More conversation followed on the intellectual vision with which JNU was set up in 1969. The idea of the new university was to explore Indian society through interdisciplinary studies and discussion. In 1971, the Centre for Historical Studies, one of the oldest centres in the School of Social Sciences in JNU, launched its postgraduate studies programme guided by a team that included Romila, S. Gopal and Bipan Chandra. The programme was a departure from the usual conventional takes on the study of history. Simply put, it did not view the past as ‘another country’; instead, the past was the subject of study because it shaped the present. The Centre also pioneered a course of study of contemporary history.

Githa Hariharan: To continue with the idea of the university in general, but also JNU in particular … you have been associated with JNU from the beginning—would you give us an idea of what this vision was? Would you call it Nehru’s vision?

Romila Thapar: The vision really was not so much Nehru’s—we must remember that the university came into existence after he died. It was originally supposed to be called Raisina University, after the village where the Viceregal Lodge was built. Then somebody had a bright idea: ‘Why not name it after the first prime minister?’ So it was called the Nehru University.

The JNU vision actually developed through the 1960s among academics and intellectuals in India. They thought, ‘We are an independent country, we have an identity.’ And they asked themselves, ‘What kind of society do we want to build?’ The response was this vision—the university had to help in understanding both the identity of India, and the kind of society we wanted.

When I joined JNU at the end of 1970, I think I may have been just the third professor to join. We did not really start functioning until 1971, actually late 1971. The vice-chancellor then was not an academic but he was a man of much vision, now that I look back on it.He told us, ‘I want a university which is not a replica of any of the existing Indian universities. I want a university that will tackle new ideas, and explore knowledge. And I want it to be interdisciplinary.’ This was the mandate we were given. I remember how we worked on this mandate in the History Centre since we too agreed with it and wanted to make it possible. There were three of us first, then we recruited a few people about three or four months down the line, so that we were about ten of us. And we brainstormed day and night, day and night, thinking of new courses; the kinds of courses that would help us explore Indian society.

GH: Academics was not something disconnected from the rest of teaching and learning.

RT: Precisely. Academics was not disconnected. What we were doing had a context. It was not as if I was dealing with something abstract in ancient Indian history. I had to tell myself that the past is not another country. The past is still with us. And what is it that we are doing with the past? How are we relating it to the present? This was a major aspect of our exercise.

The other aspect we were very conscious of was the fact that since we were doing new courses, they had to be extremely analytical. And so we began with one of the courses that we had invented, ‘Historical Method’, which did not exist in any university at that time. The course was intended to explain to students that there is a method, that the social sciences have a method. History is not just a story, it is not a narrative for which you read six books, string the events together and say, ‘This happened, then this, then that.’ There is an explanation for why things happened, why people became the kind of people they were, and the kinds of roles they played. So the basics of social sciences involve some questions: What is your evidence? How reliable is your evidence? What causal links are you making between your bits of evidence? What is this leading you to? Is your eventual argument based on logic and reasoning? These were fundamental issues.

GH: Romila, you have given us a clear idea of the academic, scholarly, intellectual base of what a university project is. I want to ask you about the extension of this base. Surely, a young person goes to college or university for academic study, but also life in general, including life as a citizen. Learning to be a citizen is intimately tied up with the vision you have for how academics will be conducted. I refer to this because I want us to talk about JNU’s ‘tradition’ of questioning both within the classroom, within the context of academics, as well as within the context of society.

RT: That was a remarkable thing. It was remarkable both for me and the students who came to us. I had taught in Delhi University, and I had taught a bit in London University before that. On the whole, my experience was that the teacher came into the class and gave you whatever lecture they wanted to. You took your notes and you went off, and did a little bit of reading. That was it.

What we began doing in JNU was quite different. For example, in my first lecture I said to the students, ‘A lecture is not a monologue. It is a dialogue between you and me. I will say things that you may not understand very fully, or that you may disagree with. In which case, please stop me, and we can have a discussion.’

For the first three weeks, there was dead silence. I would talk; they would listen and take notes. Then suddenly one day, a student raised her hand and said, ‘I don’t think I quite agree with that. Could you explain it?’ And we had a lovely discussion. After that the class changed. The best thing about a lot of the JNU lectures was that there were really ‘discussion lectures’.

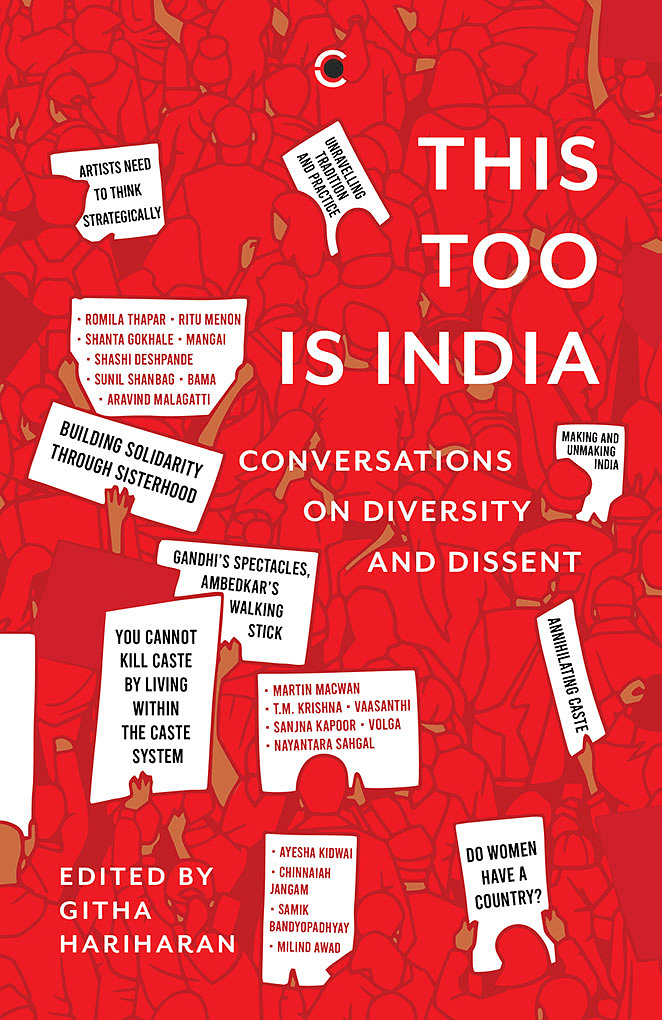

This excerpt from This Too Is India: Conversations on Diversity and Dissent by Githa Hariharan has been published with permission from Westland Books.

This excerpt from This Too Is India: Conversations on Diversity and Dissent by Githa Hariharan has been published with permission from Westland Books.