If there was one ethos that cut through the various nationalist-ascetic narratives, it was the idea of Seva or service. So integral was the idea of service to both Gandhian and Hindu nationalist practice that it became a core value of nationalist consciousness. Drawing much of its content from Vivekananda’s teachings and Gandhi’s practice, many freedom-fighters like Jagat Narain believed that in Seva lay the route to both individual freedom and social transformation. From Vivekananda, he imbibed that he who directs his activities to the service of man—the manifestation of God upon earth—is a true karmayogi. ‘He who sees Shiva in the poor, in the weak, and in the diseased, really worships Shiva; and if he sees Shiva only in the image, his worship is but preliminary.’ ‘If you want to find God, serve man. To reach Narayana, you must serve the Daridra Narayanas—the starving millions of India. Charles Heimsath reads Vivekananda’s Vedantic revivalism as a critical moment in the progress to universal nationhood.

The idea that ‘service’ to humanity, would simultaneously lead to reformation of the social structure and amelioration of the depressed classes and to individual freedom/ salvation held tremendous potential as a transformative tool for nationalist aims. However, while Vivekananda focused on grihastha as the site of activism, inheritors like Jagat Narain scaled it up to make the nation a site for service. Seva in the context of the national movement began to embody ideas of the nation and the nation’s goals. Large numbers of students who left educational institutions in response to Gandhi’s call for boycott of educational institutions during the Non-cooperation movement (1920–22), began to join seva samitis and take part in their village organization work. ‘By the end of 1920s the Seva Samitis proliferated in every district of Bihar. By April 8 [1921] there were 7860 volunteers and by June, the number reached 10,319. Nationalist propaganda work too came to be vested almost entirely in the hands of these volunteers.’

But the shift was not just in scale of seva operations—it was also in its meaning. While the religion-neutral idea of seva— that loosely implied service, welfare, social and constructive work—remained in use, the idea of seva was beginning to get narrowed down. It was beginning to serve and represent various Hindu interest groups and community positions, all geared in different ways to the revivalist ideology of its key actors. Seva may have begun as a form of social work, but soon, in many formative ways, the idea of seva became a ‘Hindu practice’, forging a conflation of devotional and religious identity with the aims of the nation. The idea that ‘Hindu interests’ on their own formed a nationalist agenda soon crystallized into the more exclusive conception of Hindu nationalism.

What started as an idea of seva, a positive sensibility associated with preserving the interests of the community, became a communal concern symbolizing an exclusionary sentiment that aimed to compete with and defeat the ‘other community’. For example, in the aftermath of the Kohat Riots of 1924 in NWFP, Lala Lajpat Rai (who had founded the Lok Sevak Mandal in Punjab in 1921) advocated a partition of Punjab along religious lines, suggesting that this would be between a Muslim India and a non-Muslim India. Shortly thereafter Lajpat Rai resigned from the Congress and was nominated as the president of the Hindu Mahasabha in 1925. ‘Insisting that “unity cannot be purchased at the cost of Hindu rights”’, Lala Lajpat Rai fought the 1926 assembly elections, as the founding member of the Congress Independent Party, along with Jagat Narain Lal, against the Congress on a largely Hindu nationalist plank.

On his release from jail in July 1922, one of the first things Jagat Narain Lal did was to resume his responsibilities at the Bihar Provincial Seva Samiti, of which he had been the general secretary since 1918–19. In his words, ‘One of its chief activities was rendering of social service at the great Harihar Khetra fair, held annually in Sonepur on the occasion of Kartik Purnima, some time in November, with the help of several hundred volunteers.’ As a member of the Samiti, Jagat Babu also involved himself with the All India Go-Seva Mandal which was concerned with issues of cow protection (goraksha). He joined forces with Jagannath Barhe and Lakshman Narayan Garde to make the Harihar Kshetra the all-India centre for goraksha work and to organize an all-India conference under the presidentship of Shankaracharya Bharti Krishna Tirtha.

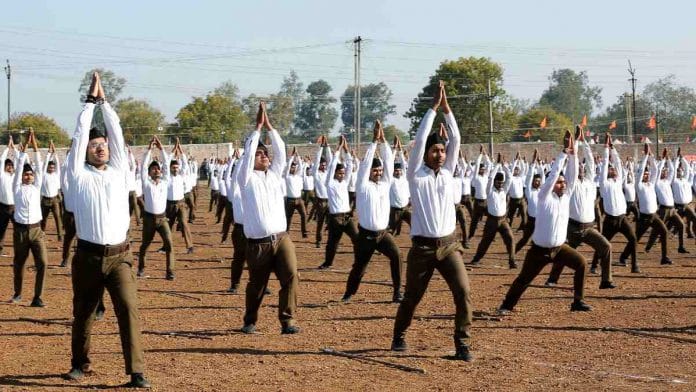

The religious and socio-cultural aspects seemed to merge in the idea of seva, often abetting a collective psyche of persecution and a shared, exclusive identity. Together with the Hindusthan Seva Sangh, which Jagat Babu founded in 1930, almost all the existing seva dals—Swayam Sevak Dal, Rashtriya Sevak Sangh, Servants of India Society, Servants of Hindu Society (Hindu Sevak Samaj)—took on shades of meaning beyond the idea of simply community service to also include ‘religious work’. The call was for a missionary attitude and the spiritualization of public work (the context of Christian missionary conversions often providing the impetus and the provocation, as I shall shortly discuss in the case of Jagat Narain Lal). These seva samitis become essentially ‘Hindu’ organizations, taking up issues of cow protection, ‘music before mosque’, Hindi language, and sometimes reform campaigns for the removal of untouchability, mutt (temple) reforms and so on.

Also read: RSS roadmap before it turns 100: New debate on freedom struggle & radical Islam, expansion

A word about the Hindusthan Seva Sangh is in order, for it reveals Jagat Narain Lal’s vision and version of service. He had long wanted to organize, to quote him, ‘a missionary institution working on the lines of the Servants of India Society, founded by late G.K. Gokhale’. He nearly joined Lajpat Rai’s Lok SevaMandal (Servants of People Society) but at the last moment discovered that it would not accommodate anyone with his ‘particular views’. In 1932, Jagat Babu joined B.S. Moonje’s Servants of Hindu Society, set up after Lajpat Rai’s death in 1928 to memorialize him, but he soon ‘found it impossible to fit [him]self into the scheme. He goes on to clarify what he was looking for: ‘I could pledge life-long allegiance only to an institution that stood for the ideal of service to the Hindu Community, to the country and to the world at large in a selfless spirit of dedication to the Lord. For this I need fearless, god-intoxicated men with a passion for threefold cause, men who had faith in God and were prepared to die for their ideals— only such as these could be my comrades’. He discussed this project with several of his colleagues in jail, and proceeded to establish the Hindusthan Seva Sangh, soon after his release from jail in 1930.

But what really became the converging point for all these different seva campaigns—were the shuddhi (purification and reconversion) and sangathan (organizing the Hindus into a band of political volunteers) campaigns. By the mid-1920s, the idea of seva had a acquired a missionary zeal and had aligned with the shuddhi and sangathan campaigns of Hindu right-wing organizations like the Hindu Mahasabha, the RSS and its many affiliates. The belief that Hindu culture, its religious practices, its purity and holiness, was in danger from the political machinations of the British, from the ‘evangelical zeal of missionary Christians’, from ‘virulent Islam’ and from Macaulay’s ‘agnostic liberals’ became the ideological impetus for the programme and content of the Hindu Mahasabha, of which Jagat Narain Lal became a member in 1922. That these faultlines would remain embedded in our national bedrock was not imagined at the time.

Extracted with permission from ‘Competing Nationalisms: The Sacred and Political Life of Jagat Narain Lal’ by Rajshree Chandra, published by Penguin Random House, India.

Extracted with permission from ‘Competing Nationalisms: The Sacred and Political Life of Jagat Narain Lal’ by Rajshree Chandra, published by Penguin Random House, India.