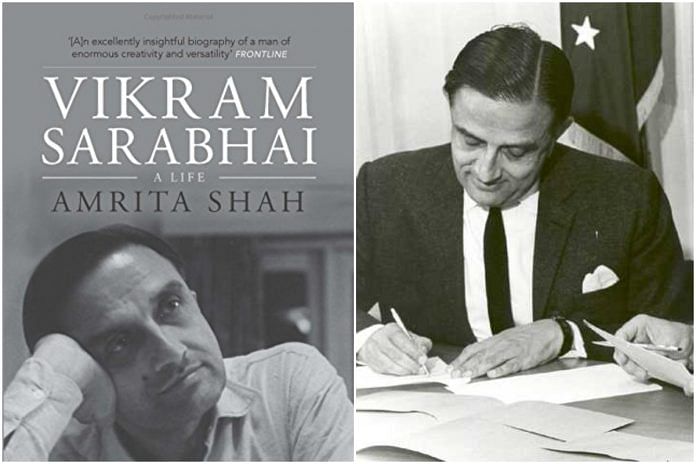

On the birth anniversary of Vikram Sarabhai, one of the minds behind India’s space programme, we take a look back at his life through his biography by Amrita Shah.

This day in 1971, one of the pioneers of India’s space programme, Dr. Vikram Sarabhai, bid goodbye to this mortal world. Convinced that an independent country struggling to get on its foot must have a comprehensive space programme aimed at benefiting the humankind. At the same time, India was also developing nuclear capabilities. But all was not well between then prime minister Indira Gandhi and the Atomic Energy Commission, a body under the Department of Atomic Energy, chairperson Vikram Sarabhai.

Read an edited excerpt from his biography ‘Vikram Sarabhai: A Life by Amrita Shah’.

Vikram enjoyed an undeniably strong rapport with Indira till the late 1960s. At the professional level it was evident in the consonance between their public utterances on certain issues. On 24 April 1968, in an echo of Vikram’s press conference, for instance, Indira said in the Lok Sabha: ‘We think that nuclear weapons are no substitute for military preparedness involving conventional weapons… [it] may well endanger our internal security by imposing a very heavy economic burden.’

Around this time, Vikram was taking Kalam and Narayanan to the distant airfield to discuss RATO systems for military aircraft. Following the meeting, Kalam reports, Vikram went to the prime minister’s house for breakfast. The same day, an announcement was released to the press about India developing the RATO, suggesting a prior discussion. Describing Vikram as ‘the most dynamic of the Sarabhai clan’, Raj Thapar said he was seen ‘frequently in Indira’s entourage, literally running behind her’.

By the end of the 1960s things had begun to change. Politically it was clear that Indira was winning the battle against the old guard in the party. With experience she had grown more confident and the overwhelming support of the electorate was to give her an even greater rootedness. But the machinations and power play had changed her and made her increasingly suspicious and intolerant of others. Raj Thapar vividly describes the transformation as one by which she alienated her old friends and advisers. P.C. Alexander, who was to be her principal secretary in the 1980s, observed that she ‘was one of the loneliness [sic] leaders in contemporary history… [I] always had the feeling that she never trusted any person completely or unreservedly’.

Raj Chengappa maintains that the seed of a schism between Indira and Vikram was laid in the late 1960s itself. According to him, senior scientists of the atomic energy fraternity, concerned about any bargain that the Sarabhai—Jha team might have struck with the superpowers, had maintained links with the prime minister and her advisers directly, cautioning them about the danger of giving up India’s nuclear options. Such an exchange, if it did take place, would have been of extremely questionable propriety. But the scientists at AEC, as shown time and again, considered themselves the keepers of India’s security. Vikram had failed completely in his effort to change that mindset and push nuclear defence policy where he felt it belonged, in the public arena.

On the other hand, it is conceivable that Indira, with her growing tendency to play people against each other, could have given a patient ear to the scientists’ anxieties. Perhaps the reservations she had expressed earlier about a weapons programme were never based on conviction. Her advisers too had changed. The moderate L.K. Jha had become governor of the Reserve Bank; his successor P.N. Haksar and G. Parthasarthy, Indira’s adviser on foreign policty matters, were markedly more hawkish in their views.

The issue that seemed to be exercising the anti-Vikram lobby, if disparate individuals with a common cause could be that, though was not a weapons programme—on which Vikram ‘s views were ambiguous—but the desirability of a demonstration. What the politicians, bureaucrats and senior scientists at the AEC wanted was a show of India’s might. And there was no question of Vikram’s stand on that. At the very outset Vikram had made his views on a demonstration clear, going so far as to call it a ‘paper tiger’. Yet, once again the demand was surfacing. And this time both the know-how and the requisite fissile material were closer at hand.

There are signs that Indira was seeking military assertion in other ways. In November 1970, she had asked the DRDO to launch a feasibility study on building a long-range ballistic missile. Two months before that she had apparently asked for a similar study on a nuclear-propelled submarine. As Chengappa observes, ‘Mrs Gandhi had laid plans for India to join the big boys’ club.’ But crucially, he maintains, some time in mid-1970 she had also asked Vikram to prepare for a nuclear explosion.

This appears to be accurate because the Morning Herald, Sydney, 27 July 1970, quotes Vikram as asserting that India was capable of conducting underground nuclear explosions and that it was internationally entitled to do so as a non-signatory to the NPT. Those who knew Vikram well maintain that he would not have disobeyed a direct order from the prime minister. The US, clearly perturbed, sent an aide-memoire in November 1970 indicating that using plutonium from CIRUS, the Canada—India research reactor, would violate the US—India nuclear cooperation agreement.

Privately, however, Vikram appears to have been torn apart. Kamla maintains that he was under tremendous stress at the time, particularly with regard to the prime minister’s advisers. I.G. Patel noticed a diminishing warmth and trust on Indira’s side towards Vikram. There is a suggestion that Vikram was deeply concerned about the potential fallout of these factors on his beloved space programme. Funds allocated under the Fourth Plan (1969-74) were half of what he estimated the space programme would need for the same period in his ten-year plan.

Characteristically, however, Vikram concealed his mounting agitation under an appearance of liveliness. In May 1971, he took a rare holiday with his family in Manali. A small house was rented in the valley and Vikram appeared to relax completely, playing golf, wandering in the town, eating noodles and playing with his grandson. There were security men in the bushes—he was the AEC chairman, after all—but, according to Mallika, they unwound too, flirting with her and teaching her to fire a pistol.

But the clock was ticking. The cost-benefit study on explosives that Vikram had commissioned from Seshagiri became available in 1971. The outcome could not have been to his liking; it showed that peaceful nuclear explosives for engineering purposes would be economically viable though weapons might not. The pressure was growing. Still, he did not show it outwardly. He travelled to Thumba and to Ahmedabad and though the perceived tussle over the bomb was well known enough for his colleagues to whisper about it, Vikram did not say much.

‘It was this Gandhian thing of self-sufficiency,’ says Mallika. ‘Look inside. Churn the depths of your spirituality. Mridulaben was also like that. Not being self-reliant was considered a weakness, a flaw in character.’ And yet, inside Vikram was crying for help. Sometime roughly between June and November of 1971, Mrinalini describes him getting up from his sleep suddenly in the middle of the night. ‘He went to the window talking incoherently about his work,’ she recalled.

This is an edited excerpt from ‘Vikram Sarabhai: A Life by Amrita Shah’. Excerpted with permission from Penguin Random House India.