The first major cause of friction between Assam and New Delhi in the post-Independence era was over the settling of Hindu refugees from the newly created East Pakistan. By 1950, Assam had already provided shelter to around 3 lakh displaced people from the region. Nehru threatened to halt financial aid to Assam if it continued to oppose the settlement of more refugees. He seemed to not be concerned that Assam was already reeling under a severe economic crisis after Partition. After Independence, Assam had been transformed into a landlocked state after the closure of the centuries-old commercial arteries through land and river that linked it with East Bengal. The tea sector could hardly be expected to contribute to the local economy, since it continued to remain the garden of resource extraction, as in the colonial days. The state’s leaders appropriately perceived that Assam would continue to remain backward without industrialization. For them, establishment of oil refineries in the state was part of the answer to revive the flagging regional economy.

But it was too late. The Centre had already made up its mind to divert the crude oil from Assam to a refinery in Barauni in the state of Bihar. The decision sparked the first popular agitation in Assam in 1957 in the post-Independence period, which was supported by all parties. The Centre was compelled to sanction a mini-refinery with a much reduced capacity in Guwahati. The tremors from the agitation had hardly diminished when the People’s Liberation Army (China) marched through Arunachal Pradesh and knocked at the doors of Assam.

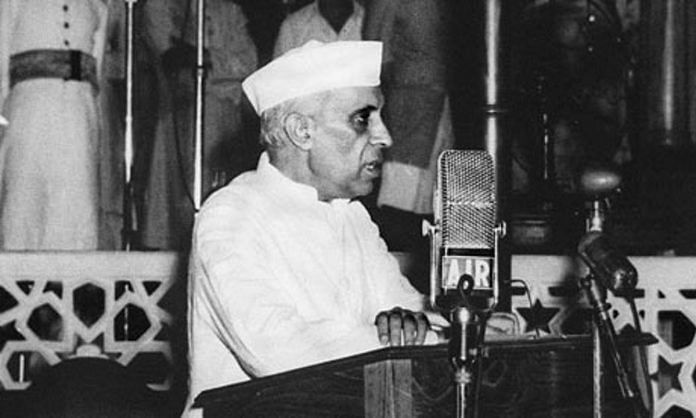

Prime minister Nehru delivered an emotional speech, which was misinterpreted to mean that he had resolved to leave the region to the mercy of the Chinese invaders. Fortunately, the PLA withdrew, but the episode was followed by greater turbulence in the state on issues ranging from language, price rise to economic underdevelopment, reinforcing the assumption that agitations were a precondition for wresting concessions from the Centre or for securing any legitimate right.

And, as if this was not enough, the Bangladesh War of Liberation (1971) brought in continuous waves of Hindu refugees from East Pakistan, aggravating the indigenous communities’ insecurity about being outnumbered by the immigrants. According to one estimate, over 100 lakh refugees crossed over to Assam during the war, out of which about 10 lakh never returned. Vast tracts of land continued to be occupied, reducing the per capita agricultural holding by 26 per cent in Assam, which was much higher than the national average decline of 16.7 per cent during 1961–71. Nor were there any signs of improvement in the state’s economy, despite the flourishing condition of the tea, plywood and oil sectors and the huge revenue garnered from them by the Centre.

Not surprisingly, unemployment soared in Assam in the absence of adequate opportunities. Between 1971 and 1980, the number of educated unemployed persons rose by 343 per cent, comprising almost 40 per cent of job seekers registered at the Employment Exchange in the state. Predictably, there was a drift again towards extremist ideas, which found expression in the birth of the Lachit Sena in the late 1960s and the attacks on Marwari traders in Guwahati.

In some meetings, the refrain of ‘Assam for the Assamese’ and occasional outbursts justifying sovereign status for the state were also heard. So, by the mid-1970s, conditions were ripe in Assam for a full-blown agitation again. The trigger came in 1978, with the Election Commission’s notification for revision of the electoral rolls after the demise of member of Parliament Hiralal Patowary, who represented Mangaldoi. In the process, as many as 36,780 foreign nationals were deleted from the rolls, which not only came as a surprise but also prompted the state government to extend the operation to eighty-one assembly constituencies.

However, the Election Commission issued orders halting the exercise after elections to the Lok Sabha were announced, which meant that lakhs of foreign nationals were being allowed to cast their votes as Indian citizens. Civil society groups swung into action, constituting the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) to oppose the Commission’s order. The bugle was sounded for a movement that eventually turned out to be the biggest mass upsurge in India in the post-Independence period. The historic agitation erupted against the backdrop of almost two centuries of crises in Assam, which stemmed as much from colonial policies as their continuation in the post-Independence era. Although the movement’s primary demand was identification and expulsion of foreign nationals, the yearning of the masses was also for resolution of the issues that had festered since time immemorial.

There was a large section that participated with utmost passion in the movement but was also convinced that an alternative path beyond agitations was imperative to coerce New Delhi to redress Assam’s grievances. They drew inspiration from the burgeoning secessionist movements in the neighbouring states of Nagaland, Mizoram and Manipur, where government security forces were engaged in a bitter combat with them and were employing aggressive tactics to bring the situation under control.

This excerpt from Rajeev Bhattacharyya’s ULFA: The Mirage of Dawn, has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Rajeev Bhattacharyya’s ULFA: The Mirage of Dawn, has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.