Understanding Rajkumar as a cultural phenomenon is a seriously difficult task: the dimensions of his presence in Karnataka are so many. A moral icon, a folk hero, a voice, a force, a natasarvabhouma (“the Emperor of Acting”): these familiar ways of pinning him down convey the complex cultural persona of the Kannada superstar.

It is unlikely that another film actor in the country has matched the variety of roles Rajkumar played. Appearing in 220 films across five decades, he has done lead roles in historical, mythological, devotional, romance, action and espionage thrillers, and family melodrama, among other film genres. In what is surely an uncommon cultural fact, Kannada film viewers have experienced a diverse range of genre settings through the figure of Rajkumar: they have seen them through his eyes; they have felt them through his body.

Between 1953 and 2000, the release years of his first and last films, Bedara Kannappa and Shabdavedi, respectively, Rajkumar can be seen forging continuities between the past and the present and the future of Kannada society. The continuities in the community selfhood run through political-military episodes, exemplary lives of saints, mythological drama and the so-called social films.

The past was more squarely the past of Karnataka in the case of historical figures from this region—for example, Krishnadevaraya, the emperor of Vijayanagar, Kaivara Tatayya, the saint, and Ranadeera Kanteerava, the king of Mysore. Then there are the figures that Karnataka could lay claim to as being part of a sub-continental region— for example, Kalidasa, Kabir, and mythological characters like Arjuna and Ravana. Indeed, popular memory in Karnataka recalls the visual images of Satya Harishchandra and Immadi Pulakesi, the Chalukya emperor, from his films. The films of Rajkumar supplied durable images and sounds for numerous historical and mythological episodes. While history books reached schools and colleges as a set of dull details of dates and proper nouns, the historical, mythological and devotional films of Rajkumar brought the past to life for large numbers of people in a resonant way. The sets were grand; the dialogues were grand; the acting was grand: they vivified the past in ways that bewilder sober historians. Initially a theatre actor at the famous Gubbi Nataka Company, the timing and pitch of Rajkumar’s delivery of stylized speech in these films was unmatched.

Also read:

In films set in contemporary times, Rajkumar moves smoothly across both modernity and tradition. He visits temples, does puja at home, does the duties expected of a son, a lover, a husband and a parent. In other words, he is not embarrassed about traditional ways of being in the world. At the same time, he is comfortable in suits, in modern professions, in using modern technology, and more generally, in navigating modern spaces without melancholy, pathos, nostalgia or anxiety.

In his most famous film, Bangarada Manushya (Man of Gold, 1972), for instance, he deploys tractors and bore-well drills to make dry land cultivable for modern agriculture. Again, in an earlier film, Operation Jackpotnalli CID 999 (1968), which was inspired by the James Bond thrillers, the Secret Agent’s secretary asks the Police Chief to call back later as he was doing yoga at the moment. And, Rajkumar’s ability to speak in English in modern-day film settings is never in doubt. What he will never let pass though is anyone using English for status games, for making Kannada appear an inferior language.

On a broad glance, Rajkumar’s films, in particular, those that he did after acquiring superstar status, work as a custodian of Kannada morality. Whether set in the historical or mythic past or in the rural or the urban present, the characters played by Rajkumar will affirm the values of self-restraint, kindness, humility, justice, tolerance, compassion and respect for others and refute arrogance and violence. They will be non-elitist and hold up the value of civility and refrain from peddling hatred. Being courageous rarely lapses into militant self-pride.

Not aligned with any denominational religion or sect, these values are worked out in a general sense in Rajkumar’s films. A crucial feature of these films pertains to their edificatory content. A Kannadiga NRI parent in the US once told me that he had made his young son watch Gandhada Gudi (The Sandalwood Shrine, 1973), where Rajkumar plays an honest police officer, several times as that hit film imparted good values. The director of a documentary on the film superstar admitted that the motive behind the film was to impart good values to Kannadiga children, especially in NRI families. Clearly, Rajkumar’s films are not wholesome entertainment alone: they also extend lessons in self-edification. It would be incorrect however to view Rajkumar’s films as affirming a consistent set of values.

On occasion, the roles he played held out moral lessons within the framework of karma siddhanta and divine predetermination (“Yene Aaadaru, Avana Kaanike,/Whatever happens, it is His gift,” is the refrain in a famous song in Premada Kaanike (A Token of Love, 1976)). On other occasions, they exhort the audience to take charge of their lives without an accompanying idea of karma. The famous song from Bangarada Manushya is a good illustration: “Aagadu yendu, namigaagadu yendu, kai katti kulitare, saagadu kelasavu munde, manasondiddare margavu untu/Saying it can’t be done/saying it can’t be done by us/if we don’t do anything/ the work won’t get moving/Where there is a will, there is a way. Apart from the song lyrics, heeding the work of the scriptwriter, cameraman and the director will all form a part of the task of grasping the film phenomenon, “Rajkumar.”

Rajkumar’s films show a care for building a Kannada samaja (society), and not a Kannada rashtra (nation) as such. He played the roles of royal personages many times but hardly ever that of functionaries of the modern state. Apart from the occasional role of a mayor, in Mayor Muthanna (1969), or that of a police officer, Rajkumar is not found playing a politician or bureaucrat or judge in ways that emphasize the value of the modern state or the rule of law.

In Raajakumara (2017), when its hero and Rajkumar’s son, Puneeth Rajkumar, is asked to join politics, he replies: “Father always used to say: ‘Those who rule over people need political power. We care for people. Willpower suffices for us.’” This response strove to explain why his father stayed out of electoral politics. Following his support for the Gokak movement in the early 1980s, which sought primacy for Kannada language instruction in state-run schools and job reservation for Kannadigas, Rajkumar became a symbol of the activist dreams of the Kannada movement. He desisted however from moving towards party politics.

Through the mysterious process which frees individuals from their community identity in people’s eyes in India, Rajkumar, who came from the Idiga community, a toddy tapper caste, belonged to all. When held hostage inside a forest by Veerappan, the smuggler, for over three and a half months in 2000, the uncertainty over his safe return kept everyday life in the state tense the entire time. No one else could have drawn such levels of concern. As superstar, as voice, as image, Rajkumar is an intimate presence in the lives of Kannadigas. Whether they admire him or not, he remains a deeply familiar point of reference, a point of entry into a world of belonging.

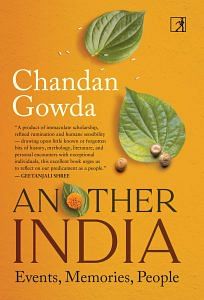

This excerpt from Chandan Gowda’s ‘Another India: Events, Memories, People’, has been published with permission from Simon & Schuster India.

This excerpt from Chandan Gowda’s ‘Another India: Events, Memories, People’, has been published with permission from Simon & Schuster India.

Dr Raj, annavru – like none other. He should have received Bharata Ratna award for sure.