This was meant to be privileged communication between the army chief and the Prime Minister. But the next morning the Statesman carried a long exclusive ‘scoop’ by its political correspondent, saying that Thimayya had resigned and that his naval and air force counterparts may do the same. The headlines were big-banner and spread across the front page with the general’s photograph:

GEN. THIMAYYA DECIDES TO RESIGN

OTHER SERVICE CHIEFS MAY FOLLOW SUIT

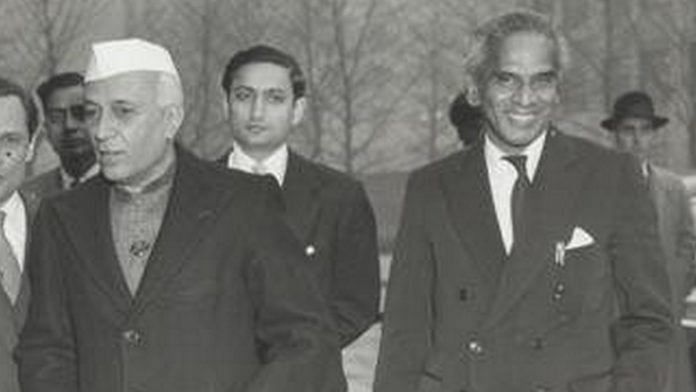

SERIOUS DIFFERENCES WITH MENON

The article went on to say that while differences had been simmering for quite some time, the immediate provocation for the general’s resignation was interference by Krishna Menon in a spate of top army appointments, which Thimayya resented. This was a sensational development, and with Parliament in session, it was but natural that MPs became highly agitated and demanded an explanation from Nehru. That coincidentally also happened to be the day when Nehru went to the airport to meet Ayub Khan, the President of Pakistan, who had decided to break journey at New Delhi airport while flying from Karachi to Dacca. Opposition MPs demanded an immediate statement from the Prime Minister, who somehow was able to buy time for a day on the grounds that he was tied up with the President of Pakistan.

As Krishna Menon’s opponents were sharpening their knives, Nehru received another letter from Thimayya on the morning of 1 September 1959:

Since I sent my letter of resignation to you I have had two talks with you and I have decided to take your advice and withdraw my resignation.

But the damage had been done, and from then on, Krishna Menon was a marked man. Two questions arise: Why did Thimayya write his letter of resignation? And how did its contents find their way into the columns of the Statesman in a matter of a few hours?

The second question about the source of the leak is more easily answered. For over five years, the Statesman had a military correspondent who wrote on defence matters from time to time.

This correspondent was no journalist really. He was none other than J.N. Chaudhuri, a top army officer whose articles would appear occasionally under the byline ‘By Our Military Correspondent’. He would become chief of the Indian Army in November 1962. My conclusion is that Chaudhuri was in the loop on Thimayya’s resignation and instead of writing the story himself, passed it on to the paper’s political correspondent. But there was to be no inquiry on how the leak had taken place. Chaudhuri would later admit in his autobiography to being the military correspondent of the Statesman from 1951 for a decade and confess that his ‘anonymity was very well kept’. But he was silent on whether he had official permission for this unusual arrangement and, of course, he said nothing on the Thimayya resignation episode.

Also read: India didn’t get its CDS in 1950s due to rift between Army chief & defence minister

What appears to have triggered Thimayya’s extreme reaction was this: In one of his frequent meetings with the Prime Minister, Nehru seems to have asked Thimayya how things were at the Ministry of Defence. Thimayya expressed his frustration at the way the minister was functioning. Nehru then promised Thimayya that he would speak to Krishna Menon about it, which he did. Thereafter, an infuriated Krishna Menon sent for Thimayya and accused him of going to the Prime Minister directly, bypassing the minister.

Thimayya’s defence that he had just responded to Nehru’s query did not cut much ice with Krishna Menon, who told him that the minister is the supreme authority. Stung by this, the proud and sensitive Thimayya decided to put in his papers. That the defence minister’s style of functioning created problems for a hierarchy-conscious armed-forces establishment was evident. That the defence minister’s strong leftist credentials often came into conflict with the way top members of this establishment, all educated in the UK, functioned was obvious.

That Thimayya had a larger than-life image with direct access to the Prime Minister, which was

not liked by his minister who believed in establishing the supremacy of the political class over the military top brass, was also clear. A coup had taken place the previous year in October 1958 in neighbouring Pakistan, and there was loose talk in the cocktail party circuit of whether India’s turn would be next. A naturally paranoid defence minister would have found all this sinister, even though the Times of India of 4 January 1959 carried this report:

No Possibility of Military ‘Coup’ in India

Ruling out the possibility of a military ‘coup’ in India, Mr. V.K. Krishna Menon, Defence Minister, said here today that ‘whosoever attempted such a thing would come to grief . . .’ Mr. Menon said:

‘We have a strong parliamentary system of Government. Our soldiers are well educated and disciplined. They do not meddle in politics.’ ‘In fact’, Mr. Menon added, ‘it is silly to think in terms of a military dictatorship’. ‘The people’, he said, ‘were conscious of their democratic rights and the prevailing social conditions widely varied from what led to military regime in other countries’ . . .

Also read: Bumbling Nehru, paranoid Menon, divided Army — stunning tales from India’s military history

In addition, Mountbatten had been pressing both Nehru and Krishna Menon to appoint a chief of defence staff (CDS) who would have overarching authority over the army, navy and air force, and had been suggesting Thimayya’s name for this post. Krishna Menon resented this lobbying and, in any case, was dead set against the idea of a CDS, thinking that it would give too much importance in policy to a single military man.

A month after the Thimayya resignation episode, the UK high commissioner in India, Malcolm Macdonald, met General Thimayya on 6 October 1959 and sent back a report of their long conversation, which was largely on the India–China border question. Towards the end, the topic of the minister of defence came up and Macdonald wrote:

General Thimayya said one of the great difficulties in all this business had been Mr. Krishna Menon’s zeal in representing the Pakistanis as the true enemies of India. Mr. Menon played up and often publicized as extremely unfriendly every small frontier trouble between the Pakistanis and Indians, invariably blaming the Pakistanis. The General did not know why the Minister did this. Perhaps it was because Mr. Menon wished to strengthen the case he had made (with popular effect for himself in India) against Pakistan over the Kashmir issue. Anyway, whatever the reason, the Minister of Defence insisted that India’s armed forces should be disposed on the assumption that an attack on India would be launched from Pakistan.

General Thimayya had often argued with him on this question, but never with success. Stimulated by one or two questions from me, the General said that Mr. Menon had no idea of how to deal with people, including officers and men in the armed forces. He tried to steamroller them into agreement with him on all matters; he was unscrupulous in his unfriendliness towards those who stood up to him; and he was cunning in the exploitation of those who were prepared to give way to him. He sometimes ordered posting, promotions and removal of officers according to his own whims . . . He observed that Mr. Menon must know how unpopular he is in India, and that he was perhaps trying deliberately to make himself the master of the armed forces so that he might one day have their support in the achievement of his political ambition to take Mr. Nehru’s place either after, or even before, Mr. Nehru’s withdrawal from public life.

Also read: V.K. Krishna Menon, the ‘evil genius’ behind the non-aligned movement

This was quite an extraordinary charge made by Thimayya to Macdonald—that Krishna Menon entertained dreams of staging a coup against Nehru. Had either Nehru or Krishna Menon known that Thimayya was talking like this, albeit privately, the general would have been asked to go. Macdonald continued:

The General told me that he had ‘bent over backwards’ to work successfully with Mr. Menon . . . But the Minister had been obstinate . . . and the situation had become more and more impossible. In the end he had felt it necessary to tell the Prime Minister, and to send in his resignation. The Prime Minister had pleaded with him to withdraw the resignation . . . In response to the very strong pleas by the Prime Minister and out of great respect for Mr. Nehru, the General had agreed to withdraw his resignation.

The General told me that after the news of his intended resignation was published he had received all sorts of messages of support. The Armed Forces were unitedly with him, and so were innumerable politicians . . . Some of Mr. Menon’s own colleagues in the Cabinet had privately expressed their support for the General . . .

That Thimayya opened up to Macdonald was highly unusual as, after all, the latter was the UK high commissioner, and the top army man was telling him every detail of what he had said to his Prime Minister and defence minister. Macdonald’s record of this conversation with Thimayya, buried in his archive at Durham University in the UK, does call into question the general’s judgement, even allowing for the fact that he felt he had been treated badly.

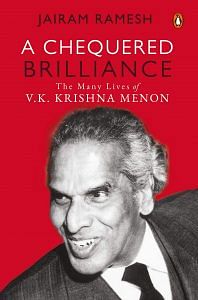

This excerpt from Jairam Ramesh’s A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Jairam Ramesh’s A Chequered Brilliance: The Many Lives of V.K. Krishna Menon has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

We must know the history of our country so that we can shape our future.

Historical facts must come to light. Past actions shape the future decisions. Here CAB or employment is not the topic of discussion!

Krishna Menon was primarily responsible for isolating India from the comity of nations. Highly egoistic and arrogant, he was anti – West to cover up his nonparticipation in the liberation struggle. He was a stooge of the Russians. His negligence in not keeping the army ready for action was exposed when the Chinese defeated the Indian army and occupied large swathes of Indian territories. Nehru finally realised the mistake of appointing as defence minister and fired him.

Does this news item has any relevance to day’s politics . Even the youth is protesting against CAA which is equally irrelevant to them instead of asking for jobs and employment.

Every one wonders why we dint have a CDS before. We had men in Uniform reporting to Civilian President who is the supreme commander. I dont know the current reporting structure of defence chiefs to the newly created CDS. Pakistan Bangladesh srilanka Myanmar or even for that matter Thailand had suffered. If this position is that of co ordination within the services it might be useful as we are in a much more matured environment than 50s and 60s.

We need discuss history thread bare. So that we do repeat costly mistakes which otherwise can be avoided.