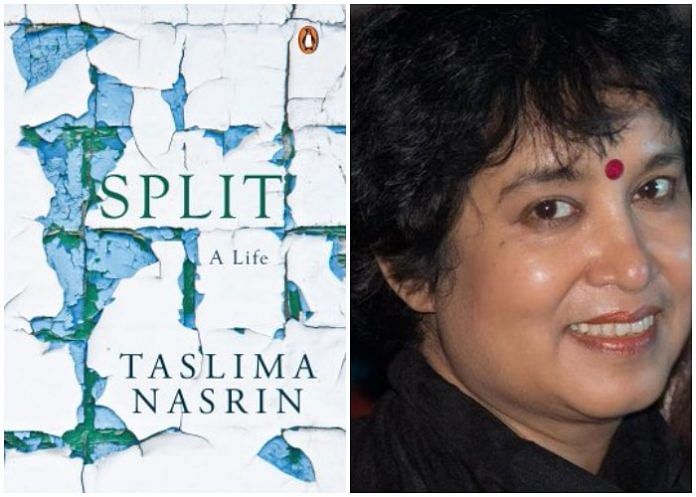

In this excerpt from her book Split, which was once banned in West Bengal, Taslima Nasreen talks about her most famous work Lajja, the response she received, and the impact of the BJP translating the book.

I did not write Lajja because I wanted to have it published from West Bengal. I wrote Lajja for Bangladesh. The book had caught the attention of Ananda Publishers only after the pirated copies reached West Bengal. The authorities at the publishing house took the help of the police and got some of the counterfeiters jailed eventually. I did not ask them what had dictated their actions— ethics or business. The manuscript taken by Mostafa Kamal was the first official manuscript I sent to Calcutta and Ananda Publishers published Lajja in West Bengal.

A ban was perhaps a contagious thing. News arrived that Lajja had also been banned in Sri Lanka though there was not one reason I could think of why the book should be banned there. There was no end to the debate over the book either. The conversations went on everywhere, on the road, in trains and buses, at homes and offices, courts and markets and public grounds . . .

One day Shamsur Rahman, Nirmalendu Goon and Bilal Chowdhury were at my house when the talk invariably veered towards Lajja. Pushing a copy of Inquilab in my direction Chowdhury said, ‘The BJP has apparently published Lajja. They have gotten it translated too.’

‘The mullahs are blaming Taslima for the fact that the BJP has published or translated the book,’ Goon interjected, ‘but how is this her fault? If Golam Azam loves my poetry will that be my fault too?’ I intervened. ‘How can the BJP translate the entire book? There are many things in the book against them.’

The only criticism Shamsur Rahman had against Lajja was that despite everything the book failed to provide a complete picture of the movements that were continuously battling the forces of communalism and the fact that there were secular individuals too in the country. I accepted his point and told him that my wish had been to narrate the story from the point of view of an angry Hindu boy to whom none of the secular and non-communal movements were of any help. On the BJP, Rahman remarked, ‘Just see how they are trying to turn something completely non-communal into a communal issue. Debesh Roy of Calcutta has written a novel from the point of view of their Muslim minorities, does no one here notice that?’

Goon burst out laughing. ‘The mullahs are saying the BJP has paid Taslima Rs 45 lakh to write Lajja. So, Taslima, aren’t we getting a cut too? Or do you want it all?’ Laughing, I replied, ‘Inquilab is writing this, isn’t it? Now even the common people believe that the BJP has actually paid me money!’

Shamsur Rahman was having none of it. ‘It’s so easy, is it? Just saying you’ve been paid off? Why aren’t they proving it then? Before the elections the BNP had accused India of paying Rs 500 crore to Sheikh Hasina. The Awami League had shot back with a 600 crore offer from Pakistan for Khaleda Zia. Neither has been able to prove these accusations yet.’

I could not help but agree with him. ‘And they will not be able to prove their accusations against me either, that I was paid to write Lajja. But what I am wondering is why are they out trying to slander me? Have the political parties paid them off ?’

Throwing the copy of Inquilab aside with a curse Chowdhury burst out, ‘More than the Hindus it is the Muslims who have benefited from Taslima’s Lajja. The book is an example of how compassionate Muslims can be. To speak on behalf of the minority despite belonging to the majority, that too so boldly and insistently, is not something you get to see too often. Muslims can probably use this when the time is right, to show how open-minded they can be.’

Laughing at his suggestion I countered, ‘Bilal bhai, so easily you have turned an atheist like me into a Muslim!’

‘Aren’t we all atheists? Since you have a Muslim name they will slot you as a Muslim. That way no one is an atheist here. You’re a Muslim or a Hindu, a Christian or a Buddhist. Religion is a must.’

I turned to Shamsur Rahman. ‘Religion is the culture of the uneducated, and for the educated culture is religion. Isn’t that so, Rahman bhai?’

‘Who do we call educated?’ Rahman replied. ‘Golam Azam is an educated man, so is MF. Both have university degrees.’‘No, no, I’m not talking about academic education,’ I hastily added. ‘Even a person who has never gone to school can be educated. Take for instance Araj Ali Matubbar.’ Chowdhury, who was a great admirer of the self-taught philosopher and rationalist, excitedly joined in at once. ‘Araj Ali was a poor farmer. But look at the beautiful books he wrote. His books should be taught at school.’ Shamsur Rahman nodded at the suggestion and added, ‘Not just schools, they should be part of the syllabus in colleges and universities too. Reading his books will help people raise pertinent questions about religion and many will find inspiration in them to embrace atheism.’

Kulsum came in with tea and everyone picked up a cup. Meanwhile, Dr Rashid had come in and silently taken a seat. He used to be an active member of the JASAD35 but recently his role had taken a more passive turn. A sharp and rational individual, Dr Rashid was staunchly against any form of communalism, superstitions and religious dogma. While sipping tea I pondered on a more immediate question: Were all our problems going to disappear if the Muslims were to turn atheists?

Somehow I was not convinced by such a quick fix. I was convinced that someone like Golam Azam was an atheist too and the same went for all the leaders of the Jamaat. It was their followers, the foolish gullible disciples, who were the true believers. These were the people who were being led by the noose of religion around their necks, for people like Golam Azam to play their political games. Keeping the tea aside I turned to Shamsur Rahman. ‘I believe Golam Azam is an atheist. Take Ershad for instance. Do you think he believed in religion? The way he suddenly amended the constitution and made Islam the state religion, do you think he did it out of his love for Islam? Of course not. It was a clever use of religion to serve the needs of power.’

‘Yes, this is what political Islam is all about. I too believe that the people who use religion for politics know very well how effective it is in keeping people stupid and docile. It is highly unlikely that people who use religion for their own benefit believe in it themselves.’

‘Even if we assume they do believe, it should be noted that ultimately they are adhering to the tenets of Islam. In Islam the world is divided into two: Dar al-Islam and Dar al-Harb, the land of the Muslims and the land of the non-believing others. The sacred duty of Muslims is to invade the Dar al-Harb and convert the people to Islam by whatever means necessary. So the ultimate target is to transform the entire world into Dar al-Islam. Then whatever the Bangladeshi Muslims are doing is perfectly according to the principles of Islam. Islam condones such acts.’

‘That’s not exclusive to Islam. Even Christians had the same principles. Just see where they started and how far they have spread!’

‘True. Most monotheistic faiths have a horrifying history. But Rahman bhai, why even now? Why are we being subjected to acts of cruelty that can only be termed medieval even at the fag end of the twentieth century?’

‘Because we still haven’t managed to become human.’

‘But the Christians no longer rabidly pursue a policy of slaughtering the other. Why have the Muslims held on to it?’

‘Because most Muslim nations are yet to embrace secularism, like most Christian nations have.’

‘But there were movements on that front too. Consider the pan-Arabism movement for that matter. It was a secular movement.

Almost everyone concerned from the Arab countries were Muslims.’ ‘The derailing of the secular movement in the Arab countries is squarely the responsibility of a few evil Arab leaders, although even they are puppets of imperial powers. None of the imperial powers could tolerate a big movement in any of their colonies, especially the ones that directly challenged their power and authority.’

‘But, Rahman bhai, the pan-Arabism movement came into being after the colonial powers had left.’

At this juncture, Dr Rashid intervened. ‘How far did the imperialist go? Somehow or the other their greed for oil made sure they stayed in the Middle East in some form or the other. Who controls the oil reserves? It was always the British, before the Americans replaced them. Did the leaders of pan-nationalism fight any less to nationalize the oil reserves?’

‘Fundamentalist movements like the Islamic Brotherhood grew out of a rebellion against such imperialist forces. They too have a role in destroying any chance at a secular uprising,’ I added.

‘The Arab leaders could not unite because they were busy fighting each other. Nasser of Egypt had wanted to unite all the Arab countries but the other nationalists rejected the idea. If the Arab countries had united, could an American or British have dared to try and put a puppet in power and pull all the strings from the shadows?’ Dr Rashid was agitated and gulped down the cold tea in front of him.

‘This growing tide of Islamic fundamentalism in the Middle East, is it because of the Israel–Palestine issue? Or is it because of the Berlin Wall? The Wall has fallen, the irreligious Soviet Union has fallen too. Does that imply ideals of secularism have fallen too? Hence, awake and arise religion! O great Islam . . .’

Chowdhury interrupted and said, ‘The history of the subcontinent is different, here fundamentalism has been strengthened primarily by state complicity.’

I agreed with him. ‘Of course. But fundamentalism is contagious. It spreads from one place to another . . .’

‘These Jamaatis in Bangladesh are pandering to . . .’ Shamsur Rahman had angrily just begun when his words were interrupted by a sudden knock on the door. His unfinished sentence hanging in midair, Rahman turned to look at the door as Dr Rashid got up to answer. All our senses had zoomed in on the door. Everyone was aware that it was not a good idea for a stranger to casually walk into my house. Every Friday there were meetings in the mosque where people were abusing me and protest marches were held demanding the noose for me. Such was the time that any devout Muslim could barge into my house any time and murder me. Was it someone like that? Or else why was Dr Rashid hesitating to let them in and guarding the door as he spoke to the strangers beyond the threshold? After talking to the unseen guests a while longer he turned, leaving the door ajar, and said, ‘Four boys from Shani’s akhada are here to see you.’

‘Who are they? What do they want?’

‘You won’t know them. One of them is Shankar Ray.’

Goon immediately said, ‘Don’t let them in. Close the door. They could just have assumed Hindu names and come here with ulterior motives.’ After a pause, he laughed and said, ‘But then you can’t trust the Hindus either, can you?’

Dr Rashid went back to the door, softly spoke to the men outside again and then turned back to me and said, ‘They are perfectly harmless simple men. They have just come to pay their respects. They will go away after that.’

More out of curiosity to know who they were and why they were at my house, or perhaps also out of a sense of security that there were many people present who would rescue me if something untoward happened, I replied, ‘Fine, ask them to come in.’

Four young men entered the room, all of them within twenty to twenty-five years of age, in simple clothes and sandals. They took off their sandals near the door, looked around the room once and then lowered their hands towards my feet. I jerked my feet away and stood up. Even before I could say anything the boy called Shankar stood in front of me with folded hands and said, ‘Didi, you are like a goddess to us. We feel blessed to meet you. We’ve looked everywhere for you. We wish to touch your feet once.’ But I moved my feet away again when he tried the second time. Shankar pointed to the two other boys and said, ‘These are my cousins’, and then pointing to the third man in a red shirt, he said, ‘He is a friend. We are all in college, didi.’ When he tried lowering his head for the third time I said, ‘No, you don’t have to touch my feet. I don’t like these things. Tell me what you want to say.’

‘Didi, we have read your book Lajja. No one has ever spoken on behalf of us like this before. Didi, what you have done, if only you knew how great . . . you have written what has always been in our hearts.’

‘See, it’s not a Hindu–Muslim thing at all. As a human being I have written about the pain of other human beings around me. Everyone you see here, all of them are writers and they have all spoken out against social injustices.’

Published by special arrangement with Penguin India.

Voice of Jihadists don’t worry