on contemporary visual and popular cultures, have never considered T-shirts as relevant texts.

T-shirt is a garment like no other, with enormous possibilities of textile variations. T-shirt’s ability to accommodate a whole range of texts and images implies the inherent hollowness of the commodity. It is otherwise so meaningless that anything can be imprinted on it. At the same time, the imprinted texts and images are not seriously representative of anything because of unceremonious nature of the garment where they appear. Images and texts on T-shirts derive their appeal from the very fact that they are casually imprinted.

What are the characteristics of its casualness? First, it is flexible and ambiguous. Second, it is minimalistic and has a mass appeal, as it rehashes the clichés of popular culture. Third, it is androgynous. Fourth, it is dispensable or it can be easily discarded. Fifth, and most importantly, it is symbolically empty.

A T-shirt can be bought anywhere, anytime, and anyhow without too much thought. It can also be disposed of without much regret—or the same product can be purchased yet again without much consideration. Most T-shirts can be bought whimsically, worn un-pressed, and thrown away as they fade with time and use. It is essentially hollow and empty, which is why it makes allowance for images or texts to inhabit its body so casually and ever so easily. The T-shirt does not have any emphatic social marker, which is why it can easily accommodate arbitrary visual or textual elements. This is also the reason why we do not mind wearing a T-shirt with random images or texts on it (unless it truly offends our sensibilities), whereas we may find it extremely inappropriate to wear a shirt or a sari with similar texts and images.

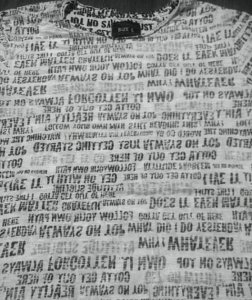

The T-shirt is an exception to the established correlation between the commodity and its signifying ability. It is an example of an aberration of the representational framework. It may convey informality, but nothing truly substantial. Unlike any other traditional clothing or formal dresses, which prepare one for certain professions, places, activities, or rituals, a T-shirt is inherently casual, even when it is loaded with texts and images. Only a t-shirt can possibly accommodate and entertain erratic spontaneity without any obligation of conveying anything cogent. It can even subvert the communicative abilities of the text imprinted on it, as seen on the T-shirt below.

Also read: Saying ‘Lal Salam’ now counts as sedition. Is Che Guevara T-shirt next?

Visual and Textual Imprints: New-Generation T-shirts

T-shirts became immensely popular in India after liberalization. Now, the digital era of app-based online shopping has witnessed the arrival of several online stores exclusively focused on selling this apparel. Consumers are tirelessly browsing Amazon, Myntra, Snapdeal, Flipkart, Jabong, Cloudstore, WYO, The Souled Store, Swag Shirts, and Bewakoof, to name a few. Texts and images on these T-shirts compete in order to outdo each other on their coolness quotient. There is a sudden rush of exciting content imprinted on T-shirts that should be studied as texts.

Even though T-shirts commodify people, places, time, events, and landmarks in a clichéd and caricatured manner, it will be erroneous to believe that the bearer necessarily subscribes to those textual or visual statements. T-shirt appropriates the role of a medium on which messages could easily be inscribed. It mixes wit, sarcasm, and urban vocabulary. The images and texts on T-shirts reflect upon the socio-political conditions in the post-liberalization era.

Addressing corruption and political disillusionment, one of the messages on a T-shirt claims: ‘Yeh bik gayi hai gormint’ (‘This government is sold out’—possibly to the corporates and neo-liberal policies). ‘Government’ is intentionally misspelled as ‘Gormint’ to add a touch of provincial phonetics. In another T-shirt with ‘Linkin Aadhar’ inscribed on it, the iconography mocks the much-debated compulsory linking of bank accounts with the unique identification number. The typography is suggestive of an anti-establishment leaning. It resonates the type- setting of popular rock band Linkin Park.

Two other T-shirts mock dietary and health regimes: One says, ‘Running late is my cardio’ and another stacks words as a piled-up filling in a thick burger to convey, ‘I fear that I am not eating to my potential’. Both use statements written in first person. Both ridicule obsessions with fitness and dietary prescriptions through the arrangement of text and graphics that are playful in nature.

Another T-shirt draws our attention to the copy-paste culture in the digital era by stating: ‘My technical skills: Ctrl C + Ctrl V’. It seems to claim that ‘copy-pasting’ is the only ability that one is left with, suggesting a lack of originality or widespread plagiarism.

Slogans like ‘So many girls, so little time’, ‘Why get married when I get it with no strings attached’, ‘My father is a mother fucker’, or ‘I know what you are thinking, let’s do it’ denote permissive sexual attitudes. But does it mean that someone who is wearing a T-shirt with such a message has to subscribe to those messages? ‘I was born intelligent but education ruined me’ is again an identifiable caricature but does not offer any indication of the level of intelligence of the person who is wearing it. Similarly, T-shirts carrying Buddhist thoughts neither impose an obligation on the wearer to follow them, nor make it imperative to make a pledge to serve the message.

Do you have to be a frivolous boyfriend in real life to wear a T-shirt that says ‘Freelance Boyfriend’? While ‘Aao Kabhi Haveli Par’ may sound like a mockery of a pick-up line, but does one wear it on the sleeves as a real pick-up prop? If you believe that love is eternal, does that disqualify you from wearing a T-shirt that says ‘Pyar China Ka Maal’? If the answer is ‘no’, then it is simply because neither the consumers take these messages seriously nor do the viewers feel attached to its implied meanings.

Also read: #JusticeForRhea,‘smashing patriarchy’– Bollywood and Twitter on Rhea Chakraborty’s arrest

Hybridization and Repetitiveness: A Dual Kitsch

To elaborate further, let us consider the specific case of the Buddha, who happens to be a popular T-shirt icon. Buddha, or any other figure for that matter, is devoid of any religious, mythological, and historical associations when seen on a T-shirt. Similarly, popular icons of Che Guevara, Bob Marley, Kurt Cobain, Gandhi, and Shiva on T-shirts are not necessarily signs of devotion. Anyone can wear them without being a devotee. One does not have to be a fan or a follower of footballer Cristiano Ronaldo to wear a T-shirt with his image on it. A Lionel Messi fan may choose not to wear a Ronaldo T-shirt, but all those who do wear it may not be Messi fans either. On a particular Gandhi T-shirt, we see an animated Gandhi uttering a message to relax: ‘Peace out bro’. The garment can also take the liberty of equating Gandhi’s long walk with Jonny Walker’s tag line—‘Keep walking’—without offending either. Similarly, one need not have an appetite for or intent of violence if one chooses to wear a T-shirt with a hyper-masculine and hyper-muscular Shiva, nor does one need to be a bhakt (devotee) to wear it.

Slogans or icons on T-shirts do not call for adherence to a particular philosophy in any form, but it is merely a consequence of certain individuals being iconized as saleable commodities. Individuals or trends become icons or messages only to be packaged as standardized signs of protest, resistance, peace, divinity, and so on. But at no point do these images and messages demand belief, practice, or even awareness, which is a proof of their facileness. Consuming a T-shirt does not entail the process of being consumed by it.

Unlike designer wear, which is purchased to make a class statement, the T-shirt is a mass-produced product meant for mass consumption, and often, a creation of low-cost urban infrastructures. It has no designated space in the wardrobe. It is not crafted to last for generations. It can be bought without much of a thought and discarded with lesser regret. It moves quickly towards its date of expiry, as soon as the icon on it starts fading. Like any other disposable, it is designed to be dumped soon.

T-shirt as a commodity captures the ephemeral tendencies of consumers to whimsically pick up ready-to-wear things and discard them soon too. The T-shirt icons is not eternal but ephemeral—till it lasts the wash.

Excerpt from Consumerist Encounters: Flirting with Things and Images (Oxford University Press, 2020)

nah, ur wrong