The other day my younger son rolled up a newspaper and hit our dog on his nose for being a little too frisky. ‘That’s how you do it,’ he said triumphantly, with the confidence that can only come from being a seven-year-old. ‘You don’t have to shout at someone to make them listen. This is what good parenting is about.’

The reference was clearly to me, his not-so-good parent. I am sure he won’t like it one bit if I start whacking him on his nose every time he does something annoying, but clearly he seems to prefer it to a screaming match. Being told off by one’s child is not a novel experience for a mother—certainly not for this mother. By the time your children enter adolescence, it is a great day if they deign to speak to you and an even greater day when they treat you like a human being.

The point is that everyone has a theory about how to be a mother, even those you have to mother, and in my case I am sure the dog has one as well.

Also read: ‘Tu jaanta nehin mera baap kaun hain’ and India’s anxiety about the father

You can be a tiger mom like Amy Chua and ensure your child grows up disciplined, which means no sleepovers, no play dates, no school plays, no complaining about not being in a school play, no TV and no computer games, no choosing their own extra-curricular activities, no grade less than A, no being less than the #1 student in every subject except gym and drama, and not having any option but to play the violin or piano. It also means going into battle with your child every day.

You can be a ‘cheetah mom’, which means you teach your children basic survival skills (in the case of actual cheetahs it is hunting prey and avoiding other predators) and then move on to creating a new family. I think this is pretty cool. You leave the siblings to take care of each other in sibling groups, which is surely the kind of collaborative qualities needed for twenty-first-century youngsters. If it sounds an awful lot like the French style of bringing up bebe, it is because it is. French mamans are only too happy to teach their children the basic rules and then quickly expect them to grow into adulthood as soigné and suave individuals, and they do. All they need is an occasional thwack with a Birkin bag. And— voila!—perfect little Macrons will emerge.

Or you can be a ‘helicopter mom’, which in India is now called a ‘WhatsApp mom’. So there you will be on WhatsApp obsessing about the colour of art paper to be used in the class project, or the half-mark missed because the teacher got careless or the role in the school play that went to another child. A WhatsApp mom exists to display to the world what a committed mother is really like, to monitor the child within an inch of a straitjacket and to show the school that it’s being watched.

You can also be a ‘drone mom’, which has been entertainingly but frighteningly described by psychologist Dr George Sachs as a ‘helicopter parent with silencers’. As he writes, helicopter parenting is over-parenting. Drone parenting takes this to a new level. It stymies the child’s development. A recent study by Brigham Young professors titled ‘Is Hovering Smothering or Loving? An Examination of Parental Warmth as a Moderator of Relations Between Helicopter Parenting and Emerging Adults’ finds that, regardless of your intention, continually dipping in and out of your child’s life to save the day is psychologically and relationally detrimental. No matter how much you say you believe in your child, your actions say otherwise. Soon, your children get the message. They don’t do conflict. They don’t do boundaries. They don’t do discomfort. They just don’t do much on their own.

If the poor mother isn’t already addled by all the choices of parental styles, she also has her mother’s advice, usually solicited, and her mother-in-law’s tips, usually unsolicited, to listen to. And if you manage to raise one child successfully, there is no guarantee the other will turn out the same.

Also read: No three-tiered wedding cake, no mangalsutra: Single women a growing tribe in India

Please note, by successful here I don’t mean the proverbial Sunder Pichai and Indra Nooyi level of success. I have more modest expectations. If a child is capable of earning a living, supporting a family at some point, of whatever gender persuasion, and is not a threat to society or himself, that is a job well done. World domination is for other mothers’ children, thank you very much. So even if one child turns out fairly regular, there is always the second skulking about, waiting to trip you up in your eternal maternal smugness. But as a wise professor at the Delhi School of Economics once told me, having one child is an experiment, two is what makes a family. He said nothing about what sort of family. More fool me, I should have asked.

In my case, the family is barely sane. The nicest thing anyone has ever said about my children was by an Australian friend who, after a particularly harrowing lunch where my older one was constantly underfoot, declared that my boy would make a great brand ambassador—for permanent birth control. This was only slightly less embarrassing than the time my son, at the age of four, turned up totally naked in the fountains of the Bikaner royal hunting lodge, and splashed about without a care in the world, as the Maharaja of Udaipur and the then-Union railways minister watched in shocked silence. The latter died subsequently, one hopes not as a result of seeing my son in all his naked splendour.

Fortunately, the other boy had not made his appearance into the world till then, so perhaps that is why he isn’t scarred for life. A friend who has watched them over the years has possibly the best description for them, describing them as Vijay and Ravi aka actors Amitabh Bachchan and Shashi Kapoor from Deewar. One, the angry young man and the other more reasonable. And I, the longsuffering Nirupa Roy.

Also read: Airtel to Amazon — how big brands get the idea of feminism terribly wrong

Which brings me to what I think is a valid demand. If our children get to tell us about other mothers—those who bake birthday cakes, help with homework, and cook fresh meals every day—why can’t mothers talk about other children? The ones who get 99.9 per cent in their Class XII exams? The ones who remember their mother’s birthday and their parents’ anniversary? The ones who are always happy to run an errand to buy bread or milk? The ones who make their own beds and clean their own rooms? The ones who basically do as they’re told, like human versions of Alexa. If ever there is a Maternal Bill of Rights, I know I’m starting a pressure group to get it passed.

Still, it isn’t as if mothers don’t get it right. Very often they do, managing a full career, a complete domestic life and an engaged public life. Smriti Irani, actor and politician, is one of them, and happens to be the daughter of a working woman as well. Irani is the eldest of three sisters and they were all raised to have a mind of their own. At 7.30 a.m. her mother would leave with the three girls as they walked to school and expect to have the house neat and clean by the time she returned in the evening. ‘It gave us a sense of freedom but also of responsibility. She made sure the books lying around were not romances but Nancy Drews and Hardy Boys. She didn’t want us to have a romantic view of life. But she supported our every adventure. And we three took care of each other’, recalls Irani.

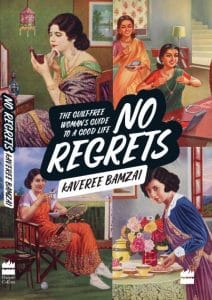

This excerpt from No Regrets: The Guiltfree Woman’s Guide To A Good Life by Kaveree Bamzai has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from No Regrets: The Guiltfree Woman’s Guide To A Good Life by Kaveree Bamzai has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.