The US opening to China in the summer of 1971, heralded by Henry Kissinger’s secret trip to Beijing in July 1971, has been romanticized and celebrated in American and Western annals. In India, the trip was vilified and demonized. With time, the triumphalism associated with it in the US and elsewhere has meliorated and the opprobrium attached to it in India has softened. Fifty years on, how shall we assess it? China opening played a role in the ending of the Cold War, though the Soviet Union played the decisive part in its own destruction. The normalization of US-China relations also played a role in China’s rise. However, Kissinger was hardly the main architect. Much of the credit on the US side should go to the presidents that succeeded Richard Nixon and the National Security Advisors (NSAs) that followed in Kissinger’s wake. The US sowed the seeds of China’s rise for forty years, and now it and others must deal with Chinese power as never before.

Having said that, the next century will not be a Chinese century. The future will be bipolar, with three bipolar possibilities—the most likely being one that Kissinger would have been familiar with, namely, regulated competition. As for India, it missed the signs of the sudden rapprochement in 1971. It must be attentive to the signs of the US once again possibly changing course with China. It is good to remember that the US has long had a fascination with China. Even in these times of Sino–US conflict, the American interest in, knowledge of, and linkages to China are far greater than with India.

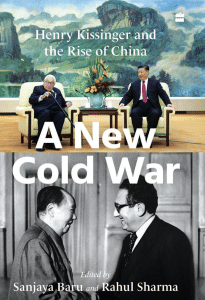

Kissinger and the opening to China

Henry Kissinger is credited with the opening to China in 1971, but it would be more accurate to say that he was ‘associated’ with it. America’s decision to normalize relations with China was already in process before Kissinger became Richard Nixon’s National Security Advisor: the thought of a strategic opening to China can clearly be traced to the Kennedy and Johnson administrations in the period 1961 to 1965. In any case, it was Nixon more than Kissinger who conceptualized the move. And it was President Jimmy Carter and his NSA, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and then President Ronald Reagan and his team who laid the foundations for the lips-and-teeth relationship that was to develop for the rest of the Cold War. Kissinger’s informal advice to US presidents and Chinese leaders, his voluminous writings and his consultancy work may have done more for US–China relations than his policy interventions in office.

As early as 1963, the US was already working on a degree of normalization with China. Washington was aware of the Sino–Soviet rift of the late 1950s and sensed an opportunity. In 1961, when he took office, President John Kennedy wanted to move beyond the diplomatic stalemate with China under his predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower, but given the narrowness of his victory in the presidential elections, he held off. Even so, a policy review was quietly begun. The slow churn on China might have led to some ‘breakthrough’ initiatives in December 1963. With Kennedy’s assassination in November those moves petered out. Nevertheless, in December 1963, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs Roger Hilsman gave a speech where, in Joanne Chang’s words, he ‘urged Americans to take a realistic view of the PRC, asserting that the Communist regime was here to stay and recognizing the possibility that the PRC would evolve into a more moderate state’.

Kennedy’s death slowed down but did not altogether stop the winds of change. By 1965, President Johnson was already easing the travel ban and the restrictions on Chinese journalists—if this had little effect, it was because Beijing was not ready for an opening. Indeed, under Johnson, relations worsened due to the full-blown US military intervention in Vietnam. The anti-war protests at home doomed Johnson’s re-election hopes, and in November 1968, Nixon, defeated by Kennedy in 1960, won the presidency. As early as October 1967, he had penned an article in the US journal, Foreign Affairs. Titled ‘Asia After Viet Nam’, it argued for the necessity of engaging China. Nixon’s clinching argument was that ‘Any American policy toward Asia must come urgently to grips with the reality of China … Taking the long view, we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors.’

Between March and September 1969, China and the Soviet Union fought a series of battles along the Ussuri River over their unsettled border claims. The fighting started after the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) ambushed Soviet forces. The emerging strategic convergence between the US and China may well have emboldened Beijing to precipitate matters with Moscow. In the event, the Soviets, rather shaken by the Chinese attack, were stirred to contemplate radical action including a possible joint nuclear attack with the US on Chinese nuclear forces. The US refused. China meanwhile decided that it needed a tacit alliance with the US. A complex process of signalling between the two sides ensued.

Looking back on it, quite a bit of the process leading up to Kissinger’s trip in July 1971 was jejune if not comical. A Chinese media account describes some of the communication that went on in 1970. First, Chinese leader Mao Zedong invited American journalist and writer Edgar Snow to stand on top of the Tiananmen gate to watch the National Day celebrations, a privilege never granted to a foreigner before. Then, President Nixon announced rather mawkishly during an interview with Time magazine, that ‘If there is anything I want to do before I die, it is to go to China. If I don’t, I want my children to.’ This was followed by the comedy of the US table tennis team meeting their Chinese counterparts in a tournament in Japan and asking to be invited to a subsequent tournament in China. The request was turned down until an American and Chinese player descended together from the Chinese team bus grinning in front of reporters. When Mao saw the picture of the two players, he ordered the Chinese team to accept the American request. The US team finally played in China in April 1971, and no less than Zhou hosted a reception for them. The Chinese also ensured that some of their players lost to the outgunned Americans—mocking their rivals and befriending them at the same time!

These and other—more serious—signals led up to Kissinger’s incognito trip to Beijing, with its near-farcical elements. The trip was hilariously codenamed ‘Marco Polo’. Before he went to the airport, Kissinger suddenly feigned heat sickness and was taken to Pakistani President Yahya Khan’s retreat outside Islamabad to ‘recover’. Later, he was to go to the airport with his face covered in a scarf and sunglasses. There is a hint of Peter Sellers’ farcical Inspector Clouseau from the Pink Panther movies here— secrecy that was hardly warranted and a disguise that would not have fooled anyone who was even vaguely familiar with the Kissinger visage.

The convulsive laughter in Beijing must have been a sight to see. Here were hard-boiled revolutionaries, who had fought and survived a cruel civil war and a war against Japan, being asked to play amateur cloak- and-dagger with the naïfs, Nixon and Kissinger. Is it any wonder that the meetings with Kissinger were marked by a touch of condescension on the part of Mao and Zhou? While Nixon and Kissinger were full of vanity and desperate to leave their mark in history, Mao and Zhou were comfortable in their own skins and had already taken their places in history. The meetings were not of equals: the Americans kowtowed, and the Chinese knew it. Kissinger seems to have been overawed and so desperate to make the opening that he exceeded his brief. For instance, according to John Pomfret, ‘He [Kissinger] assured Zhou that whether or not China pursued peaceful unification with Taiwan, “We [the US] will continue in the direction which I indicated”—which meant that the US would withdraw recognition of Taiwan and establish ties with China.’

Nixon and Kissinger certainly made the breakthrough—and more— with Beijing that the Kennedy administration had hoped to curate. Yet, the roots of the China opening go back to the assassinated president and his team. Neither Nixon nor Kissinger were ever generous with their praise of others. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that too much credit has been given to Nixon–Kissinger and particularly to Kissinger, given that Nixon had conceptualized the opening as early as 1967.

Also read: Don’t burden Delhi-Washington ties with Afghanistan, or issues like democracy under Modi

The world after the Kissinger visit

The choreography around Kissinger’s trip may have been ludicrous, but the purpose was serious as were the consequences. It was correct to bring China out of the cold and into international order: one billion people had to be recognized and integrated. The alliance against the Soviets was less understandable. If Washington and Beijing had read US diplomat George Kennan’s ‘Sources of Soviet Conduct’ more carefully or taken more seriously the young Russian dissident Andre Amalrik’s Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984? (published in 1970), they would have seen that they were confronting an increasingly hollow empire that was not far from self-destruction. Or perhaps the Chinese knew the extent of Soviet infirmities but played on the credulity and greed of the Americans to further their own project—which was more about accessing US investment/technology than it was about forging a common front against Moscow. After all, Beijing could have hardly failed to notice that only those countries that befriended the US and accessed its capital and knowhow achieved rapid, sustained economic growth: that was the story of East Asia from the 1950s onwards.

More than Nixon and Kissinger, it was Carter/Brzezinski, then Reagan/ George W. Bush Sr., and finally Bill Clinton that helped China on its extraordinary economic journey from 1979 to the present—which is why the Chinese accusation that the Americans have always tried to contain China’s rise is so laughably absurd. Beyond economic partners, the US and China became strategic partners. When the Soviets sent in their forces to save the Babrak Karmal government in Afghanistan in December 1979, the US and China with Pakistan deployed Islamic radicals to wear down the Red Army. Over the next decade, the US released high technology and weaponry to China to bolster the quasi-alliance. It granted most-favoured-nation (MFN) status to China, relaxed Cold War rules so that the US and its allies could sell advanced technology to Beijing, provided credits so that the Chinese could import US technology and approved World Bank loans.

The US also helped modernize China’s military equipment. Chinese students and tourists in the US and Americans visiting (and sometimes studying) in China grew dramatically. When Warren Christopher, Clinton’s secretary of state, rather timorously tried to raise the issue of human rights, Premier Li Peng, ‘the Butcher of Beijing’ (so named for his role during the Tiananmen Square protests), responded aggressively and cancelled the American diplomat’s meeting with Jiang Zemin, general secretary of the communist party. Predictably, China gave no ground, and yet in 2001 the Clinton administration went ahead to endorse China’s membership in the WTO. And the rest, as they say, is history—the history of China’s astonishing rise.

This excerpt from A New Cold War: Henry Kissinger and the Rise of China, Edited by Sanjaya Baru and Rahul Sharma, has been published with permission HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from A New Cold War: Henry Kissinger and the Rise of China, Edited by Sanjaya Baru and Rahul Sharma, has been published with permission HarperCollins India.