The conflict in Kashmir intensified after 1989, resulting in a political and humanitarian disaster. Thousands were killed, and many more were injured; livelihoods were lost and homes destroyed. Many vanished as ‘enforced disappearances’. The Kashmiri Pandit community, the largest religious minority in the valley, was forced into an exodus.

Additionally, the insurgency had a profound impact on the psychological, economic, and social aspects of life in the state, severely hampering them. Existence was reduced to ‘bare life’, a term used by Italian Philosopher, Giorgio Agamben to describe a condition in which individuals are reduced to their mere biological existence, stripped of any legal or social protections.

Downtown, like the rest of Kashmir, was completely transformed by the jolting political and socio-cultural changes that took place in the valley within a mere few years from 1989, leaving those who had seen normalcy in a state of crippling disbelief and ensnaring the coming generations in lifelong trauma about their humanity and political existence.

To understand the scale of conflict and understand its impact on the lives of Kashmiris, Downtown Srinagar emerges as the obvious ground zero. Everything started from there. The first show of the gun in public, the proclamation of Kashmir’s revolt through the tehreek, the establishment of the separatist leadership, the crumbling of state order, the euphoric crowds waiting for azaadi to arrive, and the coffins of protestors for whom death arrived at point-blank ranges on the path to freedom—all unfolded in the streets of Downtown.

The period that marked the build-up and peak of the insurgency movement in Kashmir is remembered as one of mass euphoria in collective memory, and the streets of Downtown are replete with accounts of that brief phase of ecstasy. In the earlier years, marches of celebrations and protests were held across the city. People came with decorative buntings, some burst crackers, and some distributed baadam mithae amongst the crowds.

Experts attribute this mass euphoria to a string of significant geopolitical events, including the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the reunification of Germany. In each of these events, public mobilization against imperialist powers were considered to be crucial for their success. Emboldened by these global milestones, the idea of freedom seemed within reach, and people prepared themselves to receive ‘phoolon wali azaadi (the glorious freedom)’, as it was highly rumoured to arrive in a matter of days.

Even within this euphoric trance, it remained unclear what azaadi meant for different people. For some, it was self-determination; for some, it was a merger with Pakistan; and for some, it meant freedom from Indian rule. Nevertheless, people waited for it. In some areas, people had started symbolically burning Indian currency to mark the end of old systems and indicate the arrival of new ones. In other areas, people had stopped stocking up on food to make space for produce from the other side of the border.

Also read: Kashmiris have nicknames for all political leaders—‘If we don’t laugh, how can we live?’

Downtown had, supposedly, zones of independence which were safe zones for local and foreign militants to hide. Militants trained in Pakistan and different locations in Kashmir would make appearances at public processions, chant anti-state and pro-freedom slogans, flash their Kalashnikovs, and receive heroic welcomes. The movement reached its pinnacle in 1989, during the kidnapping of Rubaiya Sayeed, the daughter of the then union home minister, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, and the subsequent release of the militants from the JKLF by the state.

Founded in 1976, the JKLF was a militant separatist organization that was active until 1996. Operating as an armed political separatist group in both the Indian- and Pakistani-administered territories of Kashmir, JKLF engaged in various violent activities, including throwing bombs, organizing kidnappings, and conducting targeted killings, particularly during the insurgency years of 1989 and 1990.

As the state government under National Conference and the central government under the National Front coalition, comprising the Janata Dal party, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the Left Front, yielded to pressure, the militancy movement received a boost. Even those in the valley who had been sceptical of the impact of the resistance movement were impressed as they watched the state apparatus crumble.

The momentum gained by the movement in its initial years was swiftly countered by the state’s aggressive retaliation. As weapons freely circulated in the market, new militant groups frequently sprang up, each with its own definition of freedom and set of guidelines for civilians to follow. The entry of state-backed Ikhwanis, pro-government militias, added another layer of complexity to the indigenous militancy movement.

By 1995, the movement had started showing signs of waning, partly due to the state’s stringent measures and partly due to the internal discord among the various groups. With too many factions, everyone had a gun, and people started using the movement to fight their petty personal wars. While the movement began as a centralized rebellion spearheaded by JKLF, it soon saw the participation of more radical outfits like Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, Allah Tigers, etc., who began pushing for stricter interpretation of Islam.

These outfits openly criticized the Sufi practices prevalent in the valley, such as the tradition of visiting shrines, demanding that Muslim women wear the burkha and Hindu women wear tikas so that their religion was publicly identifiable, and threatened against screening films in theatres. At the same time, security forces intensified their raids to locate hidden militants, leading Kashmir to a point where all civilians were viewed with suspicion. The line between a militant with a gun and a protester with a slogan started disappearing. Both were met with the same bullet.

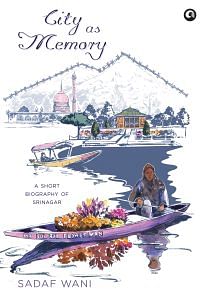

This excerpt from Sadaf Wani’s ‘City as Memory: A Short Biography of Srinagar ’, has been published with permission from the Aleph Book Company.

This excerpt from Sadaf Wani’s ‘City as Memory: A Short Biography of Srinagar ’, has been published with permission from the Aleph Book Company.