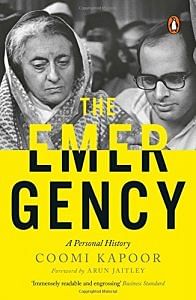

Coomi Kapoor’s book The Emergency explores the complicated relationship between Jayaprakash Narayan and Indira Gandhi who widely differed in their opinions.

The failure of Jayaprakash Narayan and Indira Gandhi to reach any understanding, despite the old and close association between JP and Mrs Gandhi’s family, was because of their widely differing perceptions. To JP, his campaign was a mass movement against growing corruption in public life, and increasingly authoritarian tendencies in government at both the Centre and state levels, with frequent suppression of civil liberties.

JP believed that, far from creating an atmosphere of anarchy and violence, his movement provided a peaceful outlet for the anger and frustration of the youth, in particular of students. But instead of being responsive to their unrest, the government set about crushing the movement with a heavy, repressive hand. This was because Mrs Gandhi viewed JP’s movement as aimed personally at her. She insisted that JP was encouraging anarchy, preventing the government from functioning, and trying, through a minority opposition, to submerge the voice of the majority. ‘Does he want to be a saint or a martyr? Why does he refuse to accept that he has never ceased to be a politician and desires to be the prime minister?’ she once complained to Pupul Jayakar. Historian Bipan Chandra described JP’s call for Total Revolution as ‘hazy, naïve and unrealistic thinking’ and his demands too general to amount to concrete politics.

Indira Gandhi’s dismissive opinion notwithstanding, JP was a formidable opponent, with a moral authority that Indira Gandhi lacked. He was an icon of the freedom struggle, a hero of the 1942 Quit India movement who had daringly escaped from Hazaribagh jail. When he was finally rearrested by the British he was released a full year after the other political prisoners. Before he joined the freedom movement, JP had been a student in the USA for seven years and had impressed his teachers with his scholarship and keen mind. On his return to India he was encouraged to join the Congress by Pandit Nehru. JP used to call Panditji ‘bhai’. The friendship extended to the two wives, Prabhavati and Kamala, who corresponded with each other regularly. It was a remarkably intimate exchange of letters between the two women.

After Independence, JP’s moral stature grew since he was one of the rare senior Congress leaders who had declined to accept political office. His revolutionary fervour had first taken him to Marxism and then, through the national freedom movement, to democratic socialism. When the socialists separated from the Congress in 1948 to form a separate party, he joined them. During that period, when JP was in the Praja Socialist Party, he was attracted to Vinoba Bhave’s Bhoodan movement, where donated land was collected for distributing to the landless. By 1957 JP had resigned from party politics to devote all his time to the Sarvodaya movement, which practised social work based on the principles and values preached by Mahatma Gandhi. But, as JP noted in the Sarvodaya Sammelan of 1961, not being in any political party did not mean ‘we are not concerned about what is happening in the country in the political field’. He subsequently directed his energies towards trying to settle conflicts in Nagaland and Kashmir, and later in Bangladesh.

JP had a soft spot for Indira Gandhi as she was Nehru and Kamala’s daughter. He congratulated her warmly when she was elected PM in 1966. From time to time he supported some of the government’s programmes. In 1969, however, he was unhappy with her conduct in the presidential election. And he said so frankly in a letter to Mrs Gandhi in 1971, when he congratulated her on her sweeping electoral victory: ‘I did not like your conduct at the time of the presidential election though I am aware that at that time it was politically a question of life and death for you. Now that you have been given uncontested power my prayer to God is that he may keep your thinking pure.’ Cut to the quick, Mrs Gandhi wrote back haughtily, ‘How little do you know or understand me. I have never bothered about political or any other identity for myself. At that time the question was not of my future but that of the Congress party and therefore of the country.’

Excerpted with permission from Penguin India

Excerpted with permission from Penguin India