It was well past midnight and they were still far away from Saharsa. The group of thirty labourers, split into three teams, moved towards the Garhmukteshwar Ganga from different directions. After cycling for ten hours through the day and getting beaten up by the cops, they now moved stealthily to avoid attracting attention.

After walking for over three hours, crossing a jungle and then fields, Ritesh’s group wanted to rest for a bit. Krishna, in fact, was ready to sleep for an hour. But Ritesh announced that anyone stopping for a break would be left behind by the others—the fear of the police was still very real. His threat had the desired effect. Everyone kept moving because no one wanted to be left behind, alone in the dead of night.

Soon the band of seven reached a field that lay between the jungle and Balwapur village, where Ritesh decided it was safe to rest. Their bicycles scattered around them, they all lay down, clutching the small bundles of food and stuff they were carrying back home. The jungle was alive with the shrill cry of crickets and they could hear the sound of the river flowing nearby. A stray gust of wind occasionally caressed their exhausted bodies. The mosquitoes were relentless, but the men couldn’t have cared less. They were so tired that opening their eyes felt like lifting a ton of weight.

Ritesh’s phone started ringing. It was the alarm he had set for 4 a.m. He groggily tried to pull the mobile out of his shirt pocket but didn’t have the energy. Penetrating the stillness of the jungle, the alarm rang on as Ritesh slipped into a deep slumber. The labourers lay silent like corpses. Within half an hour the alarm went off again and Ram Babu, who was resting his head on a mound of mud, opened his eyes and gently patted Ritesh awake.

Ritesh awoke with a start, looked at his mobile, it was 4.30 now, and almost screamed in horror. Then he ran to each one and fibbed about the time.

Now, Ram Babu asked the main question: ‘What do we do next?’

No one had an answer until Ritesh said, ‘If the police won’t let us go by road, then we’ll get into the river and carry our cycles across.’

Also read: ‘Will take care of you’: States plead with migrant workers as Covid curbs spark fresh exodus

Twenty-eight-year-old Krishna, terrified at the prospect of a mass drowning, saw the faces of his old parents and four children swim in front of him. He had to live so that he could carry on supporting his family of eight. The responsibilities he now carried stopped him from doing anything risky, including crossing the Ganga with his cycle. Then twenty-three-year-old Sonu Kumar said, ‘Why not? When there is a flood in the village and the water level rises by 10 feet, don’t we carry our luggage and swim until we find secure ground?’

‘Sonu is right. Let’s go,’ said Ritesh, but Krishna stopped them.

‘This is Ganga ji. The currents are swift. Has the police beaten the common sense out of you all?’

‘Should we go back to Ghaziabad?’ asked Ritesh. ‘The landlord won’t let us in. If we stay here, the police will not let us survive. What choice do we have, Krishna? If we have to die, let’s drown in Ganga ji. At least we’ll attain moksha.’ As the group looked at Ritesh in shock, he said ‘I’m leaving. Those who want to come along raise your hands.’ Only Ram Babu and Sonu did. Then Mukesh made one last attempt at delaying the decision. ‘Let’s wait till daybreak Ritesh,’ he said.

‘Police brutality doesn’t bother about sunrise or sunset,’ retorted Ritesh.

‘It’s suicide,’said Ashish.‘At least you try and understand us, Ram Babu.’

If Ram Babu, the eldest, understood the extreme risk he could convince Ritesh to stop leading them all to an early death. But Ram Babu rarely, if ever, went against Ritesh. ‘We don’t have any other option now, Ashish,’ he said. ‘Let’s see how far we can move with our cycles. If we find it is impossible, we leave the cycles and cross the Ganga. We have to do something.’ Emboldened by Ram Babu’s assertion, Ritesh set off. Ram Babu and Sonu followed. The remaining four were convinced that in the next ten to fifteen minutes, their group of seven would be reduced to four.

‘Ritesh,’ yelled Krishna. ‘Stop, my friend. We’ll try and find another way.’ But Ritesh wouldn’t stop.

‘Mukesh, Ashish say something!’ pleaded Krishna.

Ritesh, Ram Babu and Sonu were already at the river’s edge, and bowing to the Ganga. Their foreheads touched the sand and when they raised their heads they were startled to see Krishna and their other companions in front of them.

‘Ritesh please let’s think of something else. Ram Babu, you are the eldest; what has happened to you? Please talk some sense into him,’ begged Krishna.

‘I may convince him, but how will I convince myself? Tell me?’ demanded Ram Babu.

‘I think the fishermen are awake.’ Krishna suddenly pointed to two people walking towards the river. Everybody turned to look.

‘Let’s go talk to them,’ he said. ‘Who knows, we may have some luck with them.’

Even Ritesh felt hopeful. The fishermen, now unfastening their boats, were startled to see seven strangers with bicycles suddenly appear in front of them.

Also read: ‘We’ll fall sick among family’: Migrant workers in Ahmedabad flock to catch trains back home

‘Yes, brother, what’s the problem?’ asked one.

‘Brother, we are going to Saharsa in Bihar and are coming from Ghaziabad,’ said Ritesh.

‘How are you here?’ asked the other fisherman.

‘The police beat us up mercilessly on the highway, so we decided to walk through the jungle and cross Ganga ji. Can you help us a little?’ The fishermen looked at each other, then the first one said, ‘You are right, the police is very strict and is resorting to violence at the slightest pretext.’

‘Please help us,’ begged Ritesh.

‘I told you just now, the police is flogging us too. Yesterday, his younger brother was taken to task and kept in the lock-up throughout the day,’ said the first fishermen, pointing to his partner. ‘Do you know what his fault was? He had helped three men with cycles to cross the Ganga.’

‘Please help us too, brother,’ pleaded Krishna.

‘I told you! The police is shoving lathis up our ass,’ the first fisherman said.

‘Look, you can take some money. Fifty or a hundred rupees each,’ said Krishna.

‘It’s not about money. It’s about police lathis. When they start beating us, who will come forward to take the blows?’ demanded the first fisherman.

‘We will, brother, don’t worry,’ said Ritesh earnestly, but the fishermen thought he was making fun of them.

‘You think it’s a joke?’ the second fisherman snapped.

‘No, brother, I mean it. Please just help us,’ begged Ritesh.

‘No way. We don’t want any trouble,’ replied the first fisherman.

Also read: I walked with India’s migrant labourers. More than angry, they are hurt with Modi

Realizing that the fishermen were truly terrified, and that talking to them would be waste of their time, Ritesh said, ‘No worries, brother. Sonu, let’s go.’ The group followed Ritesh to the river, but Krishna made one last attempt ‘Brother,’ he begged the fishermen, ‘please have mercy. Help us. We have to cover 1200 kilometres.’

‘No, brother, we can’t,’ replied the first fisherman firmly. ‘Don’t bother us the first thing in the morning.’

Then perhaps pitying them all, the second fisherman said, ‘Try and stop them. The water is 20-feet deep. You won’t even find their bodies when they drown.’

Running toward the river, Krishna yelled, ‘Ritesh, this gentleman says the water ahead is 20- to 30-feet deep.’ But Ritesh, Ram Babu and Sonu kept walking. The water had come up to their knees. Krishna yelled again, ‘Ram Babu, they are saying there are crocodiles in Ganga ji.’

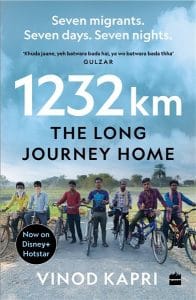

This excerpt from ‘1232 km: The Long Journey Home’ by Vinod Kapri has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from ‘1232 km: The Long Journey Home’ by Vinod Kapri has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.