Recovery is a key theme in Mammo. As Benegal notes, ‘It’s Mammo who he [Riyaz] wishes to recover from the past. The collision between the past and present, a recurring theme in the films of Benegal, strikingly dealt with in Trikal (Past, Present and Future, 1985), repeats itself in the recovery of the memory of Mammo. The device of recovery at a time when Muslims were increasingly under attack in the mainstream, expressly from Hindutva, reiterates how this cycle of films acts as a collective attempt to recover the Muslim in the imaginings of Indian cinema, which had become displaced and lost over time. Subsequently, the attempt to recover the Muslim and situate it more clearly in Indian cinema was an ideological intervention instigated by the inclusive social and political agenda of parallel cinema that also filtered through into subsequent mainstream representations of Muslims as seen in Fiza (2000, directed by Khalid Mohamed).

Recovery occurs instantly in Mammo. After Riyaz begins reading through the letters written by Mammo and which Fayyazi has been holding on to, the doorbell rings. Riyaz opens the door to reveal Mammo standing before him. But when we cut back to Riyaz, it is the younger version that is conjured before us, segueing seamlessly into a flashback. Through the letters, a tangible record of the past, Riyaz is quick to resurrect the memory of Mammo. This indicates that although the Muslim can be suppressed or demonised momentarily in the wider imaginings of a right-wing Hindu nationalist discourse, the Muslim can never really be erased completely from history or the nation because film as a cultural artefact, in this case parallel cinema, opens a new way for recovery and resistance.

Also read:

Benegal’s women: the muslim woman as a victim of partition

The recovery of the Muslim, first articulated in the opening to Mammo, is also closely linked with the Partition and the figure of the woman, since women ‘were in most cases the worst sufferers of the Partition. Benegal’s revisionist approach to history, a key thematic preoccupation of his oeuvre that forms the basis for many of his best films such as Trikal and Bose (2005), is also evident in Mammo. While the opening uses the flashback as narrative device to resurrect Mammo, the Muslim woman, the theme of the Partition, is brought into play straightaway with a compelling montage of fragmented images from the film. This is not necessarily a strategy of foreshadowing but the fragmented style creates a dissonance in which the theme of separation seems most potent, a visual link to the history of the Partition that bears down on many of the Muslim characters. Moreover, the fractured editing style personifies the theme of the Partition. In this opening montage, Benegal wants us to feel an overwhelming dislocation, something that is experienced by Mammo on a continual basis.

The conceptualisation of Mammo’s alienation and exilic status is expressly signalled when the montage segues into the first rendition of the ghazal ‘Yeh Faasle Teri Galiyon Ke’, which is juxtaposed with Riyaz waking in his bed. Now it becomes clear that everything we have just seen are the fractured memories of Riyaz who is haunted by Mammo, a symbolic link for the Muslim to a traumatic past, which remains intact. In this respect, Mammo’s status as a Muslim woman is augmented by the Partition; the two are inseparable. The sequence in which Mammo relays her memories of the Partition to Riyaz is an important moment in the film because it points to a historical rupture that re-organised communal relations between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, a traumatic wound that remains open.

Mammo begins by telling Riyaz that she has experienced hell; this is the way she refers to the trauma of the Partition, announcing that she should never have to witness it again. Harenda writes, ‘the whole act of Mammo providing her spoken testimony can be viewed in terms of double witnessing’. Mammo talks of having left behind everything in the dead of night and making the arduous cross-border journey to Pakistan. This oral re-telling of Mammo’s story of the Partition is one of the thousands of similar stories of suffering. The significance of the oral re-telling and passing of trauma to a new generation is chiefly important because this is the primary way in which the memories of the Partition have been kept alive, confined to a personal, secretive and familial space: In passing on this story to Riyaz, the child of a new generation, Mammo bears witness to that woman’s personal tragedy, a tragedy that implicated all who lived through those catastrophic times.

This is also the first time Mammo refers to herself as a refugee, talking of the horrors of what she witnessed, expressly the suffering, fire, blood and looting: There were around five hundred of us. While we were crossing over from this side just as many were coming across the other. From this side, the people were Muslims, and from that side, Hindus and Sikhs. But both sides went through the same trauma. Abandoning their homes, property, loved ones.

There was a woman walking along with me. She had two small children. They were in her arms. One died while in her arms. Where was the time for any burial? When we came to a river people told her to dispose of the dead body in its waters. The poor woman was not in her senses. She threw the live baby into the river and held the dead child strapped to her breast. Her worn and beady eyes are still before me, and her shriek. The allegory of the traumatised mother as a victim of the Partition functions as a logical expression of Mammo’s own experiences. And the imagery of madness conjured by Mammo to describe the lunacy of Partition links to Sadat Hasan Manto’s famous short story Toba Tek Singh (1955) that revolves around lunatics in an asylum in Lahore on the eve of the Partition. Not to mention, Mammo’s memories of the Partition are triggered by a conversation with Riyaz that talks of Manto as a writer. Rather than resort to an extended flashback that could have visualised the recollection, Benegal chooses to have Mammo positioned centrally in a medium close-up and talk directly of her experience, suggesting that it is a trauma from which she cannot escape.

The use of smoke, a concrete link to the past, that drifts across the shot of Mammo as she speaks is an unexpected moment of magical realism, deepening the inescapable nature of the Partition that locks victims into re-living a personal trauma. By the same token, agency is critical; letting Mammo speak of the horrors she has experienced, significantly as a Muslim woman, reiterates Benegal’s thematic commitment, which has been to articulate the voices of women often never heard or seen in Indian cinema. Indeed, the trauma of the Partition is not spoken in exclusive terms of the Muslim as victim, but speaks of a shared trauma that impacted Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims alike. In a sequence devoid of sentimentality, there are two pertinent shots that Benegal inserts into Mammo’s recollection which anchor the witnessing of trauma as something tangible for the film spectator. The first is an obscure panning shot of people at night fleeing in desperation as fire rages in the background. In many ways, this first shot denotes rioting and exile, stereotypical of Partition literature and films, situating Mammo’s story as part of a well-known historical narrative. But it is the second shot, a disturbing image, which is of real significance; ‘a naked baby moves on the body of the raped and dead mother’.

Albeit the image of the naked baby connects metonymically with the story that Mammo relates of the devastated mother, it arguably points to a repression that underlies the notion of memory. It is important to note that Mammo never describes this image in her oral recollection to Riyaz; it is an image that Mammo shares only with us. Benegal seems to be suggesting how memory is fractured, incomplete and bound to the context in which it is recalled, an idea tied to narrative subjectivity that forms the basis of Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda (The Seventh Horse of the Sun, 1992), Benegal’s masterful take on the trope of the unreliable narrator and one of his most reflexive and open works. A final means of framing the Partition is through a reflexive gesture. When Mammo, Riyaz and Fayyazi visit the cinema, the film they go to see is Garam Hawa.

As noted earlier, Garam Hawa, written by Shama Zaidi, also contributed to the script of Mammo. The importance of cinema-going as a cultural ritual is an autobiographical aspect of both Benegal’s and Mohamed’s childhood and it is a motif evident in Riyaz’s attempts to bunk off school to go and see Hitchcock films at the local cinema. Remarkably, the scene from Garam Hawa that Benegal chooses to use in Mammo is the one when the ailing matriarch dies in the ancestral house. Before her death, Salim Mirza pleads with the new landlord, an old friend, that his mother is very ill and wants to return to the ancestral home for a final time. The grandmother’s desire to return to the home where she was born is mirrored in Mammo’s similarly arduous plea to return home to India.

Since the victim often has to relive the trauma of the event, the trauma of Partition that Mammo carries with her is symbolically reenacted towards the end of the film. And it is the act of separation that resurfaces when Mammo is dragged out of her sister’s home, led away by the police, forcibly put on a train and deported back to Pakistan. Priya Kumar argues that ‘the film testifies to the enduring official inheritance of Partition which ensures that survivors like Mammo will not be allowed to transgress the boundaries that have been demarcated for them’. Perhaps the only way to circumvent or counter the ways in which the Partition marks Mammo is through the total erasure of identity and her very existence, an area of discussion that will take up the final section of this chapter.

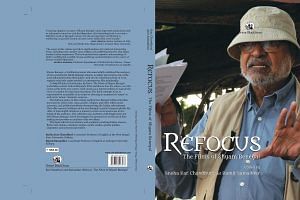

This excerpt from Omar Ahmed’s essay in ‘Refocus: The Films of Shyam Benegal’, edited by Sneha Kar Chaudhuri & Ramit Samaddar, has been published with permission from Orient Blackswan.

This excerpt from Omar Ahmed’s essay in ‘Refocus: The Films of Shyam Benegal’, edited by Sneha Kar Chaudhuri & Ramit Samaddar, has been published with permission from Orient Blackswan.