One of my core duties as Bowles’ personal assistant [in India] was to take charge of the schedule for visitors who were important to Steb—like Duke Ellington, Pete Seeger, those sorts of people—and use their presence to put on programs that would appeal to Indians. My routine in those days was to wake up early and skim the morning papers. I would go through the seven or eight English-language papers quickly, noting anything that should be called to the attention of the Ambassador.

I was up especially early on November 23rd—it was Dagmar’s birthday—and found the papers face down on our doorstep. After arranging birthday cards around Dagmar’s place at the breakfast table I turned over one of the papers and was stunned.

In stark black print: Kennedy Assassinated.

My first thought was that someone was pranking me— a sick joke. One by one I turned over each of the papers.

I could not believe what I was seeing—only the untimely death of an immediate relative could shock me more. I read the headlines again. They were as simple as they were unbelievable. A part of me just couldn’t process it. I stood absolutely still for what seemed like a long time as a myriad of implications ran through my mind.

I needed to talk to someone. To wake Dagmar, to call Doug Bennet, to do something.

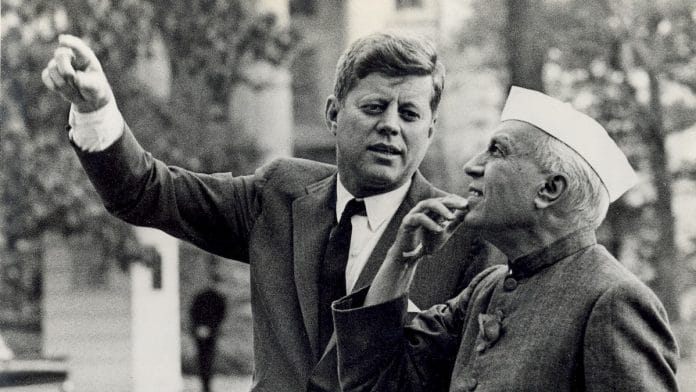

Bowles, at the time back in Washington, had been scheduled to meet President Kennedy in the Oval Office November 25th to discuss the possibility of increasing military aid to the Indians in light of recent hostilities between them and the Chinese. Bowles believed such assistance would be a way of furthering our interest—and our relationship—with India and thought Kennedy was amenable to the idea. But now Kennedy was dead. What would happen to this opportunity?

Also read: India’s misplaced priorities, shoddy planning & complacency led to 1962 war

Bowles was eager to put the case for increased military assistance to India before President Kennedy. Tensions between India and China remained high after the armed conflict in late 1962 along the ill-defined and disputed bother between the two Asian nations.

While the United States had responded to Nehru’s request for assistance it did so in a restrained fashion with communications equipment and small arms, mindful that our ally, Pakistan, argued that any weaponry we gave to India could and would likely be used against them. Bowles took the long view—that over time India would provide a democratic counterweight to the influence of China. Indeed that had been the theme of one of his lectures at Delhi University.

A delegation of US Senators led by Gale Magee had visited to determine whether our equipment had been useful to, and appropriately deployed, by the India forces in the mountains. In fact, the visitors traveled to Leh in Ladakh to meet with senior Indian officers there. They had concluded that the material that the United States had provided was indeed welcome. But they also felt that more substantial support was justified.

But Kennedy’s death brought the curtain down on our short-lived military supply mission to India. Bowles turned his attention to advocating for the importance of helping India’s economic development, arguing that only a strong and successful India could balance the ambitions of the Chinese.

Also read: Britain had become paranoid of India-US friendship. Nehru’s letter to Roosevelt didn’t help

A week later I wrote in my journal, recalling that day: “Logic had deserted history in one cheap and unreasonable and brutal and all too human act.”

As soon as I could think clearly I called the Embassy. The Marine Guard picked up the phone, and I asked him about the headlines.

“It’s true,” he told me.

I told him I’d be right in.

In some respects the State Department is at its best when an entirely unthinkable act like the Kennedy assassination occurs. They have a drill for everything; they know what to do at a time of crisis. By the time I arrived at the Embassy the flag was already at half-mast and the Marine Guards had been issued black armbands. A conversation was underway—which I joined immediately—about the condolence book that would be placed in front of the Embassy where people from all walks of life could convey their sympathies. A year and a half earlier, Jacqueline Kennedy had come to India to dedicate the new Embassy and Residence and had received an overwhelming welcome. There would be an outpouring of sympathy. We needed to find ways to manage it.

Still, there was no getting over the shock of it. Lyndon Johnson was president. How could a young person like Kennedy be dead? Who did this? What kind of madness was this? We lived by the newspapers and news ticker, talked in hushed voices and prayed for the best—especially that Lyndon Johnson would fight for the causes Kennedy had enjoined: civil right, peace, and global development. Death cast Kennedy’s shadow bigger than it had been in life and the closeness of the family (which had been much maligned during the election campaign) now made the loss seem somehow more acute, more palpable, more intimate.

We tend to be cynical about our politicians. But the youth, energy and courage of Kennedy, his graceful and beautiful family, had seemed somehow to rise above that. In the words of his brother Teddy, President Kennedy sparked “a dream that would never die.”

In the midst of the trappings of grief, Pete Seeger arrived. Because of the President’s death all public events we had planned were cancelled. But he, his wife Toshi, and their son Dan spent four days inNew Delhi anyway. They grieved with the rest of us.

The overlay of my coming to terms with Kennedy’s death was trying to entertain Pete and Toshi Seeger without totally depressing everyone. Pete’s response to the tragedy was that he wanted to sing, believing that music would provide an emotional outlet for people.

That was probably true, I told him, but protocol dictated that to honor the President’s memory we had to observe a ten day period of mourning during which there could be no official events. Pete did sing, though. In our house. I have a vivid memory of him going upstairs each evening to sing Dan to sleep.

Finally, on Pete’s last day Steb and I agreed that we had to find a way for him to perform. “Maybe,” I suggested, “we could do something informal.”

We took Pete to an elementary school near the Embassy where he sat and sang to and with the children. He sang “itsy-bitsy spider” and a whole set of children’s songs. The kids loved it. He loved it.

That evening, we gathered a few friends to honor John Kennedy. One of Prime Minister Nehru’s aides, a talented traditional Hindi singer, joined Pete in our living room, along with perhaps a dozen people including Steb—Chet was still back in Washington—Toshi and Dagmar. Pete and our Indian friend traded songs back and forth for perhaps two hours.

It was intensely sad and intensely uplifting—a remarkable moment.

An extract from the forthcoming book by American former Ambassador Richard Celeste, ‘Life in American Politics & Diplomatic Years in India: An Unvarnished Account’ being published by Har-Anand Publications, New Delhi.

An extract from the forthcoming book by American former Ambassador Richard Celeste, ‘Life in American Politics & Diplomatic Years in India: An Unvarnished Account’ being published by Har-Anand Publications, New Delhi.